From America to Azerbaijan, leaders have pledged themselves to a new era of openness and transparency. So why are whistleblowers and journalists still punished, asks Mike Harris

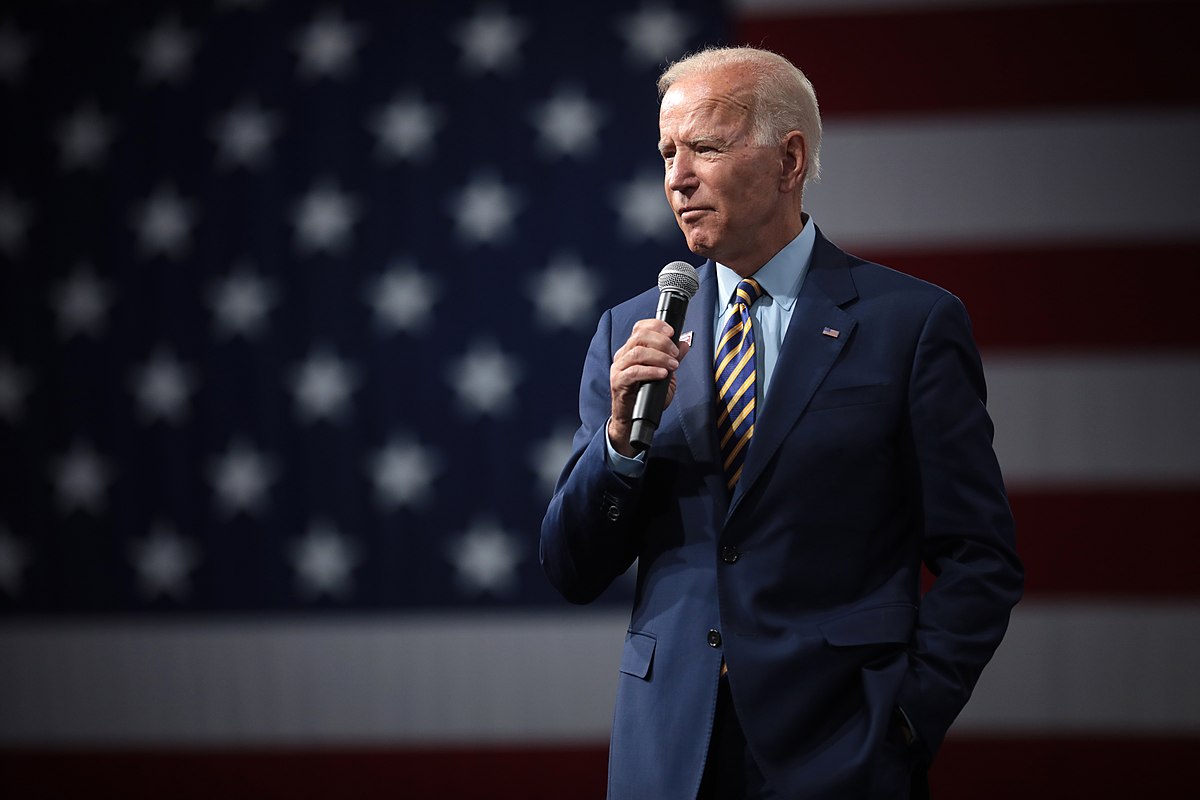

Is Barack Obama committed to transparency? (pic Gonçalo Silva/Demotix)

“My Administration is committed to creating an unprecedented level of openness in Government” –Barack Obama, 21 January 2009

Governments across the globe are making bold promises to embrace open government ushering in a new era of public service reform, undermining corruption and increasing citizen engagement — all underpinned by open data and transparency. In September 2011, the Open Government Partnership was launched when a number of founding governments (Brazil, Indonesia, Mexico, Norway, Philippines, South Africa, United Kingdom and the United States) endorsed an Open Government Declaration, and announced their country action plans. Since then an additional 47 governments have joined. The global G8 forum also made transparency a priority.

Open government should mean making government and public bodies more transparent, responsive and accountable so that citizens can hold these bodies to account, fight corruption and use technologies to make government more effective and accountable. In practice this requires government and public bodies to bring forward freedom of information legislation, let citizens get access to the huge data sets held by public bodies and make public bodies respond to questions from citizens and the media quicker and more thoroughly.

