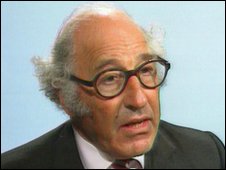

As British journalism faces the most significant public inquiry in a generation, Julian Petley talks to former Press Council chief Louis Blom-Cooper about ethics, public debate and maintaining a free press

The Leveson inquiry, whose remit includes examining “the culture, practices, and ethics of the press”, as well as making recommendations for a “new more effective policy and regulatory regime which supports the integrity and freedom of the press:, represents a twice-in-a-lifetime opportunity to reform the behaviour of the press and the manner in which it is regulated. Why twice? Because we’ve actually been here before.

During the 80s, intrusive and generally excessive behaviour by the popular press led to a growing number of calls in Parliament for newspapers to be regulated more effectively. In 1981, Frank Allaun introduced what was to be the first of a series of private members’ Bills calling for a statutory right of reply for members of the public against whom allegations had been made in the media as a whole; Austin Mitchell introduced a similar Bill in 1984, and in 1987 Ann Clywd brought forward her Unfair Reporting and Right of Reply Bill. These were all Labour MPs, but in 1987 the Tory MP William Cash presented his Right of Privacy Bill, and the following year another Tory, John Browne, introduced a Protection of Privacy Bill, closely followed by Labour MP Tony Worthington’s Right of Reply Bill.

In 1980, the Campaign for Press and Broadcasting Freedom set up an independent inquiry into the Press Council, chaired by Geoffrey Robertson QC. This produced the highly critical report People Against the Press, which called for the Council to be given considerably sharper teeth and for the creation of a statutory press ombudsman, as well as for a Freedom of Information Act and the relaxation of laws which hindered investigative reporting. (In the present context, this is a work which urgently needs revisiting.) In February 1987, Lord Longford initiated a debate on press standards in the Lords, and in July of the same year Labour forced a debate in the Commons on Murdoch’s acquisition of the Today newspaper.

By the late 1980s, loud demands for press reform were therefore very firmly on the political and social agenda. This led to the appointment in 1988 of the eminent QC Sir Louis Blom-Cooper as the new head of the Press Council, with the aim of making it a more respected, authoritative and effective self-regulatory body. Like Geoffrey Robertson, Blom-Cooper was concerned both to protect, and indeed to enlarge, the freedom to practise serious journalism which was clearly in the public interest, but also to provide forms of redress for those who had been the victims of mere muckraking and scandalmongering.

The problem was, however, that the popular press cared little for the former kind of journalism but was determined to protect the latter at all costs. Thus Blom-Cooper’s reforms not only found little support amongst owners and editors (and by no means only at the popular end of the market), but he himself became the target of press mischief-making, both in the newspapers themselves and, more damagingly still, behind the scenes in Westminster and Whitehall. Thus the Council was described in the news- papers it was supposed to be regulating as consisting of “pompous laymen and self-important journalists”, as straying “too far into the jungles of taste and discretion”, as a “bunch of loonies” (the Sun, inevitably) and as issuing “hectoring encyclicals”.

Seemingly showing little faith in Blom-Cooper’s reforms, in 1989 the government responded to the growing clamour over press misbehaviour by establishing a committee of inquiry under Sir David Calcutt QC, whose remit was to “consider what measures (whether legislative or otherwise) are needed to give further protection to individual privacy from the activities of the press and improve recourse against the press for the individual citizen”. The writing was clearly on the wall for the Council, and indeed Calcutt was to recommend its abolition and its replacement by the Press Complaints Commission, a body with, to the delight of the press, an even narrower remit than its predecessor, being an organisation which was concerned solely with receiving, mediating and adjudicating on complaints.

