(Illustration: Shutterstock)

The idea, or perhaps ideal, of innocence plays a complex part in our society: We value it, but still have a very strong sense of its limited use. In a five-year old, innocence is a delight; in a 25-year old an annoyance; in a 45-year old? A tragedy.

This is no bad thing; central to our modern conception of children’s rights is the notion that they are blameless: An innocent child cannot be held responsible for, say, the actions of a sexual abuser. An innocent child does not have the faculty to enter into a contract to sell their labour: An innocent child cannot start a physical fight with a grown-up parent.

By the time we reach majority, we are supposed to be able to negotiate our way through the world. We probably retain some of that innocence well beyond the age of 18, but society has to draw a line somewhere.

There is a downside to this right and justified urge to uphold the immaculate status of the child; it comes in the form of the ever-returning moral panic.

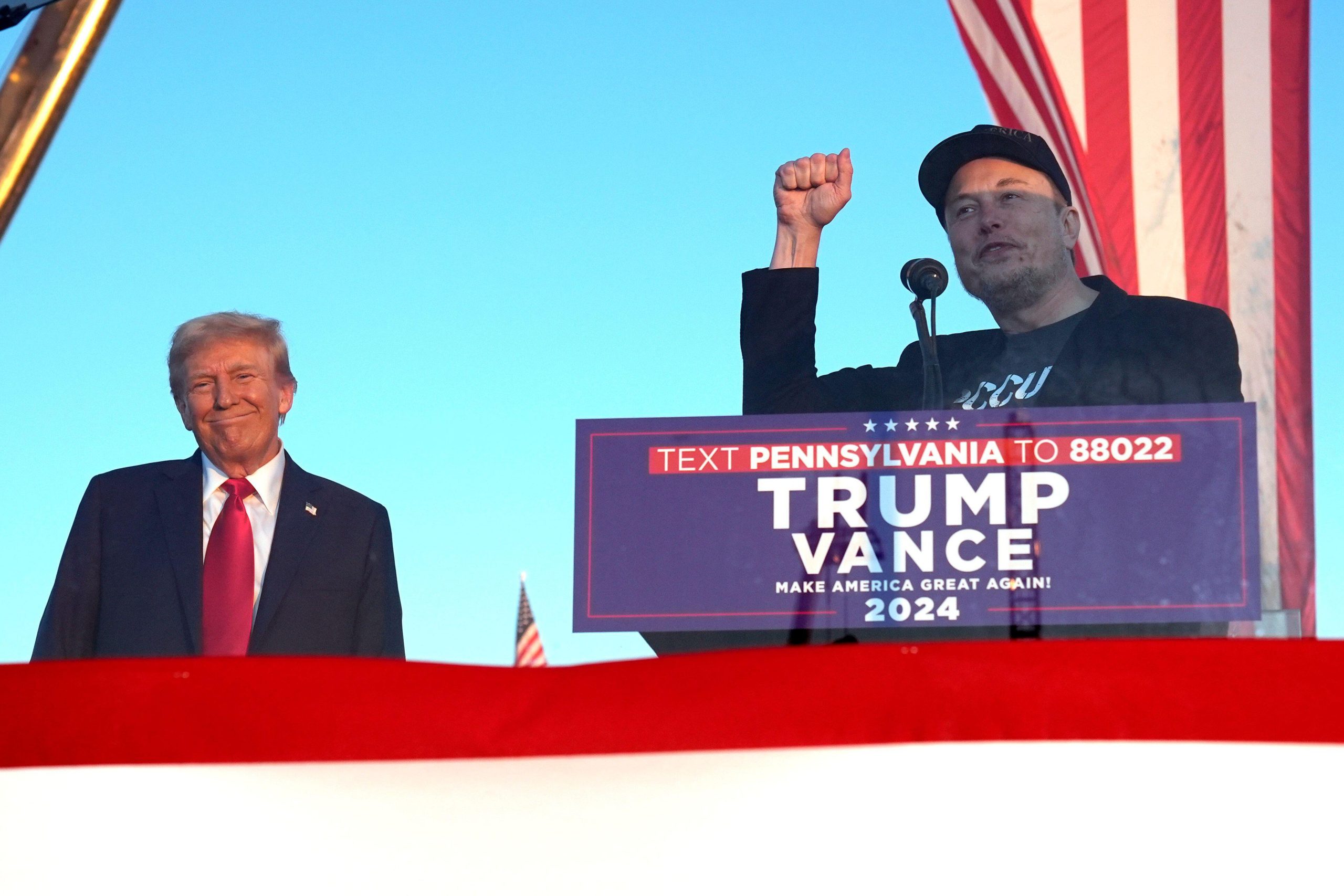

This week, the Chief Inspector of Constabulary, Tom Winsor, in his assessment of the “state of policing” in England and Wales for 2012/2013, warned of the dangers of smartphones and their capability for warping young minds.

