[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Africa & Argentina, the June 1980 issue of Index on Censorship magazine

By Ahmed Rajab

We devote a large part of this issue to dissent in literature and the arts in Africa, and the response to it by the ruling circles in a number of countries. This may seem an ambitious project

in the sense that Africa is not a homogeneous whole but a continent with different social systems, beset with a high degree of illiteracy, a multitude of languages and a variety of cultural practices.

There is another sense, however, in which Africa as a whole can be discussed under this one rubric: the artist in almost all the African countries is viewed with suspicion the moment he takes on the role of a social critic. This despite the fact that traditionally, whenever a poet or a dramatist acted as a social critic and a ‘ chronicler of current events ‘, he was protected by society, the tribe. The earlier griot of West Africa or the Swahili poet of East Africa, could indulge in criticism of the social order without undue worry about the consequences — the more so if his views were shared by the rest of his community. The eighteenth century Kenyan coastal poet Muyaka wa Muhaji was famous for his impromptu improvisations of anti-establishment poetry. Cultural activists were more than just individual performers; they acted as the eyes, ears and mouthpieces of their societies. Although griots were originally the spokesmen of local kings, whom they spent days praising, they later extended their role to that of historians and commentators on history. In some parts of Senegambia they are known to have been responsible for bringing down a number of tribal chiefs. They were the conscience of society; they were there to see that society functioned as it should, and if it didn’t they tried to put things right. Not that everybody, rulers included, agreed with them. But if they did not, then their poetic broadsides were answered by other poems defending what the original poems or songs attacked. Rich powerful families instead of engaging in physical warfare with their enemies would send their griots to fight with ‘words’ the griots of their rivals.

Nowadays if a poet, novelist or playwright incurs official displeasure, he will almost invariably be arrested and imprisoned, as happened to the Kenyan Ngugi wa Thiong’o, or be permanently silenced as was the case with the Ugandan playwright Byron Kawadwa. If he is lucky, the dissident writer may escape to another country, and die in exile, like the Guinean novelist Camara Laye.

Colonialism has a lot to do with the present predicament of the artist in post-colonial Africa. Not only did colonialism subjugate the culture of the colonised by imposing its own cultural hegemony in order to facilitate colonial rule, but it also used state power to suppress anti colonial dissent as expressed in the performing arts. With slight modifications, the same coercive instruments of state are now being employed by post-colonial African governments to suppress any anti-establishment critique offered by the arts. The situation is the more serious because, in the absence of a legal opposition in most of these countries, literature and the arts provide the only platform for nonconformist ideas.

It is the ruling circles in these countries which seek to monopolise the ‘ right and correct’ ideas. Ideas that are judged to be hostile are viewed as subversive. The performing arts are also regarded as dangerous once their thematic preoccupations are not acceptable to the ministries of ‘ national’ culture that have sprung up after independence in almost all the African countries.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column width=”1/4″][vc_icon icon_fontawesome=”fa fa-quote-left” color=”black”][/vc_column][vc_column width=”3/4″][vc_column_text]

In fact, it is the gradual thematic shift in literature and the arts from historical self-glorification to contemporary socio-political realities that has been responsible for increasing official intolerance towards them. But it is an aspect of totalitarianism not to tolerate dissenting views, be it in South Africa under the apartheid system or in any of the many one-party states of black Africa.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

The comparison may not be altogether fair, but the very fact that one can talk of such a comparison sheds a poor light on those countries that have for decades championed the cause of political freedom, free expression of ideas, freedom of association, and human rights in general for colonised Africa.

Admittedly the human rights situation has improved in a number of African countries in the past year. The Organisation for African Unity has recognised the urgent need for the establishment of a Commission on Human Rights for Africa, and there has, in general, been an increase in the awareness of human rights in connection with national development. But although Ngugi wa Thiong’o was released from prison in Kenya, a number of writers and poets are still incarcerated in South Africa and Morocco. In fact, Morocco is the only independent African country with a high number of writers and poets among its prison population. It is not irrelevant, of course, that in a country which supposedly has a multi-party democracy, no opposition party can be legalised without King Hassan’s assent. Those who operate outside the permitted limits are regarded as a ‘ danger to the security of the State’. The same could be said of Egypt, where President Sadat created his own opposition party and forced no less than 220 members of his ruling party to join it. The Egyptian dissident poet, Ahmed Fouad Negm {see Index on Censorship 2/1979 and 2/1980) is still on the run, evading the police. Egyptian journalists who disagree with President Sadat, even those working in the institutionalised press, have been silenced. In Senegal, it is no less a person than the enlightened poet-President Leopold Sedar Senghor, who saw fit to determine how many opposition parties, and of what nature, he was willing to tolerate. And it was Senghor who banned a film by the noted film-maker, Sembene Ousmane, ostensibly because he disagreed with the spelling of the film’s title (see Index on Censorship 4/1979, p. 57). The situation of the arts and literature in Africa could be comical but for its tragic consequences.

