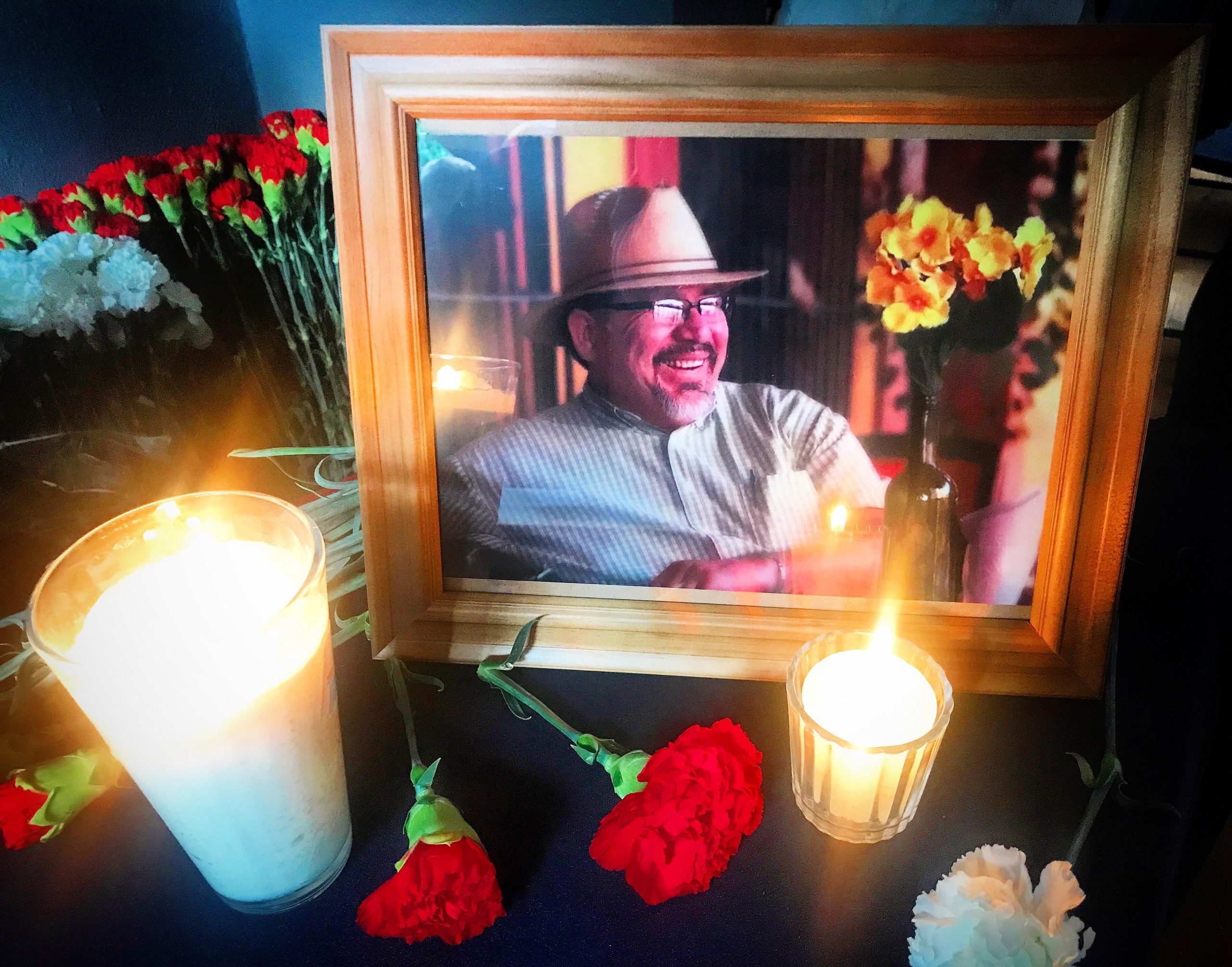

Grafitti of Tommie Smith, John Carlos and Peter Norman showing solidarity for the civil rights movement at the Mexico City Olympics in 1968 (Image: Newtown graffiti/Wikimedia Commons)

Athletes preparing to head off to Sochi Winter Olympics in February, have been reminded that they are barred from making political statements during the games.

”We will give the background of the Rule 50, explaining the interpretation of the Rule 50 to make the athletes aware and to assure them that the athletes will be protected,” said IOC President Thomas Bach in an interview earlier this week. Rule 50 stipulates that ”No kind of demonstration or political, religious or racial propaganda is permitted in any Olympic sites, venues or other areas.” Failure to comply could, at worst, mean expulsion for the athlete in question.

