After a year of political unrest following the Arab Spring, Iona Craig reports on the current situation in Yemen.

After a year of political unrest following the Arab Spring, Iona Craig reports on the current situation in Yemen.

Open criticism of Yemen’s President, Ali Abdullah Saleh, on the streets of the capital Sana’a was rare before last year. Those brave enough to speak out against the three-decade-old regime would often blame those around the veteran leader, while excluding Saleh from the faults of corruption and nepotism.

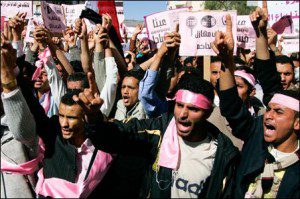

As events unfolded in Tunisia and Egypt in January 2011 and mass protests spread to the Arabian Peninsula. Slowly people started finding their voice. Although in early February, anti-government protests had been ongoing for several days, there was a feeling of safety in numbers and solidarity amongst the attendees of mass demonstrations.

But in those early weeks, I watched a youth protester become embroiled in a furious debate on a public bus in Sana’a. The youth sparred with an elderly man who had lived through Yemen’s civil war of the 1960s and witnessed the fall of the Imamate, and many moved away from the young student as he raged over the heads of passengers about Yemen’s long standing leader. Others looked on nervously before the driver demanded the youth’s silence. He refused, deciding instead to disembark rather than submit. The brief but vociferous exchange left the remaining occupants in stunned silence. From these small beginnings and expression of years of frustration, Yemen’s revolution and a year of political unrest grew.

Compared to its regional neighbours, pre-2011 Yemenis enjoyed relative freedom. Multiple political opposition parties existed, a small but unwavering independent press operated in contrast to the state media and the multiple government aligned newspapers. Despite this apparent tolerance, when the protest movement took off after the fall of Egypt’s President Mubarak on February 11, Yemeni journalists covering demonstrations calling for the end of Saleh’s 33-year rule, were amongst the first victims of a campaign of intimidation and attacks. Six journalists were killed during last year’s violence, more than any other country caught up in the Arab Spring, according to International Press Institute figures. Between 1994 and 2008, nine Yemeni journalists were killed in mysterious car accidents or other questionable accidental deaths .

But since a new unity government — including new heads of the Ministry of Information and Ministry for Human Rights — formed last month, following Saleh’s signing of a Gulf and UN-brokered transfer of power deal in November, Yemen’s media has experienced a significant shift. The staunch support for Saleh and his General People’s Congress party across the state media has changed dramatically. For the first time pictures of anti-government demonstrations were run on the front page of government aligned newspapers, whilst the Ministry of defence weekly newspaper, 26 September, printed accusations of corruption against its own editor, marking a new phase in protests across the country.

In December, separate to, but emboldened by 12 months of anti-government demonstrations, civil servants and workers at government institutions began their own small but in several cases effective demonstrations , civil servants and workers at government institutions began their own small but in several cases effective demonstrations – anti-corruption rallies. Labelled Yemen’s “parallel revolution” from Sana’a police headquarters to the coast guard in Aden workers have gone out on strike demanding the removal of corrupt bosses. The latest ongoing walkout by members of Yemen’s air force began on January 22, disrupting flights at Sana’a airport, which also acts as Yemen’s main air force base, as protesting airmen demanded the removal of the air force chief, also President Saleh’s half-brother, Mohammed Saleh al-Ahmer. The mutiny has reportedly spread to three more airbases across the country. The Yemeni people have found their voice and the power of peaceful protest as a way of expressing not only their dissatisfaction against the outgoing president Saleh — who left the country on 22 January for medical treatment in the US — but are having a real impact in the removal of several officials.

The Gulf and UN-brokered deal, which is now being implemented, falls short of most people’s expectations, in particular the immunity law passed by parliament last weekend that gives protection from prosecution to Saleh for “politically motivated crimes” and all those acting for him “in their official capacity.” The bill was described by Human Rights Watch as unlawful and “an affront to victims and a blow to justice.” Next month’s election should be an historic moment in a country where nearly two generations have only known one leader. But the election of Vice-President Abdrabbu Mansour Hadi is a formality rather than a diplomatic process to finally remove Mr Saleh from office. After a year of political unrest and with the military and air force still under the control of Saleh’s sons, nephews and extended family members , his influence has yet to end, and Yemen’s future remains uncertain.

Crucially the transition initiative excludes three isolated groups: the pre-existing Southern Movement and their demand for secession, the northern Houthi rebels, calling for autonomy, who have fought six wars against the government since 2004, in addition to the 2011 protest movement.

2011 in Yemen will not only be remembered as a year of blood shed and turmoil and the year a Yemeni activist , Tawakkol Karman, became the first female from the Arab world to win a Nobel Peace Prize, but also for a notable and seemingly irreversible shift: Yemenis are no longer willing to accept years of endemic corruption throughout the state system. As the country moves into a two year period of transition, ahead of parliamentary elections in 2014, it will be up Yemenis external to the political process to maintain pressure on the unity government and politicians in order for any real change to take place.

Iona Craig is a freelance journalist based in Sana’a