The latest high-profile, UK privacy case raises critical questions for press freedom, writes Jo Glanville

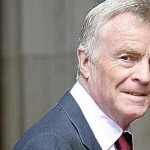

The ruling on the Max Mosley case has turned out to be less chilling for free speech than originally feared. Mosley, the president of FIA, Formula One’s governing body, has successfully sued the News of the World for invading his privacy, but he was not awarded the ‘exemplary damages’ he was seeking. So while the damages he will receive of £60,000 may be the highest award yet in a privacy case, it is not the kind of sum that will deter the press from reporting similar cases in the future.

The News of the World had arranged for Mosley’s sadomasochistic sex exploits to be secretly filmed and had then accused him of engaging in a ‘sick Nazi orgy’. The judge did not accept the argument that publication was in the public interest. Yet the ruling does not mean that all public figures in the future can rest easy that their particular pecadilloes will be safe from press intrusion. If it had been a politician or business leader whose sexual antics were under scrutiny, then it’s less likely that the judge would have been able to rule that it was not in the public interest. It was, after all, Justice Eady who ruled that the Mail on Sunday could publish its revelations about John Browne, the head of BP, last year.

Yet there are a number of critical questions here for press freedom in the UK. In the first place, the question of defining what is in the public interest. Justice Eady drew attention to the risks Max Mosley was taking by engaging in conduct that could expose him to blackmail: ‘it might seem that the claimant’s behaviour was reckless and almost self-destructive’. This view of Mosley’s behaviour influenced the level of damages the judge awarded him. Yet there is surely an argument that such ‘reckless and…self-destructive’ behaviour in the president of FIA, the motorsport world’s governing body, should be in the public interest: it raises questions about his judgment.

Justice Eady has come to be known as the ‘privacy judge’. When the European Convention on Human Rights became part of English law eight years ago, the UK found itself with a privacy law for the first time and Eady has taken on many of the cases. In his judgment yesterday, he showed himself to be a little sensitive to such criticisms: ‘It is not simply a matter of “unaccountable judges” running amok,’ he wrote. ‘Parliament enacted the 1998 statute which requires these values to be acknowledged and enforced by the courts.’ He is right, but what is a concern is that there are too few judges taking on these cases and that there needs to be a wider pool of experience making rulings on such a new area of the law.