[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

UNESCO’s threat to press freedom. the February 1981 issue of Index on Censorship magazine

By Hugh Lunghi

Over thirty years ago, in 1946, the United Nations solemnly resolved that ‘freedom of information is a fundamental human right and the touchstone of all the freedoms’. The newborn UN Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organisation promised ‘to promote the free flow of ideas by word and image’.

Last November the 154 UNESCO member states enjoined the Organisation to define and create a ‘new world information and communications order’. There are in the world barely a score of states where the press can be considered free. Paradoxically, governments with a virtual monopoly over information in their countries have complained most loudly of the developed nations’ monopoly of world information, demanding a new ‘order’.

Two issues have become, deliberately it seems, intermingled: first, the imbalance between developed and developing countries’ communications resources, symbolised by the ‘Big Four’ news agencies; secondly, whether journalists should be free to report without regulation or whether states should instead use the media for various national purposes.

At the 1970 and 1972 UNESCO conferences Soviet delegates proposed telling governments to ‘forbid’ use of the media for propaganda purposes on behalf of war, racialism and hatred among nations, leaving governments to decide what constituted such propaganda. The resolutions sought to justify the closing down of news sources, especially non-communist radios, unpalatable to Soviet bloc countries. After years of argument a modified resolution was presented to the 1976 UNESCO conference in Nairobi.

The resolution contained a great deal about the ‘ duties’ of the mass media, nothing about the free flow of information within nations. The International Press Institute, with its long record of supporting journalists in exposing racism, apartheid and war propaganda, warned that the ostensibly laudable objectives could be used to sanction controls on the media detrimental to the free flow of information. UNESCO had turned its attention to devising rules which could limit that freedom. To meet such criticism UNESCO set up, in 1977, a Commission under former Irish Foreign Minister Sean MacBride, a Nobel and Lenin Prizewinner.

In 1976 a Non-aligned Countries’ summit conference in Colombo had addressed itself to the North-South imbalance in communications resources. The imbalance and the Third World resentment was recognised by journalists, news agencies and governments in the developed world. Practical help in training, equipment and funds amounting to several million pounds worth, have been extended to Third World journalists.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column width=”1/4″][vc_icon icon_fontawesome=”fa fa-quote-left” color=”black” size=”xl” align=”right”][/vc_column][vc_column width=”3/4″][vc_column_text]

Governments and their UNESCO officials are not satisfied to leave practical help and responsibility for fair and accurate reporting in the hands of journalists and editors.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Indeed UNESCO has greatly reduced its practical help to third world media. UNESCO debates have shown that some governments simply believe that people should be told only things about which they ought to care. Other governments simply do not like any reporting at all of ‘corruption, coups and calamities’, as was demonstrated so vividly during the latest UNESCO conference by the arrest of a French news agency man in Zambia for reporting, accurately as it proved, the threatened coup against President Kaunda’s government.

The crucial debate between the concept of a free press and the press as a tool of government

will be formally resumed by UNESCO. This number of Index on Censorship is largely devoted to the document on which the debate is based – the report of the MacBride Commission. It is criticised by Frank Barber, whose work as foreign correspondent for the liberal daily News Chronicle and others, including the BBC, embraced many Third World countries.The other major article on the subject is by Raphael Mergui, a Moroccan journalist writing for Jeune Afrique. We hope readers, whatever their views, will respond.

