The censorship of an exhibition in Sydney says more about the infantilising impulse of the authorities than it does about art, says Binoy Kampmark

The censorship of an exhibition in Sydney says more about the infantilising impulse of the authorities than it does about art, says Binoy Kampmark

‘A barrier of illiterate policemen and officers stands between the tender Australian mind and what they imagine to be subversive literature’

HG Wells

Art exhibitions can be a hazardous business, especially in Australia. Australia was, at one time, banning more art and literature coming in than going out. The only thing the authorities did not do was burn books and slice canvasses. In terms of ‘western’ democracies, only Ireland pipped Australia to the post of conservative, censoring hysteria.

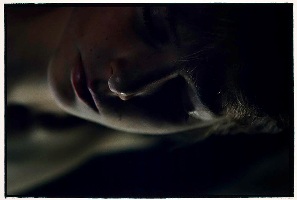

The work of photographic artist Bill Henson has been added to this registry of ‘indecencies’ that have troubled the Australian conscience. Twenty Henson photographs featuring ‘naked children aged 12 and 13′ were confiscated on 22 May from the Roslyn Oxley9 gallery in Sydney.

The police are proving rather enthusiastic in prosecuting the case. Victoria’s Assistant Commissioner Gary Jamieson, fancying himself as budding art critic, promises to ‘go through the process of evaluating those works’.

Galleries are being hounded into removing pictures by the new moralists. Some are digging in for the moral onslaught. The Monash Gallery of Art is backing Henson, who, in the words of its director, Jason Smith, ‘has consistently explored human conditions of youth, and examined a poignant moment between adolescence and adulthood’.

Everyone is a judge in a democratised art world. But the power to judge is not always proportionate with the power to act on it. At most, disgusted citizens can either stay away, switch off the screen or walk out. Thankfully, they don’t have the power to deprive a gallery of its liberty.

Not so the police, whose judgments often resemble the mediations of a belligerent philistine. This police drive is all tied up with the mentality of the censor. The censor is not only dismissive of reality, but genuinely repelled by it. Poet Max Harris provided the ideal summation: ‘The law is framed, and prosecutions are carried out, to prevent us from knowing the facts of life, the state of the world, the realities.’

Child protection in the Henson case provides an apt metaphor: Australia is itself an innocent, a child in fear of growing up. Dream and for heaven’s sake don’t get carried away with thoughts of what really happens. ‘Kids deserve to have the innocence of their childhood protected,’ argued Prime Minister Kevin Rudd. He also found the images ‘revolting’. Australians should, of course, be deprived of seeing films and other media that might sunder their tender minds. Seeing Henson’s works is bound to turn us all into drooling deviants.

The moral tick that underlies such reactions is tediously consistent with Antipodean history, from religious activist Rona Joyner to the Office of Film and Literature Classification. The OFLC made hay under the Howard government, targeting such films as Ken Park and Baise Moi as inconvenient unforgivable intrusions of reality upon the Australian public. Ken Park was fatally flawed for depicting gratuitous child self-abuse and fetishism in what were ‘high impact scenes’ — the Australian public had to be shielded from the cruel depictions — after all, children don’t really behave like that. Surely not.

Different standards apparently apply, because of a child’s innocence and fragility. How such innocence is defined is, of course, highly arbitrary. A society apoplectic at the very mention of sexualised children is incapable of finding a balanced approach, and the reaction to Henson is a case in point.

Children are the noble savages of modern consciousness, deified, put on pedestals, and, as a result, beyond understanding. Adults are presumptively evil; children, the untarnished good. There is a little irony in this, as Henson has himself described his child shots as exploring ‘something which is absolutely inviolate and unknowable’.

Others are more subtle about their condemnation, adding a gleam of polished ignorance to their assessments. Children should not be prematurely sexualised, argues Victoria’s Child Safety Commissioner Bernie Geary. (Since when haven’t children been prematurely sexualized?) No more nymphets on canvas, thanks. Farewell to the Bronzinos and the Egon Schieles, which depict the advances of child figures on older women, all dismissed as the vulgar, suggestive extravaganzas of sexualised minors.

Presumably, all art, notably art that portrays children in ‘suggestive’ ways, must suffer the same fate — after all, art has itself become a commercialised marketplace phenomenon, a capitalist binge.

The police involvement, and Rudd’s moral venting, brings to mind the debate between the British legal scholar HLA Hart and his sparring counterpart, Lord Patrick Devlin, on morality’s role in the law. For Hart, citing the opposing view of the Wolfenden Report (1957), the law should resist enforcing moral precepts unless they involve acts which cause genuine harm to individuals. This is vintage John Stuart Mill.

Devlin demurred, citing the familiar argument that an assault on ‘constitutive morality’ would degrade society in due course. It seems very unlikely that the public, let alone children, need to be protected from Henson and his pictures. The police and Rudd think otherwise.

If the police are so keen on protecting a vulnerable public from itself, they might start with cleansing Australian galleries of Norman Lindsay’s work, with its saccharine depictions of flesh that don’t so much sigh as sag. When the British art critic Sir Kenneth Clark cast his eye over Lindsay’s canvasses on a journey to Australia, he exclaimed that he had never seen such a vast collection of Victorian pornography in his life. Criticism of Henson should only be that of the man as artist. If vulgar, then so be it. It is certainly harmless, and hardly indecent.

Binoy Kampmark was a Commonwealth Scholar at Selwyn College, University of Cambridge. He is currently lecturing at the University of Queensland