When publishers are too intimidated to print even novels that may offend, it shows how far we’ve lost our way on free speech, writes

Jo Glanville

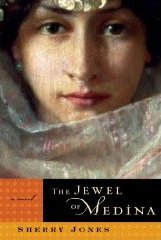

The firebomb attack this weekend on the publishing house Gibson Square in London was an assault on one of the bravest publishers in the business. Three men were arrested under the Terrorism Act 2000 on Saturday morning, suspected of attempting to set fire to the premises. Martin Rynja, who runs Gibson Square, is due to publish Sherry Jones’s novel about Mohammed’s wife Aisha, The Jewel of Medina, next month. Random House had pulled out of publishing the novel in August, stating that it had been advised that ‘the publication of this book might be offensive to some in the Muslim community’ and that ‘it could incite acts of violence by a small, radical segment’.

This is not the first time that Rynja, owner of a small, independent publishing house, has shown himself to have more gumption and appetite for controversy than the big boys. Four years ago, he published Craig Unger’s House of Bush, House of Saud after Random House, once again, pulled out – this time for fear of libel action. He is also the publisher of OJ Simpson’s If I Did It and Alexander Litvinenko’s Blowing Up Russia.

Rynja’s support for free speech is proving to be exceptional, as is his courage in standing up to bullies, at a time when other publishers will surrender at any intimation of legal action – particularly from litigious Saudis. Rynja, who trained as a lawyer, has shown that capitulation need not be inevitable. I can only hope that the shocking attack on his office will not dim his determination — but he will need support.

Random House dropped The Jewel of Medina in anticipation that offence might be caused in an extraordinary instance of pre-emptive censorship. Let’s remember the similarly dire predictions that were made when Geert Wilders released his provocative film Fitna, which links Islam to terrorism – it was in fact a non-event.

Yet, in this instance, the row that ensued once the story broke about Sherry Jones’s novel has, like a self-fulfilling prophecy, served to escalate the very scenario that Random House was apparently seeking to avert. It is most telling that they sent a work of fiction out to academics for approval in the first place — since when was a historian, however smart and literate, a suitable judge of whether a novel should or should not be published? Surely the only grounds for publishing a novel are whether it is of literary merit? One of the academics they consulted, Denise Spellberg, was reported as saying: ‘You can’t play with a sacred history and turn it into soft-core pornography.’ Why not? This is one person’s subjective view of a novel — it should not be grounds for censorship.

Random House’s actions show just how far we have lost our way in this debate over free expression and Islam: the level of intimidation, fear and self-censorship is such that one of the biggest publishers in the world no longer felt able to publish a work of creative imagination without some kind of dispensation. Jones’s book does not claim to be a piece of history — it’s a work of invention.

It was also disingenuous of Random House to suggest that the novel might incite violence. Certain members of the population might choose to commit an act of violence, but that is not the same as the book itself inciting violence. To pass the responsibility in this way to the novel was a betrayal of the author and of free speech. So it was left to a small publisher, with none of the resources a major publishing house can enjoy in such a time of crisis, to stand up for principles. Now that Rynja has come under attack, it is more necessary than ever to counter any justification of censorship on the grounds of offence (that may or may not be caused) and to condemn any intimidation tactics.

This whole affair — from Random House’s decision to drop the book, to the attack this weekend – is evidence of a worrying trend. Twenty years since The Satanic Verses was published, in the 60th-anniversary year of the UN Declaration of Human Rights, we are facing a crisis for free expression. Yet the threat comes not only from those who commit acts of violence, but from those who ostensibly support human rights.

Respect for religion has now become acceptable grounds for censorship; even the UN secretary-general, Ban Ki-moon, has declared that free speech should respect religious sensibilities, while the UN human rights council passed a resolution earlier this year condemning defamation of religion and calling for governments to prohibit it. As the writer Kenan Malik has so astutely pointed out: ‘In the post-Rushdie world, speech has come to be seen not intrinsically as a good but inherently as a problem because it can offend as well as harm …’ Censorship, and self-censorship, Malik observes, have become the norm. What we have seen, over the past two decades, is an insidious new argument for curbing free speech become increasingly acceptable.

Martin Rynja has consistently set an example to us all in not being cowed by outrage, convention and legal action. It’s an independent spirit that we urgently need to cherish, support and emulate — and it’s not only free speech groups like Index on Censorship that should be standing up for him.

This article was originally published in the Guardian