Index relies entirely on the support of donors and readers to do its work.

Help us keep amplifying censored voices today.

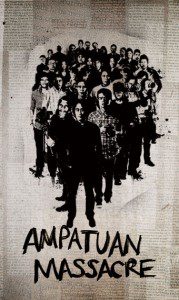

MURDERED 23 NOVEMBER 2009

MURDERED 23 NOVEMBER 2009

Ampatuan massacre victims, Ampatuan — Maguindanao, Philippines

Join us in demanding action for the victims of the Ampatuan massacre. On 23 November 2009, Esmael Mangudadatu planned to register his candidacy for governor of Maguindanao. His rivals from the Ampatuan clan – who have controlled Maguindanao since 2001 with the backing of the Philippine government – had vowed to block his efforts, so instead he sent along journalists and some female relatives, believing they would be safe. An hour into the drive, 200 armed men ambushed the convoy; 58 people, including 32 journalists and media workers, were slaughtered in the single deadliest incident for journalists in history.

Two years on, dozens of suspects remain at large, including members of the Ampatuan family. The trials have been painfully slow, and attempts to subvert the judicial process – with bribes, threats and intimidation of families and witnesses – continue. The Ampatuans have been linked to at least 56 other killings over the past 20 years. The government has failed to seriously investigate any of the atrocities.

Click here for a full list of those killed.

International Day to End Impunity is on 23 November. Until that date, we will reveal a story each day of a journalist, writer or free expression advocate who was killed in the line of duty.

This article was first published in the Guardian

Nothing titillates journalists more than talking about their profession or, should I call it, their trade. The Leveson inquiry has spawned almost daily public discussions about the future of the Press Complaints Commission, freedom of the press and standards. At the last count three parliamentary committees are looking into the issue, listening to academics and former editors opine ad infinitum about “co-regulation”, “enhanced regulation”, “self-regulation” and “statutory regulation”.

Most of the time, however, the people who matter are silent or surly. Present-day tabloid and middle-market editors seem to have convinced themselves that the hacking scandal is a bit of a diversionary tactic by the government, and that, aside from a few technical changes here and there, it will blow over in time. Keep calm and carry on.

An atmosphere of denial permeated the recent Society of Editors conference. On the issue of phone hacking, many simply did not engage, beyond saying that the guilty will be punished and we will all move on. We have moved on … to the Royal Courts of Justice, and it does not make for a pleasant spectacle.

The first two days of victims’ hearings at Leveson have been enervating. From the quiet dignity of Milly Dowler’s parents to the fragile suffering of Mary-Ellen Field – sacked by Elle Macpherson, who wrongly suspected her of feeding the press – those who have suffered at the hands of the phone hackers have illustrated the bullying and the snooping of the hacks.Margaret and Jim Watson saw a child die as a result. Others had gone through breakdowns.

Their heart-rending testimony was somewhat overshadowed by Hugh Grant’s angry exchanges, his accusations against the Mail on Sunday, and the subsequent war of words among the lawyers. The more studied performance of comedian Steve Coogan this afternoon, including damning testimony against Andy Coulson, the prime minister’s former head of communications, was piercingly effective.

All the while Leveson has sat largely in silence, absorbing the magnitude of the task he has taken on. He has to find a way to prevent future criminality; to help create a new body that can regulate and punish quickly and effectively, and come up with guidelines on privacy that leave the private individual in peace but allow the press to expose the hypocritical. He needs to defend free expression and reinforce good investigative journalism that already faces a host of restrictions. He must try not to hasten the economic decline of an industry that is adopting increasingly desperate measures to keep itself afloat.

From everything I’ve seen of Leveson and those advising him, he gets it. Of course, caution is in order. Memories turn to the Hutton inquiry. The sharp questioning from the presiding judge then lulled everyone into a false sense of security. Hutton’s report was a shocker, a whitewash for government that opened the door to the emasculation of the BBC. And Leveson knows his recent history.

