27 Sep 2024 | News and features, Newsletters, United Kingdom

Today two young British activists, Phoebe Plummer and Anna Holland, have been sentenced to prison after being found guilty of criminal damage following a stunt at London’s National Gallery. The pair, part of Just Stop Oil (JSO), famously threw Heinz tomato soup at Vincent Van Gogh’s Sunflowers back in October 2022. At Southwark Crown Court, Judge Christopher Hehir sentenced Plummer to two years in prison while Holland was jailed for 20 months. Judge Hehir said the pair “couldn’t have cared less” if the painting had been damaged. But please note no person or painting was harmed in the making of this protest. The iconic painting’s frame, however, was (hence the charges). Should they be punished for the damage caused? Perhaps. But surely a simple fine, a suspended sentence, or community service would do? Jail time (and quite significant jail time at that) is problematic to say the least and follows a pattern of climate protesters being punished harshly in a way that makes it harder for others to join their cause and chorus.

Under the last government a series of legislation was introduced (the Policing, Crime, Sentencing and Courts Act 2022, the Public Order Act 2023 and Serious Disruption Prevention Orders), each with the aim of restricting peoples’ right to protest and increasing the punishment for those who fall foul of the new laws. Their scale was evidenced earlier this summer when other JSO protesters were sentenced to four and five years’ imprisonment respectively for planning protests on the M25. Commenting at the time of the sentences Michel Forst, the UN’s special rapporteur on environmental defenders, said they should “put all of us on high alert on the state of civic rights and freedoms in the United Kingdom.”

It’s not just in the UK that the rights of non-violent protesters are being threatened. As Mackenzie Argent reports for Index here, it’s happening throughout Europe, Australia and North America. And while Argent’s article argues that it’s most pronounced in the UK, if the current Italian government gets its way the UK won’t be the worst for long. There, a new security bill proposes outlawing hunger strikes, one of the most powerful forms of protest open to a political prisoner, amongst other measures. All of the countries cited above claim to be democracies and yet these actions make the label look more decorative than substantive. It’s the same story in Israel. Last weekend soldiers marched into the Al Jazeera office in Ramallah, confiscated equipment and closed it for an initial 45 days. Israel’s military said a legal opinion and intelligence assessment determined the offices were being used “to incite terror” and “support terrorist activities”, and that the Qatari-owned channel’s broadcasts endanger Israel’s security. The Israel Defense Forces (IDF) has been pressed on these points by organisations like the Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ) but has not responded (and indeed when the IDF has made similar accusations in the past, it has provided little evidence to hold them up to scrutiny. See the BBC report here for example). So it simply looks like another attack on media freedom, a way to silence an outlet that can (and should) report to the world what is happening in the West Bank.

People need to be able to protest and they need to be able to report the news. When these two essential pillars are shut down in countries like the UK, the USA, Israel and Italy, the dividing line between democracies and autocracies becomes thinner and the former’s ability to call out the latter on their human rights violations becomes weaker.

24 Sep 2024 | News and features

Banned Books Week is here once again. And so too are more stories of books being censored across the world. This week, Pen America reported that the number of book bans in public schools has nearly tripled in 2023-24 from the previous school year.

While the week-long Banned Books Week event, supported by a coalition including Index on Censorship, looks largely towards bans in the USA, we’re taking a moment to reflect on global censorship of literature. We asked the Index team to share what they think is the most ridiculous instance of book censorship, from the outright silly to the baffling but dangerous. Some of these examples verge on amusing — the Chinese Communist Party (CCP)’s aversion to talking animals, for example — but the bans that have ended in attempted murders just go to show that the practice of book banning itself is completely nonsensical, and can lead to real harm.

Banned Books (Photo by Aimée Hamilton)

Too many talking animals

You don’t have to have children to imagine what a clichéd kids book might look like. Yes, you’ve guessed right – animated animals. Tigers, mice, dogs – they’re all common in children’s literature. But the Chinese authorities have an uncomfortable relationship with our furry friends.

In 2022 a Hong Kong court sent five people to prison for publishing a series of books called Sheep Village (and of course they banned the books too). To be fair these illustrated books, aimed at kids aged four to seven, didn’t code their political messages well: a flock of sheep (stand-in for Hong Kongers) peacefully resist a savage wolf pack (the guys in Beijing). So this might not be the most absurd example, though it did feel like an absurdly low moment.

However, what was clearly absurd on all levels was the 1931 ban of Alice in Wonderland by the governor of Hunan Province. The book’s crime? Talking animals. Apparently they shouldn’t have used human language and putting humans and animals on the same level was “disastrous”. What unites the CCP with the Republic of China that came before it? Unease around anthropomorphised animals it would seem.

