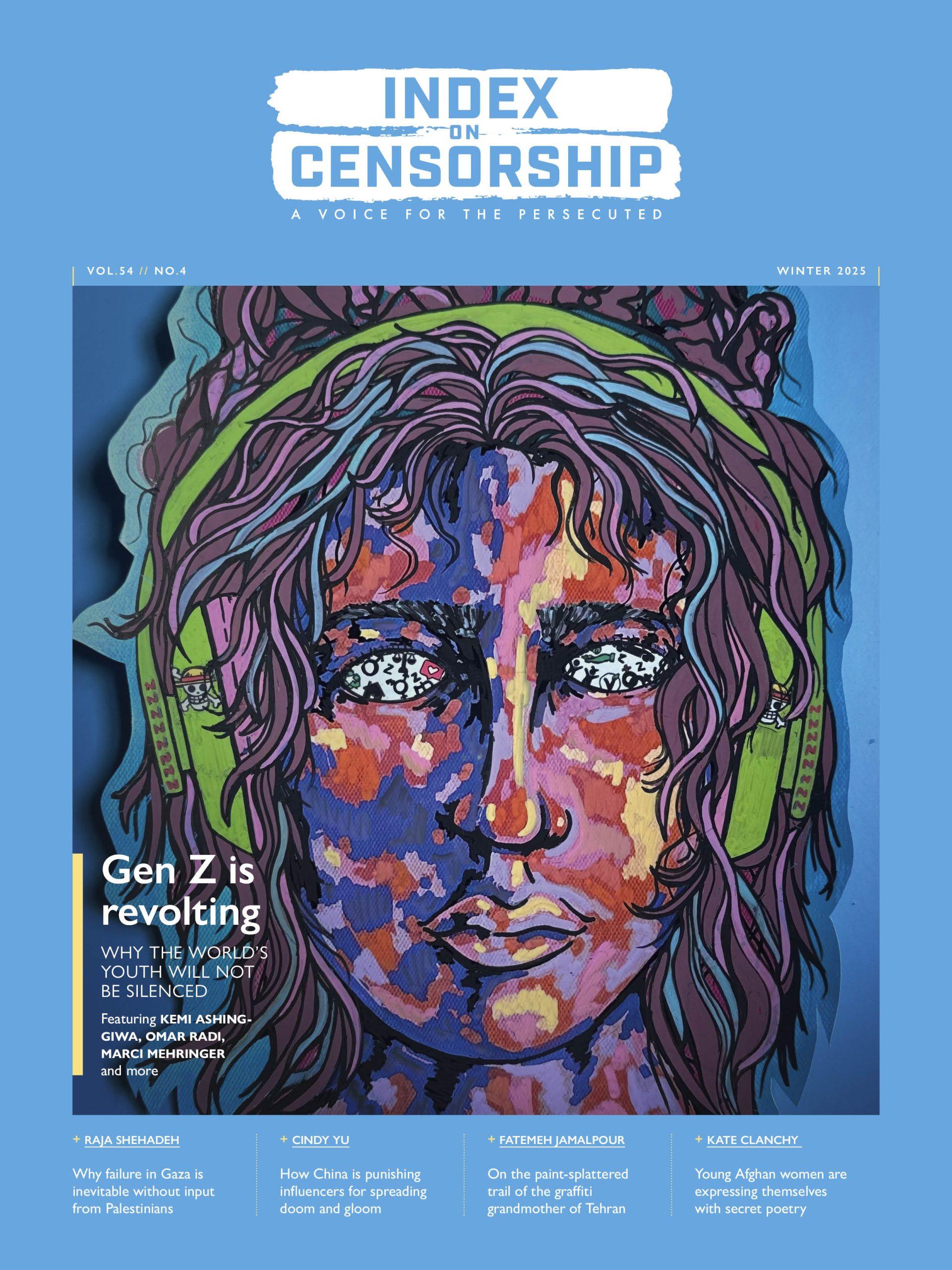

Harassment of reporters such as Sihem Bensedrine (right) shows that Tunisia leads the way in suppression of free expression, writes Rohan Jayasekera

Harassment of reporters such as Sihem Bensedrine (right) shows that Tunisia leads the way in suppression of free expression, writes Rohan Jayasekera

There’s an old proverb that ‘a lie can get halfway round the world before the truth has got its boots on.’ As free expression campaigners we are used to governments sponsoring disinformation and lies to discredit critics. Every country has a few state-run or government-favoured publications willing to run lies on their behalf. What’s new is the scale of these disinformation operations, which now spread to the planting of news, adverts and paid-for editorials in foreign papers as well as the local press.

