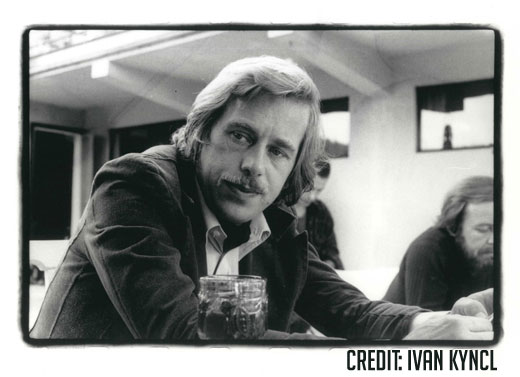

How are ordinary, decent people to react to the imposition of a repressive regime, how much should they risk in showing their opposition to it? These questions were raised by Ludvik Vaculik in a feuilleton he wrote in December 1978, which brought an indignant reply from Václav Havel, as well as a dozen other dissidents. The controversy was given a poignant twist by the arrest of Václav Havel, together with nine other Chartists. Prior to his arrest, he had been under virtual house arrest for several months.

Václav Havel died on 17 December this year.

On bravery

I sometimes wonder if I’m mature enough to go to prison. It frightens me. We should all come to terms with this problem once we reach adulthood, and either behave in such a way as not to have to fear imprisonment or consider what is worth such a risk. It is hard to be locked up for something that will have ceased to excite anyone even before your sentence is up. That, I think, is what happened to the people who were imprisoned for the pre-election leaflets in 1972. And that is why I was greatly moved and encouraged by Jifi Miiller’s message from prison in which he advised people to act in an effective way and to avoid arrest.

It is one thing if they imprison someone who knows exactly what he is doing and why, and quite another when a young, immature person lands in jail, more or less by accident. I was amazed, for instance, by the fate of Karel Pecka (a leading dissident writer who made his literary debut in the sixties), who frittered his youth away in the uranium mines. For someone to be able to pick up the pieces of such a wrecked life and to give it a meaning and value I believe requires a kind of courage he surely did not possess before his prison experience. A normal human being, even a relatively calm one, if he opens a chess game badly, feels like sweeping the board clean and starting again. You can do that in a game of chess, but you can’t do it in life.

Just to risk imprisonment is not in itself any kind of achievement, nor is it at all a good thing if during a dispute one side provokes the other to take a step which cannot be revoked without loss of honour, prestige, or authority. To do that can only make the situation worse. A man who suppresses the opinions of others is merely a censor; a censor, whom resistance to censorship leads to imprison people, becomes a dictator; the dictator who, in suppressing a protest demonstration, gives orders to fire at the crowd is a murderer. With the censor we could negotiate, and there was always a possibility that, as a result, his office would in time be abolished, and the censor himself would quietly accept some other desk job. In a murderer we have an enemy who cannot agree to any negotiation if he is not to end on the gallows.

However, where are the decent limits to such reflections?

No one can give a satisfactory reply to the question whether Charter 77 has made things better or worse, and how things would look today without it. Let us give up seeking such an answer, and let us add that the moral motives for our actions are only roughly parallel with political ones, the strongest impulses deriving from our character rather than our views. Charter 77 is today different from what it was in 1977. We have all had our share of trouble. I sometimes hear complaints that it is no longer as nice as it used to be. To this I would say that anyone who doesn’t agree with what those who remain active and committed are doing, should withdraw quietly and undemonstratively and not hamper the work of those who are left. Each and every one of us can try and find methods which suit him best. If some team of people under threat decides to re-define its internal structure and tighten its rules, it can hardly expect to be understood by the public at large. While, on the one hand, a free man is put off by demands for absolute unity, on the other, the majority of sensible people tend to regard the increasingly more heroic actions of an increasingly diminishing platoon of fighters as more and more their own personal affair. I mean this generally, as it applies to all shades of opinion.