Too many banned books

Ban This Book by Alan Gatz, a book about book bans, has been banned by the state flying the banner for banning books. This is not a tongue twister, riddle or code. It is the crystallisation of the absurdity of banning books.

In January 2024, the book was banned in Indian River County in Florida after opposition from parents linked to Moms for Liberty. According to the Tallahassee Democrat, the school board disliked how the book “referenced other books that had been removed from schools” and accused it of “teaching rebellion of school board authority”. When you are trying to reshape the world in line with your own blinkered view it is probably best not to draw attention to it by calling out reading as an act of rebellion. Just a thought.

The book tells the story of Amy Anne Ollinger’s fight to overturn a book ban in her fictional school library. The book’s conclusion leads Amy Anne “to try to beat the book banners at their own game. Because after all, once you ban one book, you can ban them all”.

This tells us something – the self-harming absurdity of book bans is apparent to kids like Amy Anne but not to the prudish administrators and thuggish groups wielding their mob veto like a weapon. Groups like Moms for Liberty and their fellow censors obscure the darkness of our shared history by removing any reference to it and by pretending it did not happen — not by addressing the root causes or working to ensure it does not happen again.

- Nik Williams, policy and campaigns officer

Too Belarusian

In Belarus, numerous books in the Belarusian language by the country’s best classical and modern writers have been banned, especially following the 2020 presidential election and pro-democracy protests. Unbelievably, Lukashenka’s regime — often called the last dictatorship in Europe and backed by Russia — views Belarusian historical, cultural and national identity as a threat.

Many books in Belarusian have been labelled extremist and even destroyed from the National Library’s collection since the protests started in August 2020. This includes Dogs of Europe by Alhierd Baharevich, works by 19th century writer Vincent Dunin-Marcinkievich and 20th century poet Larysa Hienijush, among others.

- Jana Paliashchuk, researcher on Index’s Letters from Lukashenka’s Prisoners project

Too decadent and despairing

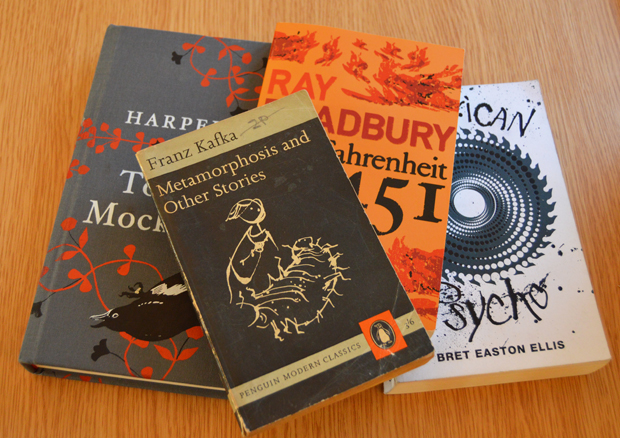

Franz Kafka’s The Metamorphosis, possibly the greatest short story ever written, was banned by both the Nazis and the Soviets. Being a Jewish author, the Nazis burned Kafka’s books on their “sauberen” (cleansing) pyres. But in the Soviet Union, his books were banned as “decadent and despairing”. This was clearly a judgement made by officials without much knowledge of the history of the novel, where so many titles are filled with human despair. Without these, we would not get the contrasting light of decadent writers like Oscar Wilde and JK Huysmans.

- David Sewell, finance director

Too mermaidy

One of my favourite books to read with my son is Julian is a Mermaid by Jessica Love. It’s a beautiful picture book where a young boy dreams of becoming a mermaid after seeing a school / pod (collective noun to be determined) of merfolk on the way to the Coney Island Mermaid Parade, then rummages around his nana’s home for a costume.

In various parts of the USA, Julian has been banned. In a school district in Iowa, it was flagged for removal under a law that “bans books that depict or describe sex acts”, which apparently also covers gender identity — there are definitely no sex acts in this book. In other districts, it’s been fully banned due to representing the LGBTQ+ community.

If book banners in the USA are really worried about kids becoming mermaids, then I’d like to know on what grounds. Because, quite frankly, I always wanted to be a mermaid, and if it turns out it was a viable option, I have some regrets. Personally, I’d be more concerned about Julian ripping down his nana’s curtains to make a tail, à la Julie Andrews making costumes for the Von Trapp children.

