Index relies entirely on the support of donors and readers to do its work.

Help us keep amplifying censored voices today.

Several reports yesterday and today suggest that police will have baton rounds “available” to them at the student demonstration planned for 9 November.

This has led to some outrage. The Guardian got this absurd quote from Green Party London Assembly member Jenny Jones:

Any officer that shoots a student with a baton round will have to answer to the whole of London. How did we come to this? An unpopular government pushing ahead with policies that are all pain and no gain, relying on police armed with plastic bullets to deal with young people who complain about it all. The prospect of the police shooting at unarmed demonstrators with any kind of bullet is frankly appalling, un-British and reminiscent of scenes currently being used by murderous dictatorships in the Middle East.

This is a bizarre and wrongheaded comparison. To suggest that the possibility of baton rounds being used on protesters in London is somehow the same as the fact of tank shells being fired at protesters in Homs is insulting to people standing against genuine tyranny, as opposed to an “unpopular government”.

Then there is the idea that plastic bullets are somehow “un-British”, which will be news to the people of Northern Ireland, both the ones who identify as British and those who don’t.

Meanwhile, Chavs author Owen Jones has tweeted that the police are using “threats about rubber bullets” in an attempt to “intimidate protesters”. Jones fails to identify what exactly the “threat” is.

In fact, if one examines the language of the Metropolitan Police statement, what we are dealing with is a contingency rather than a threat. This from the BBC:

In a statement, Scotland Yard said rubber bullets – also known as baton rounds – were “carried by a small number of trained officers”, none of whom would be patrolling the route of the march.

“This tactic requires pre-authority, and would take time to deploy, and is one of a range of tactics we have had available for public order, and not used, in the past.”

The story seems to have first emerged on London radio station LBC yesterday. But it is really not a story at all, or at least not a development. The Metropolitan Police have always had the capacity to use rubber bullets, and chosen not to do so.

If it is the case that an LBC reporter contacted the police to ask them if plastic bullets were part of the police’s arsenal to deal with disturbance, it would have been wrong of the police to deny this was the case. But this is very, very different from saying they would be used, and indeed counterintuitive to Met tactics on protest. Plastic bullets are not very useful for containment, which is the Metropolitan Police’s current method of dealing with protesters. Containment (including “kettling”) involves close quarters engagement with protesters, circumstances in which, again, the use of plastic bullets would be absurd (and absurdly dangerous to all parties).

Perhaps the police should be clearer on their tactics and arsenal, but those who claim to be on the side of the protesters should be careful not to create unnecessary tension.

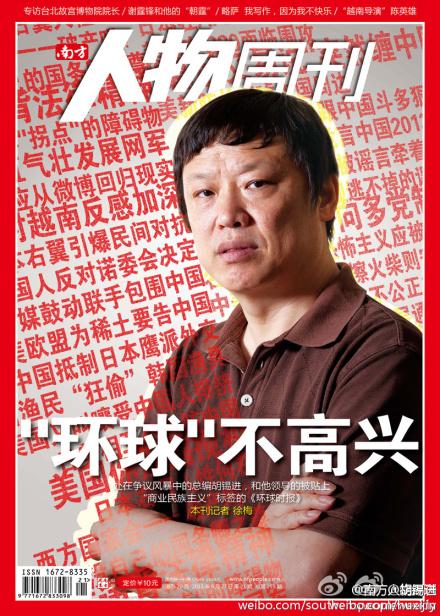

One of the most curious newspapers to come out of China in recent years is the English-language edition of the Global Times.

Owned by the People’s Daily group, it is one of only two national papers published in English in mainland China, alongside the long-standing, less sensational China Daily.

When the tabloid was launched by editor-in-chief Hu Xijin in 2009, Westerners hired as editors were told their aim was to steal China Daily’s readership by covering stories its rival and the rest of the domestic media would not dare cover. Hu has certainly kept his promise: over the years the paper has touched on the 1989 Tiananmen Square massacre, the detention earlier this year of dissident artist Ai Weiwei (including an exclusive interview with Ai on his release), and the house arrest of blind human rights lawyer Chen Chuangcheng. Its tone moves between hyper-nationalism and a more objective reflection on typically “sensitive” topics.