Political expression is certainly a hot topic at Sochi 2014. The games continue to be marred by widespread, international criticism of Russia’s human — and particularly LGBT– rights record. The outrage has especially been directed at the country’s recently implemented, draconian anti-gay law. Put place to “protect children”, it bans “gay propaganda”. This vague terminology could technically include anything from a ten meter rainbow flag to a tiny rainbow pin, and there have already been arrests under the new legislation.

The confusion continued as the world wondered how this might impact LGBT athletes and spectators, or those wishing to show solidarity with them. Russian authorities have for instance warned of possible fines for visitors displaying “gay propaganda”. Could this put the Germans, with their colourful official gear, in the firing line? (Disclaimer: team Germany has denied that the outfits were designed as a protest.)

On the other hand, Russian president Vladimir Putin has promised there will be no discrimination at the Olympics, and IOC Chief Jaques Rogge, has said they “have received strong written reassurances from Russia that everyone will be welcome in Sochi regardless of their sexual orientation.”

On top of this, the IOC also recently announced that there will be designated “protest zones” in Sochi, for “people who want to express their opinion or want to demonstrate for or against something,” according to Bach. Where these would be located, or exactly how they would work, was not explained.

But while the legal situation in Russia adds another level of uncertainty and confusion regarding free, political expression for athletes, rule 50 has banned it for years. And for years, athletes have taken a stand anyway.

By far the most famous example came during the 1968 Olympics in Mexico City — American sprinters Tommie Smith and John Carlos, on the podium, black gloved fists raised in solidarity with the ongoing American civil rights movement. The third man on the podium, Australian Peter Norman, showed his support by wearing a badge for the Olympic Project for Human Rights. All three men faced criticism at the time, but the image today stands out as one of the most iconic and powerful pieces of Olympic history.

However, the history of Olympians and political protest goes further back than that. An early example is the refusal of American shotputter Ralph Rose to dip the flag to King Edward VII at the 1908 games in London. It us unknown exactly why he did it, but one theory is that it was an act of solidarity for Irish athletes who had to compete under the British flag, as Rose and others on his team were of Irish descent.

The Cold War years unsurprisingly proved to be a popular time for athletes to put their political views across. When China withdrew from the 1960 Olympics in protest at Taiwan, then recognised by the west as the legitimate China, taking part. The IOC then asked Taiwan not to march under the name ‘Republic of China’. While considering boycotting the games, the Taiwanese delegation instead decided to march into the opening ceremony with a sign reading “under protest”.

The same year as the Smith and Carlos protest, a Czechoslovakian gymnast kept her face down during the Soviet national anthem, in protest at the brutal crackdown of the Prague Spring earlier that year. And that was not the only act of defiance against the Soviet Union. During the controversial 1980 Moscow Olympics, boycotted by a number of countries over the USSR invasion of Afghanistan, the athletes competing also took a stand. The likes of China, Puerto Rico, Denmark, France and the UK marched under the Olympic flag in the opening ceremony, and raised it in the medal ceremonies. After winning gold, and beating a Soviet opponent, Polish high jumper Wladyslaw Kozakieicz also made a now famous, symbolic protest gesture towards the Soviet crowd.

But there are also more recent examples. At Athens 2004, Iranian flyweight judo champion Arash Miresmaeili reportedly ate his way out of his weight category the day before he was set to fight Israeli Ehud Vaks. “Although I have trained for months and was in good shape, I refused to fight my Israeli opponent to sympathise with the suffering of the people of Palestine” he said. A member of the South Korean football team which beat Japan to win bronze at the 2012 London Olympics, celebrated with a flag carrying a slogan supporting South Korean sovereignty over territory Japan also claims.

When the debate on political expression comes up, the argument of “where do we draw the line” often follows. If the IOC is to allow messages of solidarity with Russia’s LGBT population, should they allow, say, a Serbian athlete speak out against Kosovan independence? Or any number of similar, controversial political issues? Is it not easier to simply have a blanket band, and leave it at that?

The problem with this is, as much as the IOC and many other would like it, the Olympics, with all their inherent symbolism, simply cannot be divorced from wider society or politics. The examples above show this. With regards to Sochi in particular, the issue is pretty straightforward — gay are human rights. Some have argued we should boycott a Olympics in a country that doesn’t respect the Universal Declaration on Human Rights, or indeed the Olympic Charter. This is not happening, so the very least we can is use the Olympics to shine a light on gay rights in Russia. At its core, the Olympics are about the athletes — they are the most visible and important people there. It remains to be seen whether any of them will take a stand for gay rights, outside cordoned-off protest areas, in the slopes and on the rink, where the spotlight shines the brightest. And if they do, they should have our full support.

This article was posted on 13 Dec 2013 at indexoncensorship.org