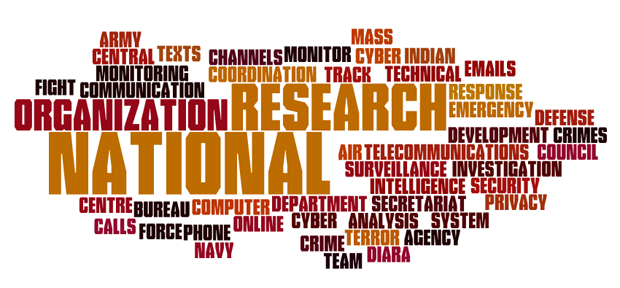

Two surveillance entities are being set up to monitor Indian citizens’ communications, Mahima Kaul writes

The first new system is the Central Monitoring System (CMS) that will be used by tax authorities and the National Investigation Agency to track phone calls, texts and emails to fight terror related crimes.

The second, the National Cyber Coordination Centre (NCCC), will be used by a host of intelligence agencies including the National Security Council Secretariat (NSCS), the Intelligence Bureau (IB), the Research and Analysis Wing (RAW), the Indian Computer Emergency Response Team (CERT-In), the National Technical Research Organization (NTRO), the Defence Research and Development Organisation (DRDO), the Army, Navy and Air Force, and the Department of Telecommunications to monitor all online activities to fight cyber crime.

As a result, there is increasing debate in India about how security concerns, through mass surveillance of all communication channels, are constantly coming head-to-head with the right to privacy. The reality is that governments do need to build some capacity to monitor different platforms as crime and terror increasingly exploit them. However, unless there are solid privacy safeguards, these mass surveillance systems can be misused with little recourse for the citizens. Protecting only the larger state, but not the individuals who make up that state is no way for a democratic country to function.

The reality is that banks, traffic, hospitals, nuclear and chemical plants and communication grids could be simultaneously attacked, rendering a country helpless. Technology plays such a central space in crime and terror that when Indian authorities were not able to decrypt BlackBerry technologies used by terrorists during the 2008 Mumbai attack, it ultimately led to the Indian government pressuring Research in Motion, the group that makes BlackBerry, to hand over its encryption keys to India.

The scope of cyber crime keeps changing and the government is looking to increase its capacity to respond to these challenges beyond existing frameworks like CERT-IN and cyber crime cells run by the police. Therefore, NCCC and CMS have been set up to help keep abreast of criminal online.

However, this gigantic effort, even if it is conducted with a view to national security, cannot be implemented outside regulatory frameworks. The Indian constitution provides fundamental rights to its citizens. Article 21 guarantees that no person shall be deprived of his life or personal liberty except according to procedure established by law. Logic dictates then, that clear policy and regulatory frameworks be set up to both protect the citizen’s right to privacy and also guide the security apparatus of the country.

To this end, the Information Technology Amendment Act, 2008, does allow for surveillance and data gathering. Section 69B of that act gives the government the authority to “monitor and collect traffic data or information through any computer resource for cyber security.”

However, security agencies have been questioned about spying on individuals without following proper procedure in the past. One the one hand, citizens are questioning the legal frameworks which have guided the creation of surveillance bodies like CMS, and on the other, the protection accorded to citizens.

India’s minister of state for Information Technology, Milind Deora, has stated that CMS is better for privacy, as it allows the state to directly intercept citizen’s communications, rather than relying on private operators.

However, legal expert Bhairav Acharya has argued that this position is disingenuous and incorrect, stating that by “bypassing private players to enable direct state access to private communications will preclude leaks and, thereby remove from public knowledge the fact of surveillance.”

In fact, it only reinforces the fact that citizens might never know when their personal information is being recorded and used, and why.

Privacy is at the forefront of this debate. India’s Planning Commission put together a “Group of Experts on Privacy” to produce recommendations on privacy protection and to ensure that the country’s privacy laws keep up the pace with laws drafted in other jurisdictions.

The report proposed that any legislation passed by Parliament be based on nine points, which include the concepts of notice, choice and consent, accountability and purpose limitation.

The government of India has now indicated that it will table a privacy law in the next session of Parliament. Even though the details are not yet public, think-tanks such as the Centre for Internet and Society have made a few guesses about what it could entail. They have concluded that privacy won’t be made a fundamental right, but citizens may be given a statutory right to privacy.

Privacy law is not just essential for preventing abuses. It is also needed for schemes that collect large amounts of personal data, such as India’s Unique Identification Number (UID) project. The UID is a large database of biometric data and other sensitive information, which could have a devastating effect if abused or leaked. To their credit, the Group of Experts on Privacy have advised the government to consider safeguards like informing citizens when their data is breached, changes in privacy policies, and requiring written consent from citizens before their data is shared with anyone.

Ultimately, India’s government should have had a privacy law in place well before it started rolling out surveillance agencies. The only way to move forward is to put measures in place to ensure that India’s surveillance system protects citizens rather than exploiting them.