We have tried in this issue to portray some aspects of the difficult situation in which the writer and artist operate in the continent. Although there is these days a tendency to separate North African literature and culture from the rest of Africa, we do not apologise for including them. After all, the very name ‘Africa’ originated from that part of the continent. More important is the fact that the predicament of the writer in North Africa is no different from that of his colleagues south of the Sahara. They live subject to the same fears, and they share the same dreams and the same hope:of being free to operate as artists.

As far as the overall situation is concerned, the picture that emerges from these pages is sobering. But we can still hope that respect for human rights will continue to rise in the continent, and that the artist and writer will eventually be accorded his freedom. In the meantime, dissident artists, if not murdered, continue to be imprisoned, exiled, or silenced by self-censorship.

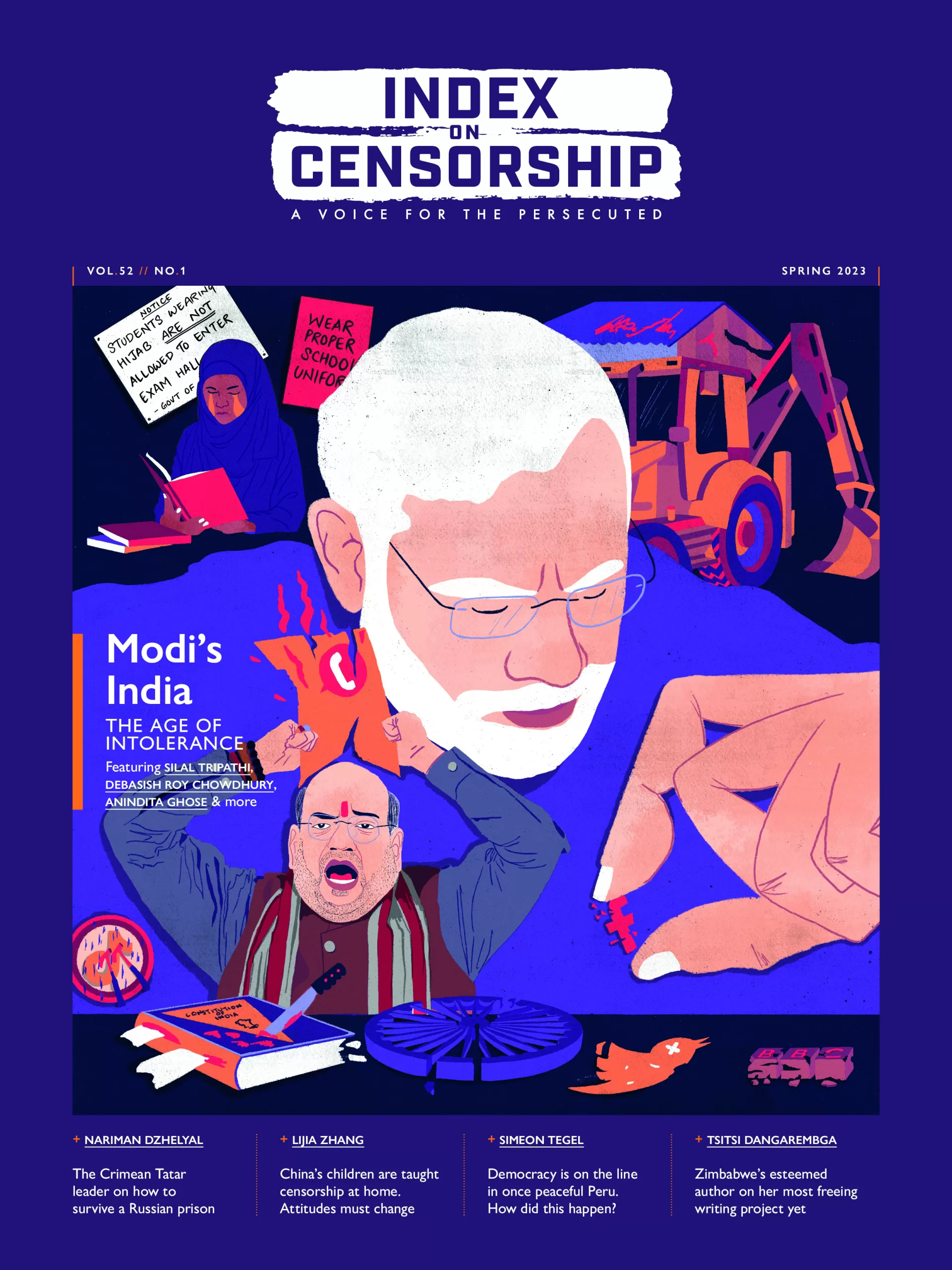

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_single_image image=”93828″ img_size=”full” onclick=”custom_link” link=”https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1080/03064228608534038″][vc_column_text]

Africa — silent continent?