When the tabloid was launched by editor-in-chief Hu Xijin in 2009, Westerners hired as editors were told their aim was to steal China Daily’s readership by covering stories its rival and the rest of the domestic media would not dare cover. Hu has certainly kept his promise: over the years the paper has touched on the 1989 Tiananmen Square massacre, the detention earlier this year of dissident artist Ai Weiwei (including an exclusive interview with Ai on his release), and the house arrest of blind human rights lawyer Chen Chuangcheng. Its tone moves between hyper-nationalism and a more objective reflection on typically “sensitive” topics.

The Global Times is now so notorious among Western journalists that the paper itself has become a news story. Last week, Foreign Policy dubbed it “China’s Fox news“. The Global Times quickly responded with its own editorial saying: “the quality of the article didn’t live up to what we expect from the Western media.” Touché!

In order to find out more about the man, and the tabloid he has created, Index went behind the scenes to talk to Western editors and reporters at the tabloid. Because staff are forbidden to discuss the paper with Western media, we cannot disclose their names.

Their comments cast Hu as enthusiastic character who enjoys controversy and has a thing for Chinese film star Gong Li. Here’s a selection.

REPORTER A

I rather liked him… I think of him as a William Randolph Hearst [Citizen Kane] of Chinese journalism. He’s an excitable boy, a rakish liar. He loves to hear himself hold forth and says his biggest regret is not seeing enough of his teenage daughter because he works so late. He has a vintage poster of Gong Li in his modestly-appointed office. No other real decorations.

He knows really very little about US foreign or political policies but is very quick to jump on the idea that US is itching to drop a bomb or two on China.

He loves controversy and courts it — whether it’s an editorial in the Wall Street Journal or New York Times or Financial Times quoting Global Times for some addled hysterical stance or some trouble with the more conservative People’s Daily types.

He’s also a hypocrite, of course. He had a reporter [called Wen Tao] fired for tweeting from an all-Chinese news meeting where he had assured the staff that Global Times would print anything without fear or favour. That reporter later found a gig as an assistant for Ai Weiwei and was arrested with him, before being released at about the same time Ai was.

EDITOR B

What most people don’t realise about the paper unless they have the hard copy in front of them is that whenever a sensitive news story is covered, they always run an editorial with the official line to balance it out. So, for example when Ai Weiwei was arrested they ran the story of his arrest and then, as if to cover their backs, they ran that famous and oft-quoted opinion piece.

EDITOR C

He has a vision. He knows what he’s doing and he knows his audience. I think he wants to make Chinese journalism relevant and that’s why he is inflammatory on purpose. It really is sabre-rattling.

In China you can’t get away from top-down journalism. Criticism can only be levelled at lower officials, you can’t go any higher.

And these criticisms give the illusion that the Global Times is impartial. Hu wants these to give the paper credibility.

Yes, he’s taking a lot of cues from Fox News. He’s learnt how to prod his readership, to rally them.

Hu is always smiling, but he shouts at a lot at the Chinese staff, and forbids them from talking to the foreign press.

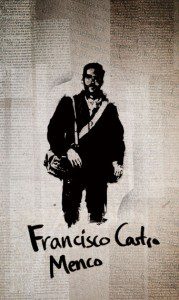

MURDERED 8 NOVEMBER 1997

MURDERED 8 NOVEMBER 1997

Francisco Castro Menco, President, Fundación Cultural — Majagual, Colombia

Join us in demanding justice for Francisco Castro Menco, murdered on 8 November 1997. A candidate for the departmental assembly, and president of the Fundación Cultural, a community foundation that ran daily radio broadcasts in the violence-ridden town of Majagual, Sucre.

While Castro tried to make the Fundación Cultural a neutral forum for community news, it represented an independent voice in a region where both armed guerrillas and paramilitary forces are active. Castro hosted a daily programme on community affairs and often called for an end to the violence. Local journalists believe he was murdered because of his appeals for peace but were unsure if guerrillas or the paramilitaries were responsible.

International Day to End Impunity is on 23 November. Until that date, we will reveal a story each day of a journalist, writer or free expression advocate who was killed in the line of duty.

A group of petitioners attempting to visit blind Chinese activist Chen Guangcheng were beaten on 30 October. According to petitioner Zhu Jindi, as the group of 37 supporters made their way to Dongshigu in Shandong province, where Chen remains under illegal house arrest, 100 people appeared and beat the group, confiscating their mobile phones and cameras. Li Yu, a democracy activist from Sichuan, was severely beaten and thrown into a police car with two other petitioners. Li is still missing, though the other two individuals were released on 2 November. Other activists have reported similar incidents when attempting to visit Chen, who fell foul of authorities in 2005 for his work in exposing forced abortions in Shandong province.