“Modern technology,” Winsor notes ”provides new and more effective ways for children to be abused, pursued and drawn into crime. Moreover, violence and sexually explicit material available to children on smartphones and other devices desensitise them and distort and confuse their perceptions of normal behaviour.”

The first part is most likely true, at least the “new” part, though I would be wary of the idea that new technologies are somehow more “effective” for child abusers. The majority of incidents of abuse are perpetrated by people already close to children, not strangers.

But the second assertion, on “desensitisation”, is as old as the hills, and fits into a pattern of moral panics that has been present for decades. Elsewhere, Winsor cites the many causes of crime, which include:

“social dysfunctionality, families in crisis, the failings of parents and communities, the disintegration of deference and respect for authority, the fears of teachers, alcohol, drugs, a misplaced and unjustified desire or determination to exert power over others, envy, greed, materialism and the corrosive effects of readily-available hard-core pornography and the suppression of instincts of revulsion to violence through the conditioning effect of exposure to distasteful and extreme computer games and films.”

This list introduces the great friend of the moral panic, declinism (a concept explored by Index on Censorship chair David Aaronovitch in a BBC documentary); British society has been in decline, roughly since the Suez crisis, or the time the first Teddy Boy swung his first bicycle chain in anger.

British young people are in danger of corruption, now more than ever; “now” being any given moment in the past 60 years. Bill Haley, Mick Jagger, David Bowie, Suzi Quatro, Space Invaders, “snuff movies”, Snoop Doggy Dogg, Chucky from Child’s Play, Mortal Kombat, Manhunt, Grand Theft Auto, “Skins parties”… all have presented a clear corrupting influence on young people.

And yet, civilisation has survived. In fact, as Martha Gill points out in the Daily Telegraph, today’s young folk are remarkably pure and well-behaved.

The country has not, in fact, gone to the dogs. More to the point, there was never an age of innocence, either for young people or for the nation.

In the years 1947/1948, which many on both the right and left might consider halcyon days for Britain, now-national-treasure Richard Attenborough played a teen killer in two consecutive films – Pinky in the adaptation of Graham Greene’s Brighton Rock, and Percy Moon in Dulcimer Street, the adaptation of Norman Collins’s London Belongs To Me.

Both are young men with wild ideas (though naive Percy cannot come anywhere near the badness and vindictiveness of Greene’s monstrous, tortured Pinky). To use Winsor’s language, both display, to varying degrees, those dread traits “materialism” and “a misplaced and unjustified desire or determination to exert power over others”. Their creators clearly find sympathy in them, but clearly are working from a template of a corrupted modern youngster. Notably, in Dulcimer Street, Percy is an avid reader of the new, American (read “alien to old England), detective and thriller comics.

The combination of declinism and moral panic reached its acme in spring of 1993, after two 10-year old boys took a two-year old toddler from a Bootle shopping centre to a railway sidings, where they tortured and killed him.

The murder of James Bulger by Jon Venables and Robert Thomson was as inexplicable as it was horrific. But proved, for those looking for the evidence, that British society had reached a devastating new low, Moral panic-ers soon found out why: The, silly, schlocky horror movie “Child’s Play 3” was the culprit. Apparently one of the boys’ parents had rented the film. That was it, in spite of their being scant evidence the boys had even seen the film. In fact, as Professor Stan Cohen noted in his updated version of Folk Devils and Moral Panics, “a senior Merseyside Police Inspector revealed that checks on the family homes and rental lists showed that neither Child’s Play nor anything like it had been viewed.”

The pattern has repeated since, most particularly in erroneous reports in 2004 that the videogame Manhunt had influenced a teenager who killed a friend, in spite of police insistence that the game had nothing to do with it.

Declinism is insidious in that it gives young people and their culture (pop music, games) a raw deal. Moral panics, while they should be resisted, are at least understandable. But to be genuine in our efforts to protect young people and their innocence, we should remain rational, rather than merely seeking out the latest scapegoat. More often than not, it turns out that the kids are all right after all.

This article was published on April 3, 2014 at indexoncensorship.org