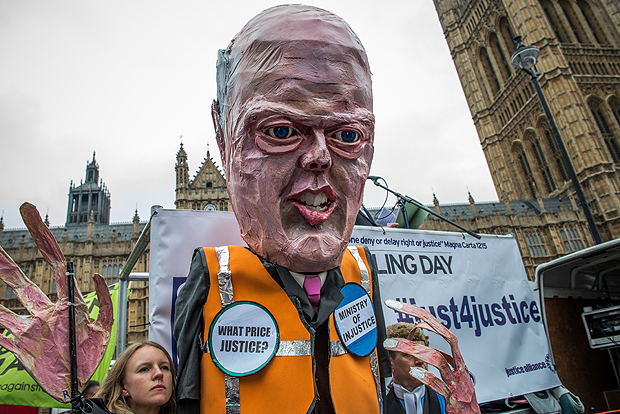

Activists marched with an effigy of justice minister Chris Grayling in March to protest legal aid cuts. (Photo: Velar Grant / Demotix)

The British government is making it easier for those in power to break the law – and it’s using a fantasy about left-wing pressure groups to justify it.

Judicial review is becoming a real pain for those who run Britain. However much they like to think they’re above the law, they frequently get reminded that they’re breaking it. Last October, for example, health secretary Jeremy Hunt’s attempt to implement cuts at Lewisham hospital was stymied by a judicial review funded by campaigning organisation 38 Degrees.

By then David Cameron had already announced his determination to clamp down on “time-wasting” judicial reviews. What’s motivating this move is the sheer number of cases now being brought. There were around 15,700 judicial review cases in 2013, up from around 4,300 cases in 2010. Judicial review – the way in which the legality of the state’s actions can be tested by judges – is not clogging up the courts, though. Just a fifth of those put forward were granted permission to succeed in 2012.

The executive’s correct response should be to do more within the law, not outside it. Instead justice secretary Chris Grayling is leading a push to impose a chilling effect on judicial review that opponents say would make the process punitively expensive – effectively making it that much easier for the executive to get away with it.

“Britain cannot afford to allow a culture of left-wing-dominated, single-issue activism to hold back our country from investing in infrastructure and new sources of energy and from bringing down the cost of our welfare state,” he wrote in an article for the Daily Mail.

“We need to make decisions quicker and respond to issues more quickly in what is a true global race… the left does not understand this.”

Senior members of the judiciary don’t understand it either. “We note that the consultation paper does not contain any evidence of inappropriate use of judicial review as a campaigning tool, and it is not the experience of the senior judiciary that this is a common problem,” they observe drily.

Their bafflement has not stopped Grayling from manoeuvring inside the corridors of parliament. He’s been attempting to win over MPs by talking up these changes as a power grab by parliament, not the government. Yet because it’s ministers who control what goes on in the Commons, Grayling is effectively seeking more power for himself and his colleagues, not backbench MPs. If nothing gives in the parliamentary process, he’s going to succeed.

What’s now working through the Commons in the criminal justice and courts bill is a cocktail of measures which together will cut back on ordinary people’s access to justice.

Top of the list is a move which requires judges to dismiss any judicial review claims where an abuse of the process wouldn’t have made a difference to the end result. Take a new zebra crossing application, for example. If 40 homes are affected and only 39 are notified beforehand, a judicial review could be brought by the 40th person complaining of the result. But if all 39 had already backed the crossing, should the court’s time really be taken up?

Absolutely, civil liberties group Liberty argues. “Even where individuals are not satisfied with the outcome of a decision-making process, the fact that they have been given a fair hearing often serves to satisfy their sense of justice and promotes trust in state institutions and democratic processes,” its submission to the MoJ states.

Under the government’s proposals, the concept of a fair hearing is being abandoned completely.

Even those cases which do still qualify may find they miss out because, under the government’s original proposals, the timeframe for bringing a claim is being halved from three months to six weeks.

But it’s worse than that. In addition to making it harder for judicial reviews to get into court by changing the rules, the government is trying to put many third-party groups getting involved altogether.

In many cases it’s charities like Liberty which get involved – relatively small organisations that could never afford to pay full legal costs if they lose. Yet that is exactly what the government is going to make them do.

The Ministry of Justice’s (MoJ) own impact assessment has already worked out the implications of this change. “Interveners may be less inclined to intervene voluntarily if they were more exposed to the costs their actions place on claimants and defendants,” the document states. That’s putting it mildly.

What about the Liberal Democrats, who in opposition styled themselves as the defenders of personal freedoms? They have left the wrangling with ministers to MP Julian Huppert, who is ignoring most of the measures in favour of the interveners clause. His goal is to achieve a meaningful concession – and believes he may be getting somewhere.

“I was very pleased the government has agreed to look at alternative wording on interveners,” he says.

“The wording as it currently stands is completely unacceptable to me because it would stop very good meritorious interventions from happening because of the chilling effect.”

Huppert has been the victim of some cruel jibes from Labour’s shadow justice minister Andy Slaughter, who has predicted “some nugatory or insubstantial concession will be made in the future”. It remains to be seen who will be proved right. If nothing changes, many third-party ‘interveners’ will decide it’s simply not worth the risk.

Eventually the bill will arrive in the Lords, when peers are expected to tear into the proposals. Lord Pannick, who has proved one of the spikiest thorns in this government’s side over the years, is among those who have already spoken out against the ‘unconstitutional’ nature of the changes.

Perhaps ministers will be more prepared to make concessions in the second chamber. They certainly weren’t interested in responding to the responses to their consultation on judicial review, which were weighted about 10:1 against the government’s proposals.

“We want there to be a rebalance of what has, in my view, become a risk-free enterprise for many organisations and for which the taxpayer is shouldering the burden,” justice minister Shailesh Vara explained during the committee stage debates.

“We are seeking to set a sensible position on precisely when the taxpayer is expected to foot the bill for others’ decisions. This is not purely a question of quantum but also one of the good stewardship of public finances.”

Grayling is having a tough run-up to Easter. He’s been criticised over the prisoner books ban. He’s been condemned for presiding over sweeping reductions in legal aid. Now he is going further still with judicial review. As Vara’s comments reveal, Grayling is literally cutting justice once again.

Valerie Vaz, the Labour backbencher, has this to say: “It isn’t clear what apparent mischief the government are trying to prevent, other than to interfere with the workings of the court.

“We ought to remember the dictum, ‘be ye ever so high, the law is above thee’, but the government appear to be saying, ‘be ye ever so high, the government are above thee’.”

This article was posted on April 4, 2014 at indexoncensorship.org