Obscenity laws, religion and self-censorship continue to blight India’s cultural scene. Leo Mirani reports

Obscenity laws, religion and self-censorship continue to blight India’s cultural scene. Leo Mirani reports

While much of the Indian media’s attention over the last few weeks has been devoted to the Jaipur Literature Festival and the spat between journalist Hartosh Singh Bal and author William Dalrymple, the less trivial (and less glamorous) events at the India Art Summit went largely unnoticed.

The India Art Summit has been called “the world’s biggest fair of modern and contemporary Indian art”. With 84 galleries exhibiting the work of about 500 artists, it has grown in both size and stature since its inception in 2008 and aspires to be counted among the world’s great art fairs. This, however, is a dream that is unlikely to be realised as long as Indian arts and culture remain bound within the limits drawn by extra-legal censorship.

For the third event running (there was no summit in 2010), the organisers had to take down the works of India’s best-known artist, MF Husain, after threats of violence and vandalism. Delhi Art Gallery’s Ashish Anand, who exhibited the paintings, said he received more than two dozen threatening emails, some containing abusive language. “Could you please stop exhibiting this bastard’s paintings? I am very disappointed being an Indian and definitely look for revenge in case of any such artworks being allowed to exhibit,” read one email. Considering the past record of various Hindu right-wing groups — which includes vandalising a research institute in Pune, disrupting screenings of a film about homosexuality and attacking newspaper offices — it was inevitable that the organisers would remove the offending paintings.

For the third event running (there was no summit in 2010), the organisers had to take down the works of India’s best-known artist, MF Husain, after threats of violence and vandalism. Delhi Art Gallery’s Ashish Anand, who exhibited the paintings, said he received more than two dozen threatening emails, some containing abusive language. “Could you please stop exhibiting this bastard’s paintings? I am very disappointed being an Indian and definitely look for revenge in case of any such artworks being allowed to exhibit,” read one email. Considering the past record of various Hindu right-wing groups — which includes vandalising a research institute in Pune, disrupting screenings of a film about homosexuality and attacking newspaper offices — it was inevitable that the organisers would remove the offending paintings.

The following day, the organisers of the summit remounted Husain’s work citing assurances from the police and Ministry of Culture that there would be adequate security. This was seen as a victory against Hindu extremists.

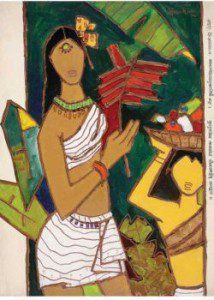

There are two troubling aspects to this story. First, the exact same thing happened at the inaugural summit in 2008 and again in 2009. Considering the dull consistency with which the Hindu right seeks to throw its weight around and gain publicity though intimidation, surely the organisers and the police should have been better prepared for such threats from the very beginning. Husain, who is considered India’s finest living artist, has been the subject of harassment for a number of years, and by his own reckoning has some 3000 cases registered against him. The Hindu right objected to Husain, a Muslim, painting Hindu goddesses in the nude, saying it offends them. Shows exhibiting his work have been routinely attacked. Such was the persecution the 95-year-old artist faced, he eventually surrendered his Indian passport and accepted Qatari citizenship.

Secondly, the organisers’ wishy-washy behaviour shows not only an (understandable) lack of faith in the security services but also in the organisers’ own beliefs. Their easy acquiescence to vigilante thugs intent on “protecting the culture” and “policing the morals” of Indians is a sign of how deeply ingrained this climate of fear and intimidation has become. Remounting the painting after agreeing to take them down dilutes any impact that continuing to exhibit the works might have had.

The intimidation of artists, writers, intellectuals and journalists by right-wing extremists is now an accepted fact of day-to-day life. Earlier this year, young Aditya Thackeray, the 20-year-old leader of the Yuva Sena, the youth wing of the right wing nativist party Shiv Sena, demanded that Mumbai University remove Rohinton Mistry’s 1991 novel Such a Long Journey from its syllabus because, he claimed, it offended Maharashtrians. The University’s vice-chancellor fell over himself to comply. When the Shiv Sena demanded that producer Karan Johan change the name of a fictional magazine, Bombay Beat, to Mumbai Beat, in his equally fictional film, Wake Up Sid, the producer rushed to grovel in apology. It bears repeating that India was the first country to ban Salman Rushdie’s Satanic Verses.

While it is deplorable, it is also hard to blame filmmakers and writers for their wimpishness. Freedom of speech must be upheld by the state and those who engage in violent censorship must have action taken against them. Yet, the police are not only disinterested and ineffectual but sometimes also involved. A 2006 art exhibition in Mumbai called “Tits, Clits ‘n’ Elephant Dick” drew one solitary protest from a woman who considered it obscene. The Mumbai police promptly arrested the artists for breaching obscenity laws.

It is a sign of how inured this supposedly liberal democracy has become to censorship and how accepted it is in India’s culture that when a journalist writes that a Briton is lording it over the Indian literary scene, it sparks furious debate in Indian papers and blogs. But when yet another wedge is cut out of our rapidly eroding civil liberties, it is readily accepted and forgotten in the turn of a page.

Leo Mirani is the editor of the Time Out guide to Mumbai and Goa