- Katie Dancey-Downs, assistant editor

Too accurate

In Egypt, Metro, the country’s first graphic novel by Magdy El Shafee, was quickly banned after publication in 2008 for “offending public morals”. This was likely due to the novel’s depiction of a half-naked woman, inclusion of swear words and general portrayal of poverty and corruption in Egypt during the former president Hosni Mubarak’s 30-year rule. The author was charged under article 178 of the Egyptian penal code for infringing “upon public decency” and fined 5,000 LE. It was eventually republished in Arabic in 2012.

- Georgia Beeston, communications and events manager

Too dystopian

Aldous Huxley’s 1932 dystopian classic Brave New World explores an imagined future centred on productivity and enforced “happiness” at the expense of individual freedom. Set in 2540, society has been stripped of families, with babies manufactured synthetically with specific characteristics, then forced into a predetermined “caste” system. People are encouraged to prioritise short-term gratification through casual sex and taking a “happiness” drug called soma, making them blissfully unaware of their imprisonment within the system.

Since its publication nearly 100 years ago, the novel has caused controversy globally. It was initially banned in Ireland and Australia in 1932 for eschewing traditional familial and religious values, then later banned in India in 1967 for its sexual content, with Huxley even being referred to as a “pornographer” for depicting a society that encourages recreational sex. It is still banned in many classrooms and libraries across America for a range of wild reasons, from use of offensive language and sexual explicitness to racism and “conflict with a religious viewpoint”.

But Huxley’s imagined future is one of horror. He uses themes of enforced, unfettered pleasure and a twisted genetic-based class system to express how humans’ complex problems and moral quandaries cannot be solved by scientific advancement alone. The main point of dystopian fiction is to tell a cautionary tale of the levels of exploitation that society could sink to, in order to save the world at large. While it was undoubtedly shocking and crass for its time, the fact that Huxley’s novel still ruffles feathers reveals a complete misunderstanding of allegory.

Too many lesbians

I first read Radclyffe Hall’s legendary lesbian novel, The Well of Loneliness, published in 1928, with bated breath as a young, closeted queer person. Her portrayal of young woman ‘Stephen’ Gordon and her romance with Mary Llewellyn was wildly liberating and satisfying to read. Of course, as a product of its time it is in many ways outdated and of course laced with problematic values, for example biphobia and misogyny. But it was hugely important in terms of normalising queer relationships over a century ago.

Shortly after publication, the book went to trial in Britain on the grounds of “obscenity” and was subsequently banned — but this is no Lady Chatterley’s Lover. There are no real ‘hot under the collar moments’. The only ‘obscenity’ was the portrayal of two women in a romantic relationship, even though (unlike male homosexuality), lesbianism wasn’t actually illegal in 1928.

- Anna Millward, development officer

Too friendly

The award-winning writer and painter Leo Lionni’s first children’s book Little Blue and Little Yellow (1959) is a short story for young children about two best friends who, one day, can’t find each other. When they meet again, they give each other such a big hug that they turn green.

Despite its important message about the power of love and friendship, the mayor of Venice decided to ban it from all preschools in the province for “undermining traditional family values”. It was one of more than 50 children’s books to have been banned just days after he took up the post after his election in 2015.

- Jessica Ní Mhainín, head of policy and campaigns

Too uncensored

As ironies go, the banning of Ray Bradbury’s Fahrenheit 451 may be the strangest. The novel describes a dystopian future in which books are banned and “firemen” burn any that are found – its title comes from the ignition temperature of paper.

In 1967, a new edition of the book aimed at high schools, known as the Bal-Hi edition, was substantially altered to remove swear words and references to drug use, nudity and drunkenness. Somehow, the censored text came to be used for the mass-market edition in 1973 and “for the next six years no uncensored paperback copies were in print, and no one seemed to notice”, wrote Jonathan R. Eller in the introduction to the 60th anniversary edition of the book.

Readers eventually realised and alerted Bradbury. He demanded that the publisher retract the censored version, writing that he would “not tolerate the practice of manuscript ‘mutilation’”.

- Mark Stimpson, associate editor

Too unflattering

It’s not altogether surprising that UK authorities attempted to prevent the autobiography of former MI5 officer Peter Wright, Spycatcher (co-written by Paul Greengrass), from hitting the shelves. The book did not present British intelligence agencies in a flattering light, and the government’s claims that they were suppressing its publication in the interests of security — rather than to save face — were eventually dismissed by the courts.

