Censorship in Pakistan has ranged from the ridiculous to the downright terrifying. But as the country entered a new phase in 1983, Salman Rushdie hoped for change

Censorship in Pakistan has ranged from the ridiculous to the downright terrifying. But as the country entered a new phase in 1983, Salman Rushdie hoped for change

My first memories of censorship are cinematic: screen kisses brutalised by prudish scissors which chopped out the moments of actual contact. (Briefly, before comprehension dawned, I wondered if that were all there was to kissing, the languorous approach and then the sudden turkey-jerk away.) The effect was usually somewhat comic, and censorship still retains, in contemporary Pakistan, a strong element of comedy. When the Pakistani censors found that the movie El Cid ended with a dead Charlton Heston leading the Christians to victory over live Muslims, they nearly banned it until they had the idea of simply cutting out the entire climax, so that the film as screened showed El Cid mortally wounded. El Cid dying nobly, and then it ended. Muslims 1, Christians 0.

The comedy is sometimes black. The burning of the film Kissa Kursi Ka [Tale of a Chair] during Mrs Gandhi’s Emergency rule in India is notorious; and, in Pakistan, a reader’s letter to the Pakistan Times, in support of the decision to ban the film Gandhi because of its unflattering portrayal of MA Jinnah, criticised certain “liberal elements” for having dared to suggest that the film should be released so that Pakistanis could make up their own minds about it. If they were less broad-minded, the letter writer suggested, these persons would be better citizens of Pakistan.

My first direct encounter with censorship took place in 1968, when I was 21, fresh out of Cambridge and full of the radical fervour of that famous year. I returned to Karachi where a small magazine commissioned me to write a piece about my impressions on returning home. I remember very little about this piece (mercifully, memory is a censor, too), except that it was not at all political. It tended, I think, to linger melodramatically on images of dying horses with flies settling on their eyeballs. You can imagine the sort of thing. Anyway, I submitted my piece, and a couple of weeks later was told by the magazine’s editor that the Press Council, the national censors, had banned it completely. Now it so happened that I had an uncle on the Press Council, and in a very unradical, string-pulling mood I thought I’d just go and see him and everything would be sorted out. He looked tired when I confronted him. “Publication,” he said immovably, “would not be in your best interests.” I never found out why.

Next I persuaded Karachi TV to let me produce and act in Edward Albee’s The Zoo Story, which they liked because it was 45 minutes long, had a cast of two and required only a park bench for a set. I then had to go through a series of astonishing censorship conferences. The character I played had a long monologue in which he described his landlady’s dog’s repeated attacks on him. In an attempt to befriend the dog, he bought it half a dozen hamburgers. The dog refused the hamburgers and attacked him again. “I was offended,” I was supposed to say. “It was six perfectly good hamburgers with not enough pork in them to make it disgusting.”

“Pork”, a TV executive told me solemnly, “is a four-letter word.” He had said the same thing about “sex”, and “homosexual”, but this time I argued back. The text, I pleaded, was saying the right thing about pork. Pork, in Albee’s view, made hamburgers so disgusting that even dogs refused them. This was superb anti-pork propaganda. It must stay. “You don’t see”, the executive told me, wearing the same tired expression as my uncle had, “the word pork may not be spoken on Pakistan television.” And that was that. I also had to cut the line about God being a coloured queen who wears a kimono and plucks his eyebrows. The point I’m making is not that censorship is a source of amusement, which it usually isn’t, but that –– in Pakistan, at any rate –– it is everywhere, inescapable, permitting no appeal. In India the authorities control the media that matter — radio and television — and allow some leeway to the press, comforted by their knowledge of the country’s low literacy level. In Pakistan they go further. Not only do they control the press, but the journalists too. At the recent conference of the Non-Aligned Movement in New Delhi, the Pakistan press corps was notable for its fearfulness. Each member was worried that one of the other guys might inform on him when they returned — for drinking, for instance, or consorting too closely with Hindus, or performing other unpatriotic acts. Indian journalists were deeply depressed by the sight of their opposite numbers behaving like scared rabbits one moment and quislings the next.

The danger of suppression

What are the effects of total censorship? Obviously, the absence of information and the presence of lies. During Mr Bhutto’s campaign of genocide in Balochistan, the news media remained silent. Officially, Balochistan was at peace. Those who died, died unofficial deaths. It must have comforted them to know that the State’s truth declared them all to be alive. Another example: you will not find the involvement of Pakistan’s military rulers with the booming heroin industry much discussed in the country’s news media. Yet this is what underlies General Zia’s concern for the lot of the Afghan refugees. It is Afghan free enterprise that runs the Pakistan heroin business, and they have had the good sense to make sure that they make the army rich as well as themselves. How fortunate that the Quran does not mention anything about the ethics of heroin pushing.

But the worst, most insidious effect of censorship is that, in the end, it can deaden the imagination of the people. Where there is no debate, it is hard to go on remembering, every day, that there is a suppressed side to every argument. It becomes almost impossible to conceive of what the suppressed things might be. It becomes easy to think that what has been suppressed was valueless, anyway, or so dangerous that it needed to be suppressed. And then the victory of the censor is total. The anti-Gandhi letter writer who recommended narrow-mindedness as anational virtue is one such casualty of censorship; he loves Big Brother — or Burra Bhai , perhaps.

It seems, now, that General Zia’s days are numbered. I do not believe that the present disturbances are the end, but they are the beginning of the end, because they show that the people have lost their fear of his brutal regime, and if the people cease to be afraid, he is done for. But Pakistan’s big test will come after the end of dictatorship, after the restoration of civilian rule and free elections, whenever that is, in one year or two or five; because if leaders do not then emerge who are willing to lift censorship, to permit dissent, to believe and to demonstrate that opposition is the bedrock of democracy, then, I am afraid, the last chance will have been lost. For the moment, however, one can hope.

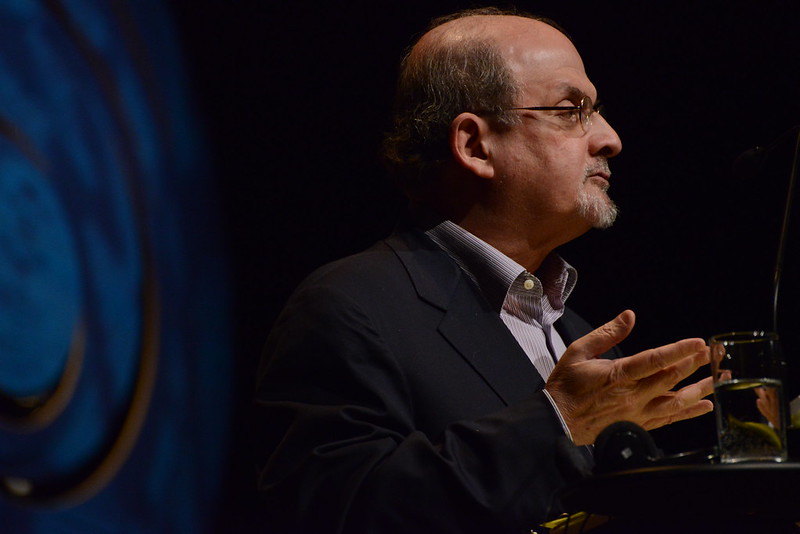

Salman Rushdie’s latest novel is Luka and the Fire of Life. This article was first published in Index on Censorship Volume 11 Number 6