The press attitude to Louis Blom-Cooper’s reforms demonstrated all too clearly that the newspaper owners and editors simply would not countenance any self-regulatory measure of which they themselves did not approve. Furthermore, they used their considerable political influence to help into existence a neutered body with which they would feel considerably more at ease. And as absolutely nothing has changed, at least for the better, since the death of the Press Council and the birth of the PCC, this immediately raises a crucial question: even if Leveson does come up with proposals for effective press reform, would the government be prepared to enact them in the teeth of massive, daily press hostility? Past experience suggests that it would not. Even now the knives are out for Leveson in papers such as the Daily Mail, and it’s likely that the government is being relentlessly lobbied by the press barons behind Leveson’s back. Indeed, given that one of the other matters which Leveson is investigating is ‘the relationship between national newspapers and politicians’, he already has a ready-made case study right under his nose.

Julian Petley: What opportunities for press reform do you think are presented by the Leveson Inquiry?

Louis Blom-Cooper: In my view, Leveson presents us with a golden opportunity to do something on the grand scale. All the focus on the press has been, for historical reasons, on complaints, but handling complaints is a disciplinary function, it’s not about monitoring or supervising. What the public needs is to know what its press is doing on its behalf, and also what it is not doing — for example, the reporting of the activities of government prior to the war in Iraq, about which we were left almost totally in the dark because newspapers were not reporting them.

Julian Petley: There has been a great deal of discussion about whether any new arrangements should be independent, self-regulatory or statutory. What’s your view?

Louis Blom-Cooper: I go absolutely spare when people say that whatever intervention there is it must be non-statutory. This is a total nonsense. It depends entirely on what the statute seeks to achieve and what it contains. I also think we need to get rid of the word “regulation”; what we actually need is an independent body which carries out monitoring — independent monitoring of the press. The word “regulation” implies, I think, to some people, some form of executive power, and what I would propose does not contain executive power.

Any form of public intervention to create such a body would require legislation in the first instance. But one absolutely does not want the supervision to be carried out by government itself, rather the government should establish an independent, standing body by means of statute, namely a Commission. The statute establishing the Commission would also set up an Appointments Commission which would consist of, for example, the chairmen of the British Library, the British Museum, the Association of Vice-Chancellors and Principals of Universities, the Lord Chief Justice of England, the Lord President of the Court of Sessions; they wouldn’t be specifically named people, but the people who held these offices at the time of selection. One would thus put between the institution of government and the public itself a wholly independent body, independently selected.

Julian Petley: What powers would this body have?

Louis Blom-Cooper: This brings us back to the nature of the body itself. I would have a standing Royal Commission composed of people who were entirely independent of publishing in any form and appointed in the fashion which I’ve just mentioned. And it should certainly include members of the public; half of the people appointed to the Press Council were members of the public, and every year we used to receive more than 1,000 applications. This certainly wasn’t replicated in the PCC. As I’ve said, this body should be conceived on the grand scale. For example, it should be involved in the question of the education and training of journalists, and in ensuring that there is plurality of press ownership, so that in the case of mergers they can examine whether or not they should take place. In all of these matters it should be undertaking investigations, not exercising executive power. What I do think vitally important would be the Commission’s ability to conduct public inquiries, and the statute would have to give it all the necessary procedural powers to conduct such inquiries, in particular the power to subpoena witnesses. These are what the Press Council sadly, and damagingly, lacked when it carried out its inquiries into press behaviour in the Peter Sutcliffe case and the 1990 Strangeways Prison riot. These would be statutory powers, but they would be procedural, they wouldn’t deal with the substance.

Julian Petley: How would the Commission be funded?

Louis Blom-Cooper: The Commission would have to be funded by Parliament, to whom it would be answerable, and they would have to go to Parliament every year with their budget, just as the Supreme Court has to do, to ask for money to support their activities. So it would have to be funded out of the public purse and not, for example, by a levy on the newspapers: one doesn’t want the press to have any interest, as it were, in the activities of this body. My parallel here, structurally and constitutionally, would be the Standing Royal Commission on the Environment, which is constantly looking at what’s happening to the environment, or PhonepayPlus [formerly known as ICSTIS], the regulatory body for all premium rate phone-paid services in the United Kingdom.

Julian Petley: Would the Commission deal with complaints against individual newspapers?

