The Terrorism Act has again proved to be much too broadly defined for comfort, writes Jo Glanville

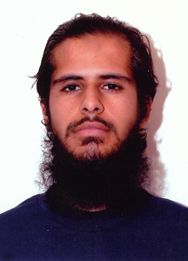

Aabid Khan, Sultan Muhammed and Hammad Munshi were all found guilty under the Terrorism Act this week. Between them they had what’s been described as a ‘terrorist library’: manuals on weapons, explosives and poisons, as well as video clips of mujahideen fighting and information about transport systems in the US and UK.

Their online conversations included discussing how to smuggle a sword through airport security. The dominant figure in the group — Aabid Khan — wrote chillingly of wanting to ‘cause trouble for the kuffar…cause fear and panic in their countries’ and aimed to recruit ‘a group of at least 12’. Khan received a 12-year sentence; Muhammad was sentenced to 10 years and Munshi — the youngest person to be convicted under the Terrorism Act — is still to receive his sentence.

Yet the main evidence against them was the documents in their possession. There does not appear to have been a plot. As far as the Crown Prosecution Service is concerned, there doesn’t have to be a plot. The men were prosecuted under Section 57 of the Terrorism Act 2000 — possessing an article for a purpose connected with terrorism. ‘The purpose of this legislation is to enable the police and the prosecuting authorities to act early against people who possess articles for a terrorist purpose, before a plan or conspiracy to commit a particular act has necessarily been formed.’

It’s worth comparing these convictions with a case that was quashed earlier this year in the Court of Appeal. A group of young men were convicted under the Section 57 of the Terrorism Act in similar circumstances (although less well connected than Aabid Khan to other extremists). They too had downloaded huge quantities of material and they too were excitedly discussing potentially violent ideas (the group also included a schoolboy). Yet the Court of Appeal found that possession of an article in itself was not an offence — what mattered was if was there an intention to use the material for terrorism.

It’s possible on this basis that there might be grounds for appeal.

The problem with this kind of terrorism prevention is that it constrains us all. There is no room for intellectual curiosity, for flirting with unfashionable ideology or even for engaging in serious research on the topic: Rizwaan Sabir and Hicham Yezza were reported to the police by their own university and detained for six days last May. Sabir had been studying extremism and had asked Yezza to print out a document for him.

Such is the culture of fear and confusion that he was not even safe to do his research in a centre of academic freedom. There can be no better example of how counter terrorism has pervaded our culture — and of the damage caused by such a broadly defined offence.