Yet those who need him most – the tabloids – are not helping him. By hiding or lashing out against their critics, the editors, proprietors and their legal teams are playing into the hands of the many voices calling for strict controls. Anyone who has sat before a parliamentary committee knows that the default position of MPs and peers is to hit back at the “beasts” in the media.

This is reflected in ministers’ positions. Kenneth Clarke, the justice secretary, told the Society of Editors not to underestimate the “shocking effects” of recent revelations. Later that day, Dominic Grieve, the attorney general, served warning about a government clampdown on contempt of court. He has since acted on his threat.

The PCC, under its new chairman, is looking at its own future. It aims to submit a detailed report to Leveson in the spring. By the nature of its constitution, it depends on the constructive engagement of its members. The more they resist, the more churlish their involvement with Leveson, the worse for the tabloids will be the result.

For a small army of celebrities the demise of the papers they loathe will be a cause for celebration. Yet the narrowing of a media discourse to an elite talking to an elite, through three or four “quality” papers, will ill serve freedom of expression and democracy. It is not too late for the tabloids to get real. Their obduracy is furrowing Leveson’s brow – and narrowing his room for manoeuvre.

John Kampfner is chief executive of Index on Censorship. He’s on twitter @johnkampfner

This article was first published in the Guardian

Nothing titillates journalists more than talking about their profession or, should I call it, their trade. The Leveson inquiry has spawned almost daily public discussions about the future of the Press Complaints Commission, freedom of the press and standards. At the last count three parliamentary committees are looking into the issue, listening to academics and former editors opine ad infinitum about “co-regulation”, “enhanced regulation”, “self-regulation” and “statutory regulation”.

Most of the time, however, the people who matter are silent or surly. Present-day tabloid and middle-market editors seem to have convinced themselves that the hacking scandal is a bit of a diversionary tactic by the government, and that, aside from a few technical changes here and there, it will blow over in time. Keep calm and carry on.

An atmosphere of denial permeated the recent Society of Editors conference. On the issue of phone hacking, many simply did not engage, beyond saying that the guilty will be punished and we will all move on. We have moved on … to the Royal Courts of Justice, and it does not make for a pleasant spectacle.

The first two days of victims’ hearings at Leveson have been enervating. From the quiet dignity of Milly Dowler’s parents to the fragile suffering of Mary-Ellen Field – sacked by Elle Macpherson, who wrongly suspected her of feeding the press – those who have suffered at the hands of the phone hackers have illustrated the bullying and the snooping of the hacks.Margaret and Jim Watson saw a child die as a result. Others had gone through breakdowns.

Their heart-rending testimony was somewhat overshadowed by Hugh Grant’s angry exchanges, his accusations against the Mail on Sunday, and the subsequent war of words among the lawyers. The more studied performance of comedian Steve Coogan this afternoon, including damning testimony against Andy Coulson, the prime minister’s former head of communications, was piercingly effective.

All the while Leveson has sat largely in silence, absorbing the magnitude of the task he has taken on. He has to find a way to prevent future criminality; to help create a new body that can regulate and punish quickly and effectively, and come up with guidelines on privacy that leave the private individual in peace but allow the press to expose the hypocritical. He needs to defend free expression and reinforce good investigative journalism that already faces a host of restrictions. He must try not to hasten the economic decline of an industry that is adopting increasingly desperate measures to keep itself afloat.

From everything I’ve seen of Leveson and those advising him, he gets it. Of course, caution is in order. Memories turn to the Hutton inquiry. The sharp questioning from the presiding judge then lulled everyone into a false sense of security. Hutton’s report was a shocker, a whitewash for government that opened the door to the emasculation of the BBC. And Leveson knows his recent history.

Yet those who need him most – the tabloids – are not helping him. By hiding or lashing out against their critics, the editors, proprietors and their legal teams are playing into the hands of the many voices calling for strict controls. Anyone who has sat before a parliamentary committee knows that the default position of MPs and peers is to hit back at the “beasts” in the media.

This is reflected in ministers’ positions. Kenneth Clarke, the justice secretary, told the Society of Editors not to underestimate the “shocking effects” of recent revelations. Later that day, Dominic Grieve, the attorney general, served warning about a government clampdown on contempt of court. He has since acted on his threat.

