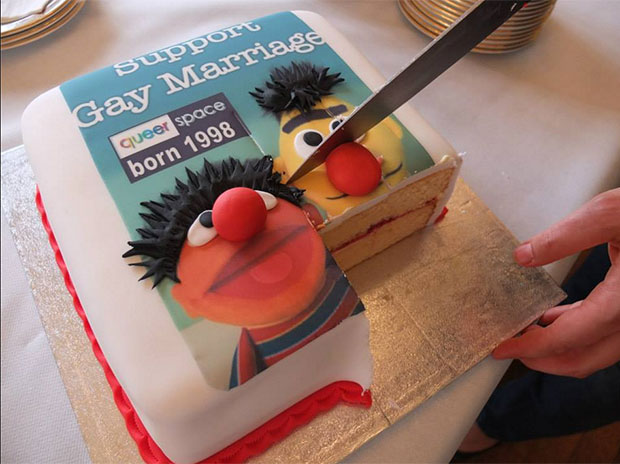

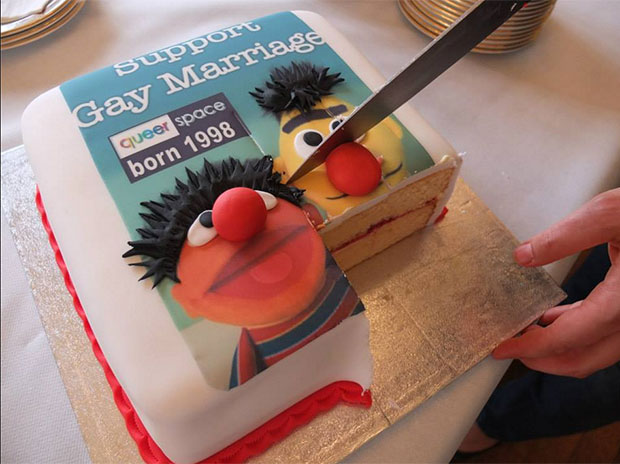

QueerSpace Belfast / Facebook

Last Sunday, as Northern Ireland’s footballers prepared to play Finland in a European Championship qualifier, protesters gathered outside Windsor Park, the team’s Belfast home.

The assembled were members of the Free Presbyterian Church. They were angered by the fact that Northern Ireland were playing on a Sunday – the Sabbath – for the first time ever.

Reverend Raymond Robinson told the Press Association: “Our opposition is to the breaking of observance of the Lord’s day.

“We believe in the Sabbath being kept holy. It seems more and more that the football agenda is being driven by the television companies and not what God says, or what public opinion is.”

Commentator Newton Emerson was, like many, blase about the protest, tweeting “I think these people are harmless enough now to just count towards our wonderful diversity.”

Be that as it may, Christian fundamentalism still plays a huge role in public life in Northern Ireland. While the old demands for Biblical propriety may seem archaic, a new struggle has emerged over what many religious people in the country see as threats to their religious freedom and way of life. And a cake has become the latest flashpoint.

Asher’s bakery is a business run by a family known for its Christian beliefs. It is named after one of the Biblical Twelve Tribes of Israel. Last summer, the bakery was asked to provide a cake by Gareth Lee, a volunteer for LGBT group QueerSpace.

Lee had requested a cake decorated with a picture of Sesame Street’s Bert and Ernie and the slogan “Support Gay Marriage”.

The bakery initially accepted the order, before then informing Lee that it could not fulfil the deal. The case went to Northern Ireland’s Equality Commission, and, between the jigs and reels, is now in the hands of district judge Isobel Brownie, who will rule on Monday whether the Christian bakers engaged in unlawful discrimination by not delivering the pro-same sex marriage cake.

Meanwhile, the “gay cake” case has raised the spectre of a “conscience clause” in equality legislation in Northern Ireland.

The whole situation is, quite frankly, pitiful. One can preach it, validly, both ways: fundamentalist bigots out of touch with the modern world, and inflicting their bigotry on others, or God-fearing, humble folk sticking by their beliefs in the face of an onslaught they didn’t invite.

I can’t help feel sympathetic towards the McArthurs, the family who own the bakery. Karen McArthur told the court that she had initially accepted the order to avoid embarrassment. Colin McArthur said “On that day I didn’t make a clinical decision. I was examining my heart. I was wrestling it over in my heart and in my mind.” He was, apparently, “deeply troubled”. “We discussed how we could stand before God and bake a cake like this promoting a case like this…”

On the other hand, Gareth Lee said he was left feeling like a lesser person after he was told his order would not be fulfilled.

This shouldn’t be down to who was more upset or offended, but then, on what criteria can we judge it? I don’t think it’s necessarily true to say that Lee is entitled to have any message he wants put on any cake by any person. The prosecution, correctly, pointed out that the message was rejected because of the word “gay”. The defence lawyers suggested that a ruling against the McArthurs could lead to a situation where devout Muslims were legally obliged to decorate cakes with images of Muhammad. While “you wouldn’t say that about the Muslims” is a tedious argument, and one deployed increasingly often by Christians, it’s not, in this case, an entirely unreasonable position.

Hardline Christians see homosexuality as a (wrong) choice people make, or a psychological disorder. I recall watching the Reverend Willie McRea, an MP, once, being asked what support he would offer to a constituent who was a victim of homophobia. McRea replied that he would advise the young man not go down that route: basically, the best way to prevent homophobia is to stop being gay.

Meanwhile, Iris Robinson, wife of Democratic Unionist Party leader Peter Robinson, firmly believes that one can be counselled away from homosexuality.

These people are odd, certainly, but they are not fringe characters who can be dismissed as irrelevant to mainstream society in Northern Ireland.

And even if these views were not mainstream, that would not make the fundamentals of the case any different. But it does seem as if the Equality Commission is trying to drag a segment of Northern Irish society kicking and screaming into the secular world.

So who’s right? Who should win? Reader, I am about to break the columnist’s solemn covenant and admit: I don’t fully know. This is not as clear cut a case of discrimination as, say, barring a gay couple from a Bed and Breakfast: if the McArthurs had simply refused to sell a cake to Lee, that would be clear cut. But the cake was loaded, so to speak. Should this tricky case lead to a “conscience clause” in equality legislation, then one can imagine legitimisation of genuinely discriminatory practices.

At the same time, the McArthurs, are wrong, and one’s initial inclination is to side with the gay rights activist against the religious fundamentalists. But that’s the problem with defending freedom of conscience, (and its expression in freedom of speech). Everyone’s conscience is different.

Northern Ireland beat Finland 2-1, by the way. God’s clearly not very troubled by Sunday football.

This column was posted at indexoncensorship.org on April 2, 2015