International recognition offers a degree of protection to investigative reporters. But, writes, Lydia Cacho being in the limelight presents a new set of dilemmas

International recognition offers a degree of protection to investigative reporters. But, writes, Lydia Cacho being in the limelight presents a new set of dilemmas

Translated by Amanda Hopkinson

The first call is the one you never forget. The person uttering the death threat has spent days preparing for this moment — to let you know that your fate is sealed. Up until this phone call, threats were something ethereal and alien, something that happened to other people.

Over time, I learned a lesson that many journalists and writers have learned before me: that becoming the news is a double-edged sword. It can weaken and wound. It unsettles us and sets us apart from our colleagues and loved ones. The threats become as important as the original story.

This dilemma dominates the rest of our lives, because for us to come through safely we need to be out there, in public, and never be silenced. At the same time, we have to remain on guard, watching our backs, alert whenever we see a police or military patrol, reacting instantly to any sound resembling a shot, tensing every time a motorcycle accelerates or approaches, permanently on the look out for a weapon in case the rider is a hit man. And on and on, we have to proclaim to the four winds, until we’re fed up with doing so — and everyone else is fed up with us too — the name of the Mafioso, the politician, the policeman or the corrupt businessman who has put a price on our heads. Yet we yearn for the privacy and anonymity that would allow us to move around without being recognised, for those times when we used to have no need to conceal the names of our family members (for they are now vulnerable too).

We are the enemy, and truth is the enemy of a nation refusing to engage in self-criticism and assume responsibility for its own tragedy. Sixty-four journalists have died in my country. Not one of these murders has been explained.

In Mexico, death threats are hardly newsworthy. Nor is death, or the struggle to remain alive. Maybe this is why my father, in solidarity and with great emotion, asks me why I refuse to accept the idea of living in another country for a while, one where I would not be considered an enemy of the state because I defend human dignity.

Six years ago, when I was imprisoned and tortured by a mafia who trafficked in minors and in child pornography, parts of the Mexican media exclaimed: “A woman who opposes mafia power”, as if in surprise. Thanks to their reaction, society looked at and listened to me, but most importantly of all, it reacted and demanded justice for the hundreds of children who are the victims of sexual tourism and child pornography. Legislators created new laws to protect children, and when I was cleared of defamation charges, women on the streets, old and young, applauded and embraced me. They stopped me in public places to congratulate me on having reminded them that truth has power – and so do women who refuse to subject themselves to macho violence.

Only the other day, as I was pushing my trolley along the supermarket aisle, two older women approached me and asked, “Are you the writer?” Timidly, I said, “Yes”. One woman threw herself at me for a typically Mexican-style embrace, informing me that her granddaughter wrote an essay at primary school on her chosen heroine. It was me. “Why did she choose me?” I asked, and she answered: “Because we are all a little bit like you, and you remind us of it, when you refuse to give in, when you won’t hold your tongue, and when you smile and tell us that the world is also ours.”

Perhaps that’s what it comes down to in the end. Journalism brings it all together. We can’t ask others for something we are not inclined to give. There are moments to listen and others to be listened to. It is not enough to arouse empathy; it is not our job to make people cry. What we have to do is to reflect an outrageous reality with such power that it inspires the hope that all people want to participate in and be responsible for change. Objective journalism does not exist: we are not objects. We are subjects, so we write subjective journalism, and to do that well, everyone’s rights and everyone’s lives are of equal importance. Sometimes we tell the story. And at other times, we are the story.

Lydia Cacho’s most recent book is Slaves of Power: A Journey into Sex Trafficking around the World (Debate). She was awarded the PEN/Pinter Prize for an international writer of courage in October 2010

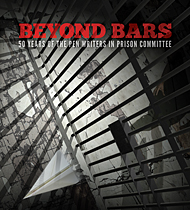

This is an edited version of an article which appears in Index on Censorship’s latest issue, Beyond Bars: 50 Years of PEN’s Writers in Prison Committee.

This is an edited version of an article which appears in Index on Censorship’s latest issue, Beyond Bars: 50 Years of PEN’s Writers in Prison Committee.

If you want to read more from Lydia Cacho, subscribe to Index on Censorship via Exact Editions. You will gain access to Index’s archive including Volume 38, Number 3 featuring Terror on the Highway in which Cacho tells the remarkable story of how she survived an abduction