Most people are well aware of their own limits and refrain from actions whose consequences they would be unable to bear. Anyone who, in a cool season, persuades people to take on more, should not be surprised when they break. An instinctive fear of hunger prevents a healthy and sensible person from feeling sympathy for someone who, in his own and the general cause, goes on hunger-strike. A matter of life and death? The sensible person gets cold feet and tries to find a way of dissociating himself from it at least a little. Psychologists and politicians cannot expect heroism in everyday life except when the whole environment is literally ionised by radiation from some powerful source. Heroic deeds are alien to everyday life. They are special events, which ought to be reported. They flourish in exceptional situations, but these must not be of long duration. A mass psychosis of heroism is a fine thing, provided there are in the vicinity some sober minds who have access to information and contacts and who know what’s to be done afterwards.

I make a distinction between heroism and the integrity of the ordinary man. The ordinary man has a reserve of good habits and virtues, possesses his own integrity and knows how to protect it from erosion. Just as he doesn’t like to see anyone acting in too dangerously defiant a manner, he also likes to reassure himself that quiet, honest toil is the best, even if it isn’t particularly well rewarded, and that decent behaviour will find a decent response. Today, the main brunt of the attack is not directed so much at heroes as against what we used to consider the norm of work, behaviour and relationships. I would go so far as to say that the heroes are being given only measured doses of repression, which the regime feels duty bound to administer. It is reluctant to do this because it doesn’t want to give publicity to any heroes. The war should remain anonymous, without any recognisable faces or data. That is why the real explosive charges are scattered among the crowd, the intention being not to destroy anyone but rather to cause him to change his norms. A kind of neutron bomb: undamaged empty figures carry on walking to and from work.

We sometimes argue whether things are worse now than in the fifties, or if they are better. We can find sufficient evidence for both contentions. A truthful assessment will depend on how much we can gain from our present situation to benefit the future. The fifties had their revolutionary cruelty as well as their selfless enthusiasm. Certain sections of the population suffered grievously. Today there is no sign of any enthusiasm and, except: in the case of a few excesses, no particular cruelty. Also, it no longer matters to which group anyone belongs. Violence has become humanised. The total surveillance of the entire population has been spread more gently over everyone and everything, it is devoid of the former spasms of hate. Is this better or worse? It is an attack on the very concept of normal life. I consider it more dangerous than in the fifties, yet we find it easier to live with.

Under these circumstances, every bit of honest work, every expression of incorruptibility, every gesture of goodwill, every deviation from cold routine, and every step or glance without a mask has the value of a heroic deed. Our opponent, in particular, should find us ready – not to die for some rotten sacred cause, but to understand its positive aspects and to hold on to them. While heroic deeds frighten people, giving them the truthful excuse that they are not made for them, everyone can bravely adhere to the norm of good bshaviour at the price of acceptable sacrifice, and everyone knows it. Prague, 6 December 1978 – on the occasion of Karel Pecka’s 50th birthday.

Dear Mr. Ludvik

You say: either one should act so as not to have to fear prison, or else consider whether it’s worth his while to risk imprisonment.

I agree: if one intends to burgle a supermarket, one has to consider whether the likely proceeds make the risk worthwhile.

But people aren’t locked up only for burgling supermarkets. They are locked up, for instance, for writing novels. A certain Vaculik was not locked up for his Guinea-pigs, but a certain Grusa was locked up for his Questionnaire.

According to you, Grusa evidently acted carelessly in writing The Questionnaire, since it is stupid to go to prison. Vaculik was more prudent in writing only The Guinea-pigs. You see, I trust, how absurd this is. After all, you know better than anyone that Grusa didn’t have to go inside for The Questionnaire but Vaculik might have gone inside for The Guinea-pigs. You know that the decision

whether to lock up Grusa or Vaculik has nothing at all to do with which one of them was better able to assess the risks, it is purely and simply a cold-blooded calculation on the part of the powersthat-be. Sometimes it is more tactical to arrest Grusa and thus try and intimidate Vaculik, at other times it might be better to arrest Vaculik and thus try and intimidate Grusa.

Grusa’s novel is a good one, and so to that extent the two months inside were worth it. But what if it had not been a good novel? Or what if he had spent two years behind bars instead of two months? Then no doubt it would be incumbent on us to pity Grusa, as we pitied those naive souls who, in the early seventies, thought they could get away with reminding voters of their constitutional right not to vote.

