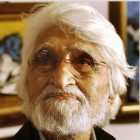

For almost 20 years, artist MF Husain was threatened and his work abused. Salil Tripathi says goodbye to a controversial and spell-binding master

For almost 20 years, artist MF Husain was threatened and his work abused. Salil Tripathi says goodbye to a controversial and spell-binding master

Maqbul Fida Husain, who died in London today, was an involuntary exile. He loved London, but his heart belonged to India. Many Indians, including the government, celebrated him, but vigilantes in India did not like some of his paintings, and succeeded in hounding him out of India. He was a worthy recipient of an Index on Censorship award earlier this year; he could not attend the event itself. He divided his time between the Middle East during the winter and London during summer, unable to return to India because he would not have been allowed to paint there in peace.

In the mid-1990s, a magazine in India found an old sketch of a nude Saraswati, the Hindu goddess of learning, which Husain had painted. The sketch is elegant and clean; and while it does not “resemble” Saraswati (for who knows what she really looked like?), it was his interpretation of Saraswati. But many Hindus felt offended because she was painted without any clothes. Then, they searched through his paintings and found many other paintings which also showed Hindu divinities without clothes. None of that was gratuitous, nor was it surprising: Hindus have painted their gods and goddesses without clothes for more than a thousand years. There is a concept, of nirakara, or formless, which lies at the heart of this: that you imagine what your deity might look like, giving the formless some shape.

That was too profound for the fundamentalists, and they began campaigning against him, in India and abroad. In 2006, the Asia House in central London had to cancel an exhibition of his works after unknown assailants damaged paintings. An art gallery showing his work in India was attacked. A television studio was attacked after a programme it produced asked viewers whether whether Husain should be given India’s highest civilian honour, the Bharat Ratna.

At one time, hundreds of cases were filed against him. India has peculiar laws dating from colonial times, introduced by Britain soon after the rebellion of 1857 to keep communities separate and segregated. India kept them on the books, allowing bullies to terrorise artists and writers: the laws allow anyone who feels offended to lodge a complaint, which is then initiated by the state. Husain was prosecuted under Section 295 of the Indian Penal Code, which outlaws insulting religions, and section 153A, which deals with promoting enmity between groups.

Courts, which are supposed to judge if such cases have merit, would often accept the cases nonetheless, and had Husain lived in India and wanted to be a law-abiding citizen, he’d have spent the better part of his life criss-crossing across the vast country, appearing in different courts. There was no guarantee that fresh charges would not be brought against him — his presence in a town could be considered likely to cause violence, and so new, criminal charges could easily be imposed on him, with no certainty that he’d get bail.

In the end, higher courts threw out the cases, and, in a more polite tone, told his critics to get a life. But in India, that does not end the matter. And the kind of people who had ransacked galleries or attacked the TV studios made violent threats against him.

Against his wishes, and in a decision that must have broken his heart, Husain left India. In 2010, he accepted Qatari citizenship. Since 1995, when the troubles started, Husain saw his canvases defaced in India, his family harassed, his property attached, his personality ridiculed, his art physically attacked and his work deliberately and disingenuously misinterpreted. His art has captured India’s ethos. He was India’s chronicler, portraying the stark agony of a cyclone; a court jester, painting Indira Gandhi as Durga astride a tiger after she declared Emergency; a cheerleader, celebrating the centuries of Sunil Gavaskar; an inventive exhibitionist, painting as Bhimsen Joshi sang, painting with Shah Rukh Khan, painting on the body of a woman.

When he left India, some nationalists claimed betrayal. The more important question is: did Husain betray India, or did India betray its own ethos? My book, Offence: The Hindu Case, began with a long anecdote about Husain’s absence from the opening of the National Gallery of Modern Art in Bombay’s exhibition of the Progressive Artists’ Group, which came into being soon after Independence. Husain could not attend because of threats against him. Towards the end of my book, I had hoped for a happy ending.

Salil Tripathi, a writer in London, is chair of English PEN’s Writers-in-Prison Committee. He first met Husain in 1982, and instead of writing an interview, he wrote a poem about him. His book, Offence: The Hindu Case, can be ordered here.