The most brazen practitioner of this kind of propaganda is Tunisia, which has unleashed a storm of such material at home and abroad, in reaction to the way its record of human rights abuse is being exposed internationally.

In December a French court found Tunisian ex-diplomat Khaled Ben Said guilty of torture and sentenced him in absentia to eight years jail. Days later a leading witness for the prosecution, journalist and free speech campaigner Sihem Bensedrine, found herself the target of a major propaganda attack. Bensedrine is the winner of a number of international awards for her human rights work in Tunisia. But her magazine Kalima is denied a license and its website is blocked. Bensedrine has been jailed and beaten by security forces and viciously insulted by the pro-state media for her stand in the past.

Indeed, when it cannot jail its critics, Tunisia has tried threatening or beating them. It has tried bribes and enticing job offers; or it has tried intimidating their families, tried locking critics into endless legal action, tried slandering them in paid adverts, tried bugging their Internet and blocking their sites; and the authorities have tried barring their opponents from travel.

Index on Censorship magazine studies the ways of state censorship all over the world and nowhere else but Tunisia are journalists and human rights groups targeted in so many diverse and devious ways. It’s almost impressive. If only all that effort and ingenuity was put to more positive use.

It’s needless to refute the propaganda, which conjures up figures and false claims about Bensedrine’s relationships with international donors. Her donors and partners are on public record; they will confirm that the due diligence required of them as partners shows nothing to give them concern. The state-owned, state-sponsored or state-favored news organizations that recycled the rubbish about Bensedrine did not check the information. What is surprising is that foreign news organizations – including some with distinguished histories – have allowed themselves to become complicit in this strategy.

Last week, media rights groups in France, Norway, Switzerland and the United Kingdom complained to the global news agency United Press International for republishing the false allegations. They urged UPI ‘to protect its reputation by making appropriate amends, and for the agency to take steps to ensure it is not embroiled in this kind of state disinformation again.’

In Egypt the pro-government daily Rose al-Yousef was widely criticized at home and abroad for publishing a quarter page advertisement filled with more false allegations defaming Bensedrine, and topped it with a photo of Tunisian President Zein al-Abedin Ben Ali.

‘We are used to these campaigns and attacks being waged against us,’ said 19 Egyptian human rights groups in a joint statement. ‘However, what angers us is how they tarnish the name of a once great media institution that through the pioneering work of journalists such as Salah Hafiz, Kamil Zehairi and Hassan Fouad helped to create freedom of the press in Egypt.’

Carelessness and unprofessionalism have turned once respectable newspapers into tools to damage the reputations of brave journalists and activists.

Tunisia is not alone in seeking to take advantage of journalists willing, for whatever reason, to relax their professional standards of impartiality and balance. This strategy of blurring the lines between truthful reporting, unattributed opinion and propaganda, coordinated to serve a political objective, is also being extensively developed by the United States in Iraq, despite domestic legal restraints and strong ethical opposition.

But the reality is that the responsibility of separating truth from lies rests where it always has: on the shoulders of journalists. They should treat false reports with healthy skepticism and always question the motive behind the message. In today’s high-volume, high-speed media environment it has never been more important to ask not only ‘Is this person telling me the truth?’ but also to ask ‘Why is he telling me this?’

Rohan Jayasekera is associate editor of Index on Censorship and chair of the Tunisia Monitoring Group (TMG), a coalition of 18 member organizations of the International Freedom of Expression Exchange (IFEX) network.

This article was originally published in the Lebanon Daily Star