Louis Blom-Cooper: No doubt one of the Commission’s functions might involve receiving and adjudicating on complaints, but I don’t think that complaints are what really matters here. And, incidentally, insofar as complaints do matter, in my view the first clause of the PCC Code, which has to do with accuracy, is far more important than the one pertaining to privacy. The real problem is the daily lying, cheating and distorting in the press, all of which fall under the first clause of the Code.

Julian Petley: Indeed. Let’s just remind ourselves of what this actually says: (i) The press must take care not to publish inaccurate, misleading or distorted information, including pictures. (ii) A significant inaccuracy, misleading statement or distortion once recognised must be corrected, promptly and with due prominence, and — where appropriate — an apology published. In cases involving the Commission, prominence should be agreed with the PCC in advance. (iii) The press, whilst free to be partisan, must distinguish clearly between comment, conjecture and fact. Now, this is trampled on daily and routinely treated with absolute contempt, particularly by the popular press. You have only to open any popular paper with the code beside you to realise the yawning chasm between the rule and the reality. Thus it’s entirely unsurprising that the PCC’s own statistics reveal that, in 2009, 87.2 per cent of the complaints which it received concerned accuracy and opportunity to reply, and only 23.7 per cent were about privacy.

Louis Blom-Cooper: Indeed, but I’m not sure that I’d necessarily get rid of the PCC under the arrangements which I’ve just outlined — if the industry itself wishes to deal with complaints against its members, why the hell shouldn’t it? It seems to me a perfectly sensible exercise on the part of any employer to want to know what is in fact happening amongst his own employees. On the other hand, it does need to be stressed that self-regulation in the newspaper industry has proved to be self-serving; it aims to protect the newspaper industry from anything that would impose responsible conduct on proprietors, editors and journalists by an independent agency. It has palpably not served the public interest. And the PCC Code is constructed entirely within the newspaper industry for the benefit of its practitioners, rather than as a standard bearer of ethical behaviour for the public.

But the really important point about the body which I’m advocating is that the statutory power which it would have would be non-executive, that is to say that it would have no direct control over journalists or editors — it would act by precept. Its main function would be monitoring — looking at the press day in and day out and telling the public what it is and, equally importantly, isn’t, doing. It could organise conferences with practitioners in journalism. It would keep under review all the laws affecting the press. It would make representation to the Competition Commission in cases involving takeovers. It should promote centres for the advanced study of and research in journalism. In all these things the Commission would aim to assist the newspaper industry in defining a set of workable standards, and to act as a forum for public debate on the freedom of the press.

It really is extremely important to understand, as I said in my 2007 lecture in honour of Professor Harry Street [“regulation of the media is entirely compatible with, indeed required by, society’s commitment to the values of freedom of speech. There is a need for a new watchdog which barks authoritatively, and, where appropriate, in stentorian terms, but does not bite, except indirectly and influentially”].

Julian Petley: I would agree entirely, but unfortunately the press has done its absolute utmost to equate regulation with censorship.

Louis Blom-Cooper: Yes it has, but what I’m talking about has nothing to do with controlling the press, because I regard all press freedom as simply a manifestation of our individual freedom; that is to say, we give to the press the duty to practise collectively and on our behalf the freedom of expression which we all possess under Article 10 of the European Convention on Human Rights. Freedom of speech belongs to all of us, it belongs equally to those who work in the media and to those who don’t. It’s particularly important to understand that such a conception of freedom of expression rules out the licensing of journalists. As Harry Street himself argued in Freedom, the Individual and the Law, journalism is “the exercise by occupation of the right to free expression available to every citizen. That right, being available to all, cannot in principle be withdrawn from a few by any system of licens- ing or professional registration”. No one can be prevented from exercising free speech other than by a law which applies to everybody. But, of course, there’s nothing necessarily wrong in restricting and confining freedom of expression by rules of law which do apply to everyone. If freedom of the press means no more than our collective rights performed on our behalf by those daily engaged in newsgathering, then we (the public), in the form of democratic government, should determine how far we should restrict our collective rights, and how the press is to be monitored and supervised. And it is certainly the case that current concerns about the standards of journalism suffice to demand both public debate and governmental action.