Unfortunately, it’s increasingly clear what governments feel open government isn’t about — it certainly isn’t about protecting whistleblowers, opening up the security services to scrutiny, or declassifying the huge amount of information marked as secret by governments.

The Open Government Declaration mention the watchdog role of the media and journalists in analysing information and exposing malfeasance and corruption.

Open government, while a noble aim, is overly focussed on opening up uncontroversial data sets and the method of distributing these data sets. As Evgeny Morozov points out in his recent book To Save Everything, Click Here, putting train timetables online, while useful, is not the same as giving citizens the data they can use to tackle corruption.

President Barack Obama made an early commitment to refound American government around openness and transparency. This in practice has meant very little. In February 2013, 49 NGOs and organisations wrote to the President calling for him to fulfill his Open Government obligations. Yet, the routine over-classification of information, demonstrated by the Wikileaks’ US embassy cable leak, shows a government unwilling to open itself up to scrutiny from the citizens who pay for its work. Obama’s record on freedom of information and state secrets is patchy at best. On whistleblowers, the Obama administration has been downright hostile. The attempted prosecution of Edward Snowden for whistleblowing shows the First Amendment protection for freedom of expression is being interpreted in a narrow manner. It’s depressing to see the official newspaper of China’s communist party take the moral high ground in an editorial noting all Snowden did was “blow the whistle on the US government’s violation of civil rights.”

Azerbaijan has endorsed the Open Government Declaration alongside the US. It has a law on the Right to Obtain Information which states that any person can submit a request for information (any facts, opinions, knowledge produced or acquired in fulfilling duties as specified by legislation or other legal act). Yet when journalists use this information they often come under attack.

Investigative journalist Khadija Ismayilova has used the Right to Obtain Information law to obtain documentation to expose corruption in Azerbaijan. In early 2012, shortly after Ismayilova published an expose of the business interests of the President Aliyev’s daughter, she received a threat telling her to stop her investigations. Ismayilova refused to back down. The next week a video of her having sex with a man was distributed on the internet. Ismayilova, who is unmarried, feared for her safety in Azerbaijan which remains a deeply conservative country.

Throughout Africa, Open Government is also a buzz phrase that has been endorsed by significant institutions. The African Development Bank has launched the “Open Data for Africa” initiative which aims to promote statistical development in Africa as a basis for creating effective development policies to reduce poverty. The African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights have also prepared a “Model Law on Access to Information for Africa”. Nation states are also on paper embracing the Open Government concept with Rwanda and Kenya two examples of states bringing forward legislation to this end.

In March 2013, Rwanda became the 11th African country to adopt a freedom of information law. The law also applies to private organisations where there is a public interest and their main activities relate to human rights and freedom. The government claims its objective was to promote Open Governance and hold public authorities to greater scrutiny. However, the law includes broad exemptions where access to information may be restricted in relation to national security, the administration of justice and for trade secrets.

In Kenya, the government launched its Open Data Initiative (KODI) in July 2011. It makes government data such as national census data, government expenditure, parliamentary proceedings and public service locations, open and accessible to people in Kenya. While Kenya has publicly backed Open Government, the legal framework, in particular the Communications (Amendment) Act 2008, provides for heavy fines and prison sentences alongside granting the state the power to raid media houses and interfere in the content of television broadcasts. The Kenyan Union of Journalists condemned the Act claiming it would “emasculate” journalism.

The publication of US State Department cables by Wikileaks demonstrated how the urge to over-classify documents is present even in established democracies. Open Government will only be as good as the data that is released. If Open Government is little more than a public commitment to put train timetables or the location of hospitals online, then it will fail to achieve the aspirations of the Open Government Declaration to tackle corruption, bring citizens closer to decisions or make public services more responsive. Open Government also has to recognise the importance of the media in processing and digesting the data sets and information that governments publish. Without analysis open data sets are just lines of numbers and letters. If the media is not free to do the analysis, or risks reprisals for doing so, Open Government will continue to fail to live up to its promise.

Mike Harris is head of advocacy at Index on Censorship @mjrharris