However, the ridiculous part about this book banning was that it only applied to England and Wales and the book was freely accessible elsewhere — including Scotland. This led to an absurd situation where newspapers around the world were reporting on the book’s contents while the press in England was subject to a gagging order, despite the information having already been revealed and books being easily shipped into the country. The ban was eventually lifted after it was acknowledged that the book wasn’t exposing any secrets due to its overseas publication.

- Daisy Ruddock, CASE coordinator

Too blasphemous

The most absurd book banning is also, arguably, the most serious in recent history. The Satanic Verses by Salman Rushdie was published in 1988 to deserved critical acclaim. It is a playful and complex novel that examines, among other things, the origins of Islam. The death sentence imposed on the author by Iran’s supreme leader Ayatollah Khomeini was fuelled by, and in turn itself fuelled an ideology that believes that a novel can be blasphemous and its author should be killed. It would be laughable if the consequences weren’t so deadly.

- Martin Bright, editor at large

6 Sep 2023 | Czech Republic, France, Greece, Hungary, Italy

Sofia Mandilara really likes her job. As a reporter for the Greek news agency Amna, she is “often at the forefront of important events”, she said. “Through us, people find out what is going on in our country.” But not all that goes on in Greece is reported. This is because Amna belongs to the Greek state and is subject to the office of Prime Minister Kyriakos Mitsotakis. Anyone who reports critically on his conservative government is censored, the 38-year-old said.

A similar situation exists at the Italian state broadcaster, Rai, which plays a major role in shaping public opinion. It is increasingly under the influence of Italy’s right-wing populist government. Immediately after taking office in October 2022, Prime Minister Giorgia Meloni filled all management positions with her followers. The two previous governments did the same, but none as radically as Meloni. Prominent reporters left and even high-profile journalist and anti-Mafia author Roberto Saviano’s show was cancelled after he tangled with Meloni. Positive reports about Meloni’s government, meanwhile, account for around 70% of all political news on Rai stations, according to the media research institute Osservatorio di Pavia.

Journalists at the Journal du Dimanche, France’s leading Sunday newspaper, have also suffered a radical change of regime. In the spring, Vivendi, owned by billionaire Vincent Bolloré, got the go-ahead to buy the publishing giant Lagardère, including the JDD. Bolloré publicly denies any political interest. But as with his acquisitions of CNews in 2016 and the magazine Paris Match last year, the buy-out was followed by a sharp turn in the editorial orientation of the JDD towards the far right.

State officials who demand censorship, party functionaries who misuse public broadcasters for their propaganda and billionaires who buy media to propagate their own political interests – what was long known only in Viktor Orbán’s Hungary – is spreading across Europe. The creeping decline in media freedom and pluralism has been documented for years by the Centre for Media Freedom at the European University of Florence, an EU-funded project. There is now “an alarming level of risk to media pluralism in all European countries”, researchers wrote in their annual report in June.

This puts Europe in a “desperate situation”, said Věra Jourová, the EU Commission vice-president for values and transparency. The Czech Commissioner has personal experience of life without a free press. “I lived under communism, that was uncontrolled power – and unchallengeable power. This should not happen in any EU member state,” she said in an interview with Investigate Europe, a co-operative of journalists from different European countries. Media are “the ones who keep politicians under control. If we want the media to fulfil its important role in democracy, we have to introduce a European safety net.” That is why she is pushing to implement a landmark EU law “to protect media pluralism and independence”, which would set legally binding standards to preserve press freedom in all EU member states.

She and her colleagues introduced the bill in September 2022. Among other things, it provides that: public service media must report “impartially” and their leadership positions must be “determined in a transparent, open and non-discriminatory procedure”; the allocation of state funds to media for advertising and other purposes must be made “according to transparent, objective, proportionate and non-discriminatory criteria”; governments and media companies must ensure that the responsible “editors are free to make individual editorial decisions”; owners and managers of media companies must disclose “actual or potential conflicts of interest” that could affect reporting; and the enforcement of journalists to reveal their sources, including through the use of spyware, must be prohibited.

All of this seems self-evident for democratic states and yet it met with massive resistance from not only Hungary and Poland, but also Austria and Germany. They argued the proposal is overreaching, “with reference to the cultural sovereignty of the member states”, according to minutes from the legislative negotiations in the EU Council, obtained by Investigate Europe. The four governments wanted a directive rather than a legally binding regulation, which would allow the governments to undermine the bill.

