Enshrining the right to be forgotten is a further step towards allowing individuals to take control of their own data, or even monetise it themselves, as we proposed in the Project 2020 white paper (Scenarios for the Future of Cybercrime). The way the law stands in the EU currently, we have legal definitions for a data controller, a data processor and a data subject, an oddity, which lands each of us in the bizarre situation where we are subjects of our own data rather being able to assert any notion of ownership over it. With data ownership comes the right to grant or deny access to that data and to be responsible for its accuracy and integrity.

In response to the ECJ judgement, I have seen a lot of commentators cry “censorship” and make all kinds of unsupportable comparisons with book burning (or pulping), these reactions are misguided and out of all proportion to the decision made. Let’s remember what has been decreed is that an individual has the right to request that certain information be de-indexed from search and aggregation engines. That request is not an order and each one must go through due process and consideration before any changes are made, including if necessary consideration by a court of law. Individuals are not being granted the right to rewrite history, they are being given the right to request, within the strictures of the law, that certain publishers cease to publish information about them which they consider deleterious. They are being given the right to be able to manage their own image online, it seems bizarre that this right is seen by some as the repression of free speech when in effect it gives the individual the right to speak up about something which they find personally damaging.

In 2009, an organisation called “The Consulting Association” was found to be operating a commercial blacklist service to the construction industry. This organisation held detailed files on construction professionals, listing their names, family relationships, newspaper cuttings and details of criminal records. Several global construction companies paid for access to this data and over 3000 individuals were potentially prevented from gaining employment in their industry. Of course this shocks us, and rightly the Information Commissioner took action, seizing the data in question and informing those affected. In many ways a search engine’s constant aggregation of data and even more its contextualisation and publication of that data as relevant to a given name fulfils the same function, now you have a right to at least influence it, even if you cannot stop it.

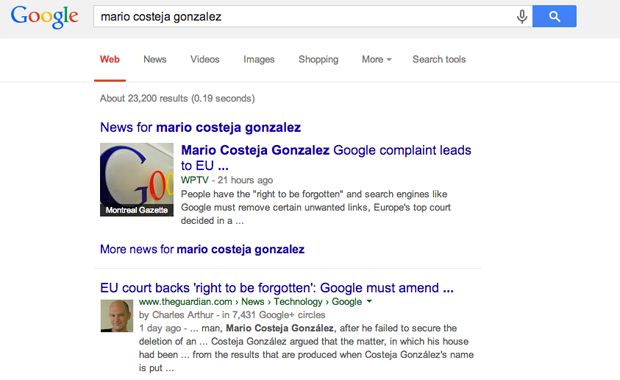

The ruling is the right one. The court recognises that information that was “legally published” remains so and that the individual has no right to censor it. However, they also recognise that search engines collect, retrieve, record, organise, store and disclose information on an on-going basis and that this constitutes “processing” of data under the EU directive. Further, given that the search engine determines the means and purpose of their own data processing, they are also a “Data Controller” under that directive and again must fulfil the legal requirements of such an entity; any other court decision would weaken that whole directive beyond repair. The entirety of information turned up in response to a search on a person’s name, represents a whole new level of publishing and the discrete items of information would have been very difficult, if not impossible, to put together in the absence of a search engine.

While there will of course be technical and procedural issues that arise from this ruling and there will doubtless be individuals seeking to evade public scrutiny, any other decision on this would have simply blown away the EU Data Protection directive and that is not something any us should be advocating. Consider the wider ramifications of this decision, if a search engine is now a “Data Controller” in the eyes of the law, shouldn’t they be notifying us whenever they collect information about us? Would it be a breath of fresh air if you could begin to understand the wealth of information out there about you and begin to realise an income from it yourself? Personal information is a commodity that commands a financial premium and right now it is others who realise those gains. It’s time we advocated for real ownership of our own data.

Before personal data became a commodity mined by corporations and attackers alike, the need for a legal stance on the identity of the “owner” of data relating to oneself may have seemed laughable. However that has landed us in the situation of today when entities that mine and monetise that same data can refer to this very welcome EU ruling as “disappointing”. Commercially disappointing it may be, however it is a step, albeit a small one, in the right direction.

This article was originally posted on May 13, 2014 at countermeasures.trendmicro.eu