For the last two decades the stubborn, powerful myth that the creative arts and the Protestant working class in Northern Ireland do not go together has been regularly proclaimed.

For the last two decades the stubborn, powerful myth that the creative arts and the Protestant working class in Northern Ireland do not go together has been regularly proclaimed.

Closer reading reveals a plethora of Protestant dramatists including, but not limited to: Sam Thompson, Stewart Parker, Ron Hutchinson, Christina Reid, Graham Reid, Marie Jones, and Gary Mitchell. This is of course a typically unfortunate sectarian head-count, but a necessary one in light of matter-of-fact declarations from Irish Republicans that Ulster Protestants have ‘no culture’, and – perhaps more damagingly – the identical conviction of a large number of working class Protestants themselves.

With this is mind it is worth distinguishing between ‘loyalist’ and ‘Protestant working class’ voices. The phrases have become interchangeable (despite the way the Protestant electorate has long given loyalists the cold shoulder), and many local and international commentators in the media and academia continue to refuse the distinction. On the other hand, with the exception of the lively 1982 community play This is It!, loyalists are indeed without any real lineage in the theatre.

It is therefore vital that Ulster loyalists take their place on the stage, a process which began on 1 May when Bobby Niblock’s play Tartan opened in East Belfast’s Skainos Centre before going on to close the city’s Cathedral Quarter Arts Festival. A production of the recently-formed Et Cetera theatre company, this was an avowedly loyalist exercise in the sense that Niblock is an ex-prisoner depicting one of its stories. Initially the Tartans fought other gangs from within the same community but many went on to join loyalist paramilitary groups, a difference and tension the play explores.

At an Index on Censorship symposium held in the University of Ulster’s Belfast campus on 3 May, I was charged with leading one of four breakout sessions exploring why loyalist voices are under-represented in the theatre. The challenge facing the Et Cetera group was brought home when only one person from this comfortable set showed up, perfectly encapsulating part the problem. The one major complaint of loyalists in post-Troubles Northern Ireland is that their voice is simply ignored. I was initially apprehensive about spearheading a discussion even mentioning ‘loyalism’, as it is now a pejorative term of abuse. The way the conference attendees reacted typically reflects the complete unwillingness to engage with this disillusioned section.

Many loyalists have hitherto been convinced that the best way they can make their voices heard is to block roads and intimidate. They feel the ‘peace process dividend’ has nothing to offer them, while report after report pitches the Protestant working class male right at the bottom of the educational attainment table (only just in front of Irish traveller and Gypsy/Roma, according to the latest Peace Monitoring Report). These are the men who find themselves languishing in the back of police vans and holding cells at the end of an evening of rioting, as well as being the first target for the paramilitaries.

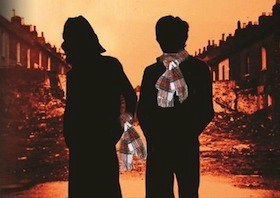

No-one would be so naïve as to believe that a play alone could stop violence, but seeing a play – like all art – can soften human beings as well as advance understanding. The late Seamus Heaney once said of his own medium that ‘It can eventually make new feelings, or feelings about feelings, happen’, and the creative process often leads to self-examination. In Tartan two young men reflect while they assemble a crate of petrol bombs: it’s their future they’re on the verge of hurling away along with the incendiaries. A diversity of viewpoints are similarly on show. Some of the boys are already hard-liners; others remind us that most Catholics don’t support the IRA. While empathetic to its young, exploited protagonists, it is also upfront about their mistakes and prejudices.

Tartan has flaws – including a noticeably stronger second half – but it is one hell of an opening salvo. The energy of these young males reverberates off the stage, giving speech and form to a violence which continues to scar the North’s streets, as well as highlighting the essence of the Et Cetera group itself: as an outlet for new stories and energies previously untapped.

The dangers of a loyalist underclass are unlikely to be apparent to an English or international audience. They remain rather less deadly than dissident republicans, but Tartan’s relevance – anchored in the perspective of misled young Protestant men – becomes especially resonant in the wake of the increased recruiting and activities of the most serious loyalist paramilitaries.

The Man Who Swallowed a Dictionary, a play about David Ervine – another ex-prisoner who died prematurely of a heart attack in January 2007 – is Niblock’s follow-up project. Earning this (provisional) title in real life for being articulate in a culture which does not value articulacy, Ervine served his sentence in the same prison as Niblock and had represented one of the few political voices for disempowered loyalists. The loss was enormous, but the return of this voice is next.

This article was originally posted on May 30, 2014 at indexoncensorship.org