In Germany, media supervision is the task of regional states. On their behalf, Heike Raab from the state government of Rhineland-Palatinate, led the negotiations in the EU Council. The EU was acting as a “competence hoover in an area that was expressly reserved for the member states in the treaties”, Raab argued, saying the law would be an “encroachment on publishers’ freedom” in line with the respective lobby. If publishers are no longer allowed to dictate the content of their media alone, this would “destroy the freedom of the press”, the Federal Association of Newspaper Publishers declared. The European Publishers Association claimed that the EU proposal was in fact a “media unfreedom act”. However, Raab and the publishers’ lobby failed to present any practical proposals on how to stop the attacks on editorial freedom.

Such opposition has so far proved largely unsuccessful. Although several controversial amendments to the law have been put forward (most notably when a majority of EU governments backed a change to allow the possible use of spyware in the name of national security), the key proposals of Jourová and her colleagues were adopted in June by most EU governments. If, as expected, the parliament also gives its approval at the beginning of October, the law could come into force early next year – and trigger a small revolution in the European media system. At least that is what Jourová hopes.

The direct influence on public service media by way of appointment of politically affiliated managers, as seen in Greece and Italy, for example, would not be compatible with the new law. “The state must not interfere in editorial decisions,” Jourová said. If a member state does not comply, the Commission could open proceedings against the government for violation of the EU treaties. And if the violations continue, this could “lead to very serious financial penalties from the European Court of Justice.”

Journalists themselves could also sue governments or private media owners in national courts against censorship or surveillance on their part, the Commissioner explained.

It is questionable, however, whether this can help reverse the decline of media diversity in the right-wing populist-ruled countries. The Hungarian and Polish government are already accepting the blocking of billions in payments from EU funds because they violate the principles of the rule of law with their political control of the courts. So why should they fear further rulings by EU judges?

Viktor Orbán’s regime has for years engineered a “creeping economic strangulation” of independent media in Hungary, says journalist Zsolt Kerner of the online magazine 24.hu. The government withdrew all state advertising contracts for independent media and then pressured commercial advertisers to do the same. Today, advertising revenues only go to media loyal to the government. 24.hu survived only thanks to an economically strong and independent investor. The rest either had to close or were taken over by those connected to Orbán. This would all become illegal with the planned regulation because EU law trumps national legislation. But Kerner and his colleagues “doubt whether it will do any good in our country.” After all, the government has “many good lawyers”.

“Maybe Hungary is a bit immune now,” said Commissioner Jourová. But there, too, the government will “sooner or later feel the political impact”. An “independent European media board”, including media experts from all 27 EU states, is planned under the new regulation. While the board can decide by majority vote only on assessments without legal consequences, Jourová expects that countries “which the board certifies as restricting media freedom” will “lose their international reputation, for which most governments are very sensitive.”

This could well put pressure on the right-wing nationalists in Poland, thinks Roman Imielski, deputy head of Gazeta Wyborcza, the country’s last major independent newspaper. Prime Minister Mateusz Morawiecki’s government has also turned public television and the national news agency into “a Russian-style propaganda machine” that brands all critics as “traitors to the nation and conspirators”, Imielski said. But if Poland looks bad to the US government, for example, “that puts pressure on it”, as happened when the government tried to sell the government-critical TVN station, owned by a US group, to a Polish buyer. Under pressure from Washington, the Polish president vetoed the corresponding law in 2021.

When or even if Jourová’s grand plan actually becomes law is still unknown. After the parliamentary adoption scheduled for the beginning of October, its representatives still have to agree on a common text with the Council. As mentioned, most EU governments want to reverse the planned ban on the use of surveillance software against journalists and explicitly allow it in cases of danger “to national security”. Article six, which obliges media owners to respect “editorial freedom”, is also highly controversial. Member states, including Germany, want to weaken this provision considerably by only granting this freedom “within the editorial line” set by media owners. If successful, the law would fail at a crucial point.

“The problem is not media concentration in itself, the problem is that it gets into the wrong hands,” said Gad Lerner, a columnist at the still independent Il Fatto Quotidiano, who worked for La Repubblica until it was sold. “More and more entrepreneurs with a core business in other industries are buying newspapers, TV or radio to give visibility to the politicians on whom they depend for their real business.”

“Of course, we don’t want rich people to buy media to influence politics. But we are not here to micromanage how the newsrooms should be organised,” Jourová said, pointing to the need for civil society and journalists to help push for stronger editorial freedoms.

The Greek journalist Sofia Mandilara, who works at the state news agency, has already given a starting signal for this. With the help of the trade union, she filed a public complaint against the censorship of statements critical of the government in one of her articles and – to her surprise – was allowed to write another article on the subject. Since then, “at least they always ask me when they want to change my texts,” she said with a laugh.

This is a modified version of an article that first appeared on Investigate Europe here