Julian Petley: Again, I would agree, but unfortunately the way in which press owners and their appointed editors understand press freedom in this country has precious little to do with Article 10. What they appear to mean by press freedom is the freedom to do just what the hell they like with the newspapers which they own and run. What we have here is in fact simply a smokescreen, the assertion of a property right in the guise of a free speech right, and an extremely arrogant claim that newspapers should be immune from regula- tions which apply to everyone else.

Louis Blom-Cooper: But such a position is wholly untenable. Tell me where, constitutionally, do they get that idea from? Maybe things have developed in this fashion, but tell me what is the legal basis for the present state of affairs? The only legal basis for freedom of the press is Article 10.

Julian Petley: Of course, but the kind of people to whom I’m referring don’t give a damn about Article 10 — all they’re concerned with is the threat posed by Article 8 to their commercial lifeblood of kiss ’n’ tell stories. Indeed, they want the government to rip up the Human Rights Act (HRA) and to withdraw from the European Convention on Human Rights, and their papers are filled day in and day out with the most poisonous and ill-informed stories peddling this particular line. The fact that British newspapers clearly hate the whole notion of human rights tells you everything you need to know about the fundamentally populist, illiberal and indeed anti-democratic nature of much of the British press.

Louis Blom-Cooper: Maybe, but the press’ argument is hopeless, because they’re caught by the Human Rights Act whether they like it or not. And the whole campaign against both the Act and the Convention is just historically illiterate and utter nonsense. One of the things which I found most disappointing about Ed Miliband’s speech at this year’s Labour conference was that there was absolutely no acknowledgement of probably the best thing that Labour did when it was in office, namely to introduce the Human Rights Act. There’s Nick Clegg nailing his flag to the mast of the HRA, and delightfully so, but how much better it would have been if Miliband had said that “we are the architects of the HRA and we have no intention ever of seeing it destroyed”.

Julian Petley: Which they’ll never say, because they wake up every morning terrified of what has been written about them in the right-wing press. What Leveson really needs to investigate is how we’ve arrived at a situation in which, thanks to politicians’ pusillanimity in the face of newspaper bullying, the likes of Paul Dacre, who is accountable only to his readers, effectively dictate government policy on a wide range of social issues. However, turning back to Leveson, do you think that the Calcutt Inquiry, the death of the Press Council and the subsequent creation of the Press Complaints Commission hold any lessons for the present moment?

Julian Petley: Which they’ll never say, because they wake up every morning terrified of what has been written about them in the right-wing press. What Leveson really needs to investigate is how we’ve arrived at a situation in which, thanks to politicians’ pusillanimity in the face of newspaper bullying, the likes of Paul Dacre, who is accountable only to his readers, effectively dictate government policy on a wide range of social issues. However, turning back to Leveson, do you think that the Calcutt Inquiry, the death of the Press Council and the subsequent creation of the Press Complaints Commission hold any lessons for the present moment?

Louis Blom-Cooper: The Calcutt Committee came to the conclusion that a body like the Press Council which, under my chairmanship, was pro- moting the freedom of the press was incompatible with a complaints body. And that was the reason for getting rid of it — the newspaper industry did not like the way that I was wanting to take the Council, to make it a public body which, whilst dealing with complaints, was very much there for the public. In other words, its primary function was not to protect the industry but to give the public something which they could recognise and accept with confidence as being on their side. So it was in the industry’s interest that the PCC was established, and from my very first day at the Council prominent people in the newspaper industry set about getting rid of me. And when Calcutt was set up, the industry saw this as the perfect opportunity to further their interests in the abolition of the Press Council.

This article appears in Dark Matter the new edition of Index on Censorship magazine, which explores science and censorship.

Click here for subscription options and more

Follow Index’s coverage of the Leveson Inquiry here and on Twitter @IndexLeveson