My song Beng Beng Beng was a simple, light-hearted love song coming from an African man’s perspective. I believe it was banned [in 1999] because there were other very political songs [on the album] that they didn’t want the radio stations to play. So banning Beng Beng Beng was like telling the journalists and radio stations, “Don’t touch this album”.

It was very popular in general, and everybody knew about it, but the radio stations never gave it airplay. I don’t think the lyrics were even offensive; it was less offensive than Let’s Talk about Sex, [by Salt N Pepa], but they played that for a long time on the radio stations. When they banned ‘Beng Beng Beng’ the stations were forced to stop playing anything sexual for a while.

httpv://www.youtube.com/watch?v=CKpTYLQ5K9w

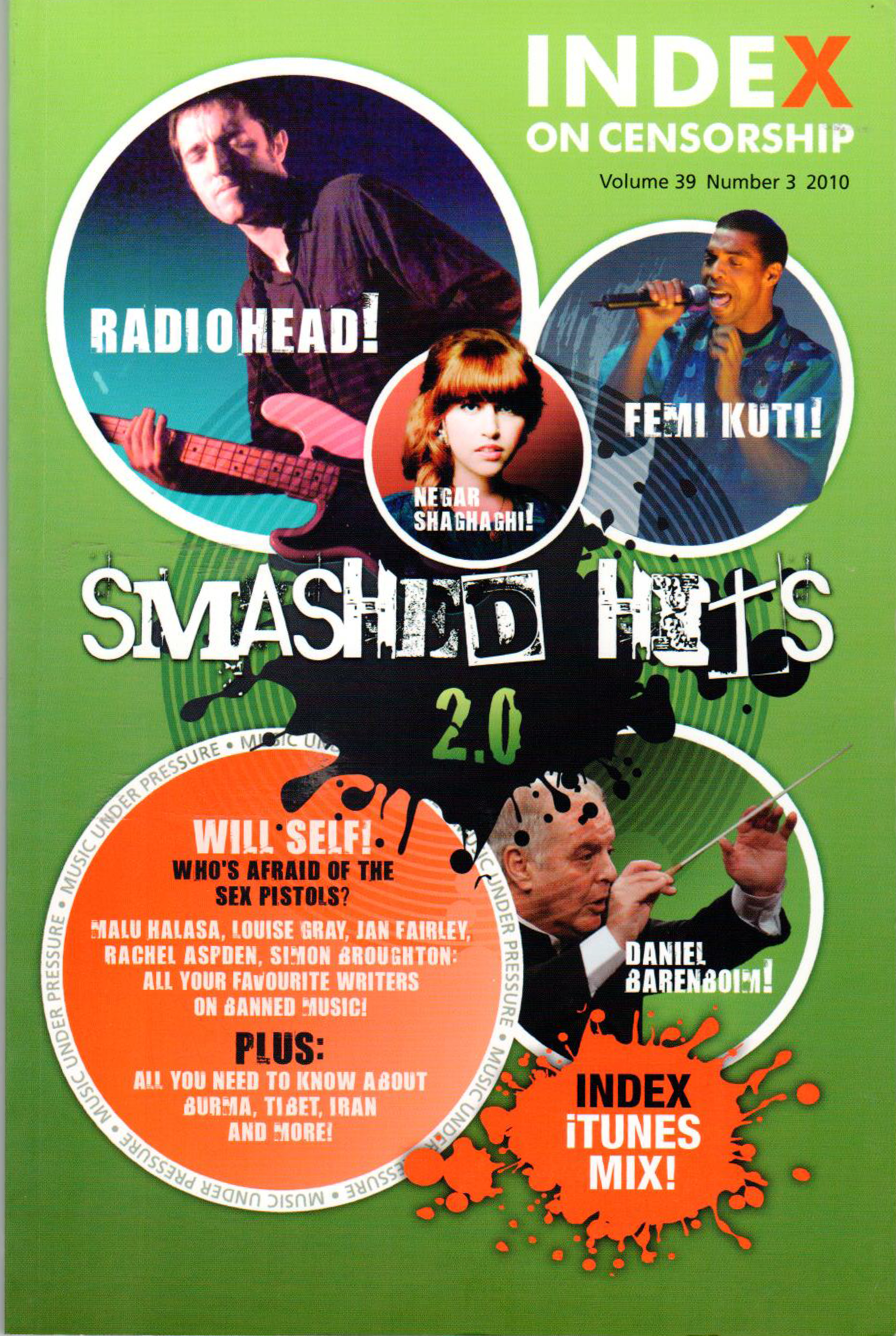

I was becoming too popular, too political, everybody was listening to me. People who didn’t even know about my father [Fela Kuti] were getting to know about me, then getting to know the whole story about my father. So I was getting to be a very big story.

My next album was angrier, more direct. The Shrine, my club in Lagos, was open and we played it live there, where it’s always full — we always have about 2,000 people. And they always try to close the club. The last time they tried there was so much international talk about it that they opened it after a week and a half. Everyone was outraged — and not just in Nigeria. There is more pressure coming from outside than inside. Now the government is trying to be accepted by the international community, they are trying to pretend they’re not corrupt, they pretend that everything is OK. Now, if somebody like me is shouting, “No, that’s wrong!” and they then ban my club, stop my music, then they are wrong, they are lying.

To read the rest of this article go to indexoncensorship/subscribe

To listen to contributors’ playlists go to indexoncensorship/music