The PCC, under its new chairman, is looking at its own future. It aims to submit a detailed report to Leveson in the spring. By the nature of its constitution, it depends on the constructive engagement of its members. The more they resist, the more churlish their involvement with Leveson, the worse for the tabloids will be the result.

For a small army of celebrities the demise of the papers they loathe will be a cause for celebration. Yet the narrowing of a media discourse to an elite talking to an elite, through three or four “quality” papers, will ill serve freedom of expression and democracy. It is not too late for the tabloids to get real. Their obduracy is furrowing Leveson’s brow – and narrowing his room for manoeuvre.

John Kampfner is chief executive of Index on Censorship. He’s on twitter @johnkampfner

To mark the inaugural International Day to End Impunity on 23 November, join Index in demanding justice for journalists’ murdered in the line of duty

To mark the inaugural International Day to End Impunity on 23 November, join Index in demanding justice for journalists’ murdered in the line of duty

Freedom of Expression Organisations Call for Justice on International Day to End Impunity

London, November 23, 2011

Today Index on Censorship, Article 19, the Committee to Protect Journalists and English PEN join dozens of freedom of expression organisations around the world to mark the inaugural International Day to End Impunity.

In the past 10 years, more than 500 journalists have been killed. In nine out of 10 cases, the murderers have gone free. Many others targeted for exercising their right to freedom of expression — artists, writers, musicians, activists — join their ranks.

On this day two years ago the single deadliest event for the media took place when 30 journalists and two support workers were brutally killed in Ampatuan, Maguindanao province, The Philippines. The journalists were part of a convoy accompanying supporters of a local politician filing candidacy papers for provincial governor. In total the “Maguindanao Massacre” as it has come to be known, claimed 58 victims. Not one of more than a hundred individuals suspected of involvement in the atrocity has been convicted yet.

We join those in the Philippines not only in honouring their slain colleagues, friends and family members, but demanding justice for them and hundreds more in Russia, Belarus, Pakistan, Sri Lanka, Mexico, Colombia, Iraq and Somalia and other countries where killings of journalists and free expression activists have repeatedly gone unpunished. Above all we demand an end to the cycle violence and impunity.

This year alone at least 17 journalists were murdered for their work. These include Pakistani journalist Saleem Shahzad, whose body was found May 31 showing signs of torture. They include Mexican journalist and social media activist Maria Elizabeth Macías Castro Macías, whose killers left a computer keyboard and a note with the journalist’s body saying she had been killed for writing on social media websites. These heinous acts not only silence the messenger, but are intended to intimidate all others from bringing news and sharing critical voices with the public.

We call on governments around the world to investigate and prosecute these crimes and bring an end to impunity.

Article 19 English PEN

Committee to Protect Journalists Index on Censorship

1 November: Mohammad Ismail

2 November: José Bladimir Antuna Garcían

3 November: Abdul Razzak Johra

4 November: Laurent Bisset

5 November: Carlos Alberto Guajardo Romero

6 November: Wadallah Sarhan

7 November: Ahmed Hussein al-Maliki

8 November: Francisco Castro Menco

9 November: Dilip Mohapatra

10 November: Misael Tamayo Hernández

11 November: Johanne Sutton, Pierre Billaud and Volker Handloik

12 November: Gene Boyd Lumawag

13 November: José Armando Rodríguez Carreón

14 November: Seif Yehia and Ibraheem Sadoon

15 November: Fadia Mohammed Abid

16 November: Olga Kotovskaya

17 November: Meher-un-Nisa

18 November: Tara Singh Hayer

19 November: Eenadu-TV staff

20 November: Namik Taranci

21 November: Ram Chander Chaterpatti

22 November: Raad Jaafar Hamadi

23 November: Ampatuan massacre victims

23 November marks the anniversary of the 2009 Ampatuan massacre, in which 34 journalists were murdered in an election-related killing in the Philippines, making it the single deadliest incident for journalists in recent history.