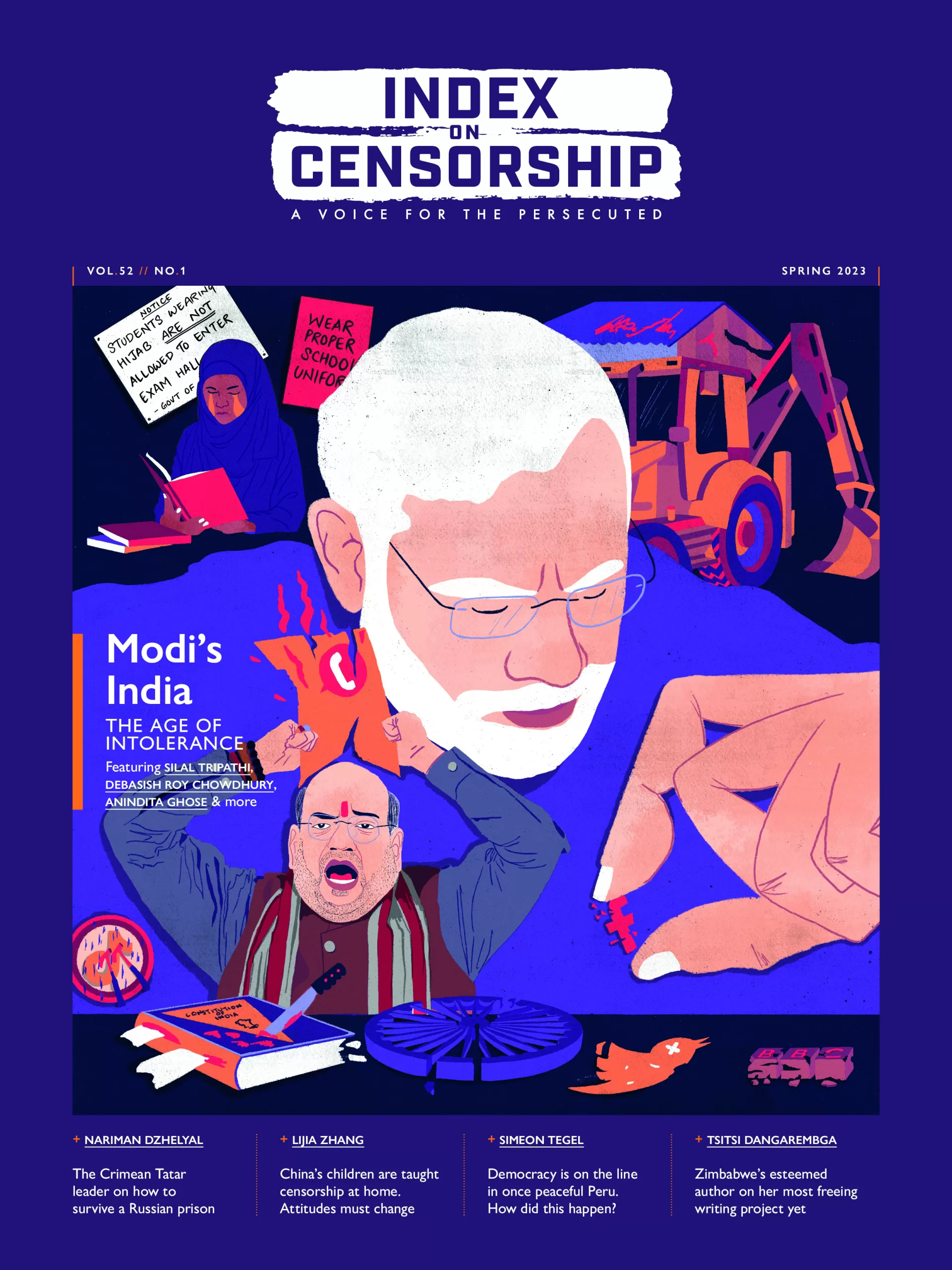

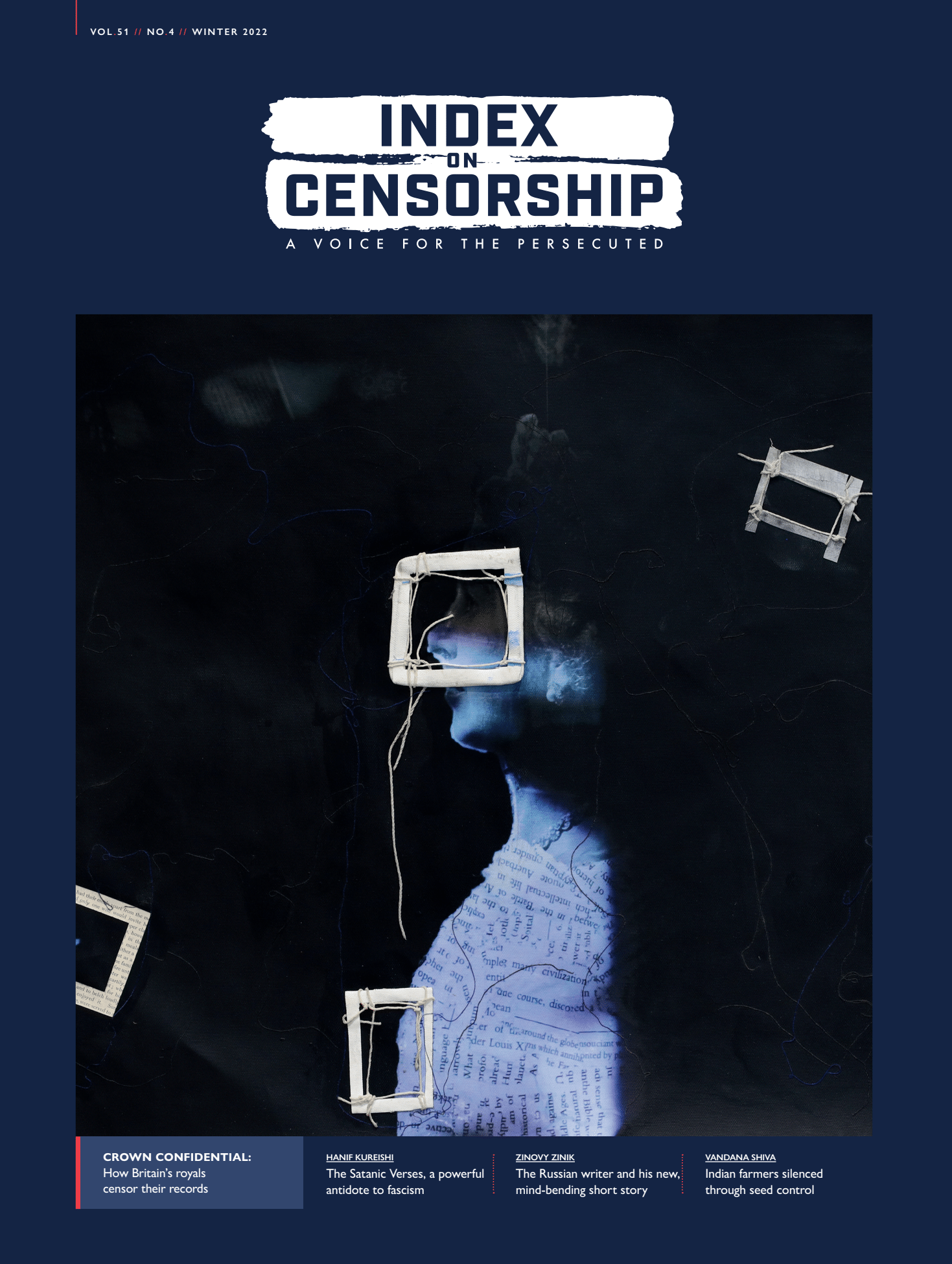

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_custom_heading text=”What price protest?”][vc_column_text]The winter 2017 Index on Censorship magazine explores 1968 – the year the world took to the streets – to discover whether our rights to protest are endangered today.

With: Ariel Dorfman, Anuradha Roy, Micah White[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_single_image image=”96747″ img_size=”medium”][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_column_text]In print, online. In your mailbox, on your iPad.

Subscription options from £18 or just £1.49 in the App Store for a digital issue.

Every subscriber helps support Index on Censorship’s projects around the world.

![]() SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]