But don’t you remember that you and me both still have the 1969 indictment hanging over us? And surely you cannot be unaware that it could easily have been the two of us who spent all those years in jail instead of Sabata and Hiibl? Do you think that the text we both signed was worth it?

In a sense, nothing is worth it. Not leaflets, nor attendance at a ball, nor the writing of a novel. And what about sending the manuscripts of Czech authors to emigre magazines! Was it worth it where Lederer was concerned? Good job he is one of those cunning heroes who benefit from ‘measured doses of repression’ – after all, he might have got not three years but ten. The law under which they sentenced him allows for that.

Was it worth it for Messrs Simsa and Sabata that they behaved like men when humiliated? Of course not; all they had to do was to bend and people would at once have understood them better and they need not have found themselves among those repugnant heroes. And what about the Plastic

People – had they given concerts with Helena Vondrackova they would have taken their place among decent people within the limits of the law and needn’t have come a cropper.

I don’t know what you had in mind when you wrote your feuilleton. All I know is what effect it has. Divested of its stylistic elegance, it can be summed up like this: a decent bloke doesn’t pretend to be a hero and doesn’t insist on getting himself arrested. Because to be a hero is somehow anti-social; this isn’t the honest, everyday work which decent people respect and which keeps society going; people recoil from it and are frightened by it. Furthermore, heroes are dangerous because they only serve to make matters worse. After all, the secret police aren’t such bad chaps provided they are treated decently.

Why then provoke them needlessly by writing novels, making music, sending books abroad? This literally forces those decent chaps to beat up women and drag one’s friends into the woods and there kick them in the balls. We must have more regard for their prestige and stop invoking all these international treaties, we must no longer insolently copy the writings of people like Cerny, Vaculik, Havel, and others like them – no doubt you know that for this reason three boys of the same age as your sons are at present in a Brno jail. More heroes, who are only helping to make matters worse.

But now without exaggeration: none of us can know in advance how much we can bear, nor what we may be made to bear. That can only be known by your calculating model of a sensible, decent man within the limits of the law. None of us decided in advance that we wanted to go to jail, indeed none of us made a conscious decision that he or she wanted to become a dissident. We became dissidents without actually knowing how, and we found ourselves behind bars without really knowing how. We simply did certain things which we had to do and which it seemed proper to do: nothing more, nor less.

Happy are those who are decent and haven’t landed in jail. But why should those who had that misfortune be set apart from the others? Is it not usually quite arbitrary who lands in it and who doesn’t? Those whom you call heroes, suggesting that they are overdoing things, didn’t get locked up for their ambition to become martyrs – they were locked up because of the indecency of those who put people in jail for writing novels or for playing tapes with the music of unofficial musicians.

No one wants to go to jail. If people were to take your advice and calculate the risks involved in the fashion of a thief deciding whether to burgle a supermarket, there would for a long time now have been in our country not a single expression of solidarity with an unjustly persecuted person, not a single truthful novel or free song, not even a single feuilleton. For how can we be sure that tomorrow they won’t start putting people away for writing feuilletons?

Maybe all you meant to say was that the quiet and inconspicuous humiliation of thousands of anonymous people was worse than the occasional arrest of a well-known dissident. Undoubtedly. But the question surely is, why did they arrest the dissident? Mainly, if you think about it, just because he had tried to tell the truth about that quiet and inconspicuous humiliation of thousands of anonymous people.

Some of us have been experiencing this harsh and depressing confrontation with the secret police for two years, others for ten, still others all their life. Nobody can be said to enjoy it. None of us knows in advance how long he can stand it. And each and every one of us has the right, when he feels he can’t stand it any longer, to draw back, not to do certain things any more, to take; a rest, or even to emigrate. All this is understandable, normal, human – and I’d be the last to hold it against anyone.

What I do hold against people, though, is when they don’t tell the truth. And you – forgive me – this time are not telling the truth.

Yours

Václav Havel

This article originally appeared in Index on Censorship magazine in 1979 Issue 8: Volume 39