The oral tradition provides outlets for dissent which have been

blocked by today’s rulers.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_single_image image=”94326″ img_size=”full” onclick=”custom_link” link=”https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1080/03064228108533251″][vc_column_text]

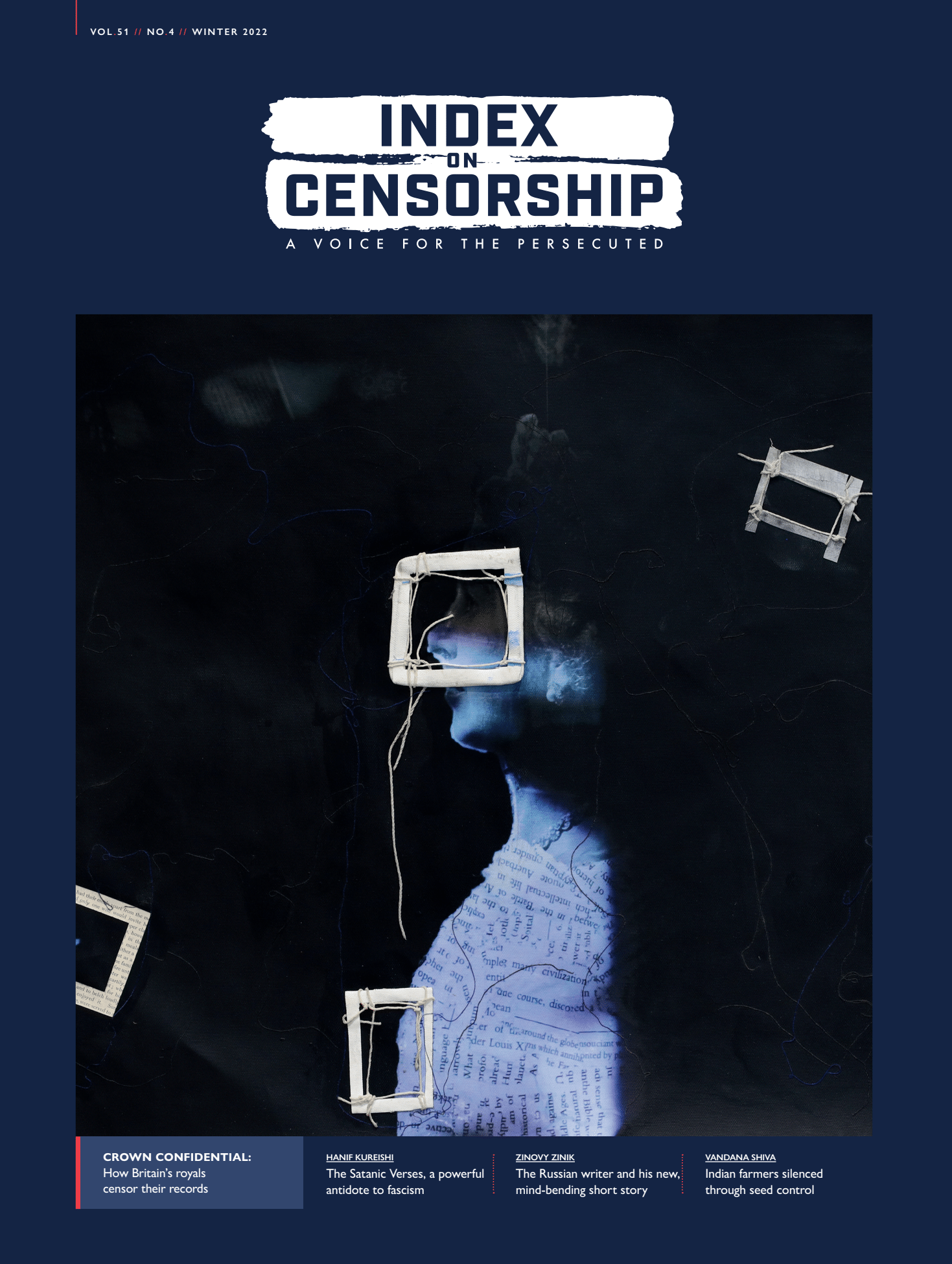

No place for the African

South Africa’s education system, meant to bolster apartheid, may destroy it[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_single_image image=”93873″ img_size=”full” onclick=”custom_link” link=”https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1080/03064228508533914″][vc_column_text]

Namibia: How South Africa controls the news

If you think censorship is tough in the Republic, take a look at the

manipulation of information in its colony.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]