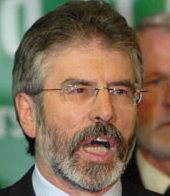

Gerry Adams and Sinn Féin are trying to stifle debate in Belfast’s media, writes Anthony McIntyre

Gerry Adams and Sinn Féin are trying to stifle debate in Belfast’s media, writes Anthony McIntyre

Gerry Adams of Sinn Féin is the current Westminster MP for West Belfast. For decades he rightly campaigned against censorship policies crafted by successive British and Irish governments for the purposes of undermining his party. British readers may recall him as the only member of the House of Commons they could see but not hear. On each occasion that he appeared on TV over a six-year period from 1988, an actor’s voice was used to dub his words. On radio he was neither seen nor heard, the dubbing procedure again in play. It was only one of a range of draconian measures applied to silence him and his party. Former Irish Journalist of the Year Ed Moloney has repeatedly asserted that such censorship prohibited dialogue and consequently prolonged Northern Ireland’s violent conflict.

Although a victim of harsh political censorship, Adams’ disinclination to use this invidious tool of political repression has been less than salutary. Never a figure at ease with even the mildest form of political criticism, he has persistently sought to undermine those who do not see the world through his eyes and who are prepared to voice their misgivings publicly. Virtually everyone who has left Sinn Féin since the signing of the Good Friday Agreement a decade ago has highlighted the suppression of debate among their reasons for quitting. Adams has no record of speaking out against those murdered, kidnapped or beaten by his party’s military wing simply because they chose to dissent from his political project. On occasion Adams has hit out at those daring enough to have a public ‘poke’ at his leadership. Elsewhere he has been on record saying that people should not be allowed to even think that there is any alternative to the Good Friday Agreement. There is no concession to the idea that without audacious thinking, West Belfast intellectual life would be even more restricted than it currently is.

Yet even this track record ill prepared a wider audience for his and his party’s response to an admittedly blistering critique launched against him by Robin Livingstone, editor of a twice-weekly paper in his own constituency, the Andersonstown News. Livingstone, writing under his publicly known pen name ‘Squinter’, was scathing of Adams’ record as MP. He traced the economic decline of the constituency and the onset of its social decay to Adams first taking the Westminster seat in 1983.

The immediate backdrop to the Livingstone piece was the vicious murder of a popular former republican prisoner, Frank McGreevy, savagely bludgeoned to death in his own home. Livingstone, obviously incensed at the brutality of the killing, called upon Gerry Adams to accept responsibility for the problems blighting West Belfast, including criminality, rather than continuously resort to type and blame everybody else.

Despite a lengthy career as a journalist, Robin Livingstone had not been associated with criticisms of the Sinn Féin leadership either in public or private. It was the first cut he had ever made. The first, they say, is always the deepest. The depth to which he had penetrated was evident in the response, for which he was seemingly unprepared.

Sources with some knowledge of the dispute claim that shortly after the paper hit the streets Gerry Adams rang the Andersonstown News and berated Livingstone for 30 minutes, thus flouting his own public pronouncement on the BBC that he would not respond to ‘anonymous scribes’. At a vigil for the murder victim the former Sinn Féin mayor of Belfast, Alex Maskey, hit out at people who hid behind their computers writing. At the subsequent funeral Gerry Adams fulminated against the ‘quite perverted logic’ of the piece in question. It was then reported that business interests in West Belfast with links to Sinn Féin threatened to withdraw advertising from the Andersonstown News in response to the criticism of Adams. A leading figure in a West Belfast Sinn Féin branch told Livingstone in print: ‘How dare you? … you will no doubt be challenged on these ill-conceived remarks in coming weeks by a very angry community.’

All of this mounted to a standard totalitarian attempt to subvert public commentary. It is entirely consistent with authoritarian regimes throughout the globe which prefer to impose silence out of public view rather than stage debate within it.

Within a week of the article appearing, the Andersonstown News carried a front page apology from the editor to Adams for the ‘hurt’ caused. The psychological pressure applied to secure a front page apology, a rarity in the world of media, must have been considerable. Since then the ‘offending’ column has been removed from the paper’s website and from Livingstone’s own newspaper-affiliated blog, along with all readers’ comments. It is far from clear that Livingstone, apparently out of the country at the time of the printed apology, assented to it appearing. The famous dogs of the West Belfast streets opine that Livingstone was overruled in a managerial act of sycophantic subservience.

Gerry Adams had the opportunity to kick start a serious dialogue about the Livingstone claims. Rather he has sought to impose the Sinn Féin monologue as the only approved element of political discourse that the constituency is to host. Adams could easily have acquired a two-page right to reply in which he would have been free to address in a detailed manner the points raised. Whether right in his assertions or not, Livingstone had merely given vent to views in the constituency. But rather than challenge Livingstone, Sinn Féin opted for his public humiliation, forcing an editorial apology for an article so finely crafted that it is beyond belief that it was rush of blood to the head for which public expiation is the sole cure.

In a society already subjected to government minus any official opposition, what has happened to the editor of the Andersonstown News is deeply alarming. It is a censorious assault on free inquiry.

One irony in the affair is that Robin Livingstone for long did to others what is now being done to him. He incessantly waged invective against those who criticised the Sinn Féin leadership and denied a right to reply to those maligned in the paper he edited. Many people felt intimidated to the point of silence by the power of the Andersonstown News under the editorship of Livingstone. Nevertheless, it would be churlish to deny the remarkable courage he displayed in a constituency where Mugabe rather than Mandela would appear to be the current icon. Furthermore it would be dangerous to indulge in schadenfreude at Livingstone’s current predicament. He did what journalists are supposed to do — asked the awkward questions, and in so doing performed a valuable act of public service. For that reason alone his action in writing the column deserves the support of everyone who thinks society should know more rather than less about how it is governed.

Sinn Féin’s assault on a fundamental civil liberty demands a response that must be unyielding in the face of totalitarian sentiment.

Anthony McIntyre blogs at The Pensive Quill