The online retailer has been criticised for profiting from ebooks featuring terror and violence. No one should tell us what to read, says Jo Glanville

The online retailer has been criticised for profiting from ebooks featuring terror and violence. No one should tell us what to read, says Jo Glanville

This article was originally publised at Comment is Free

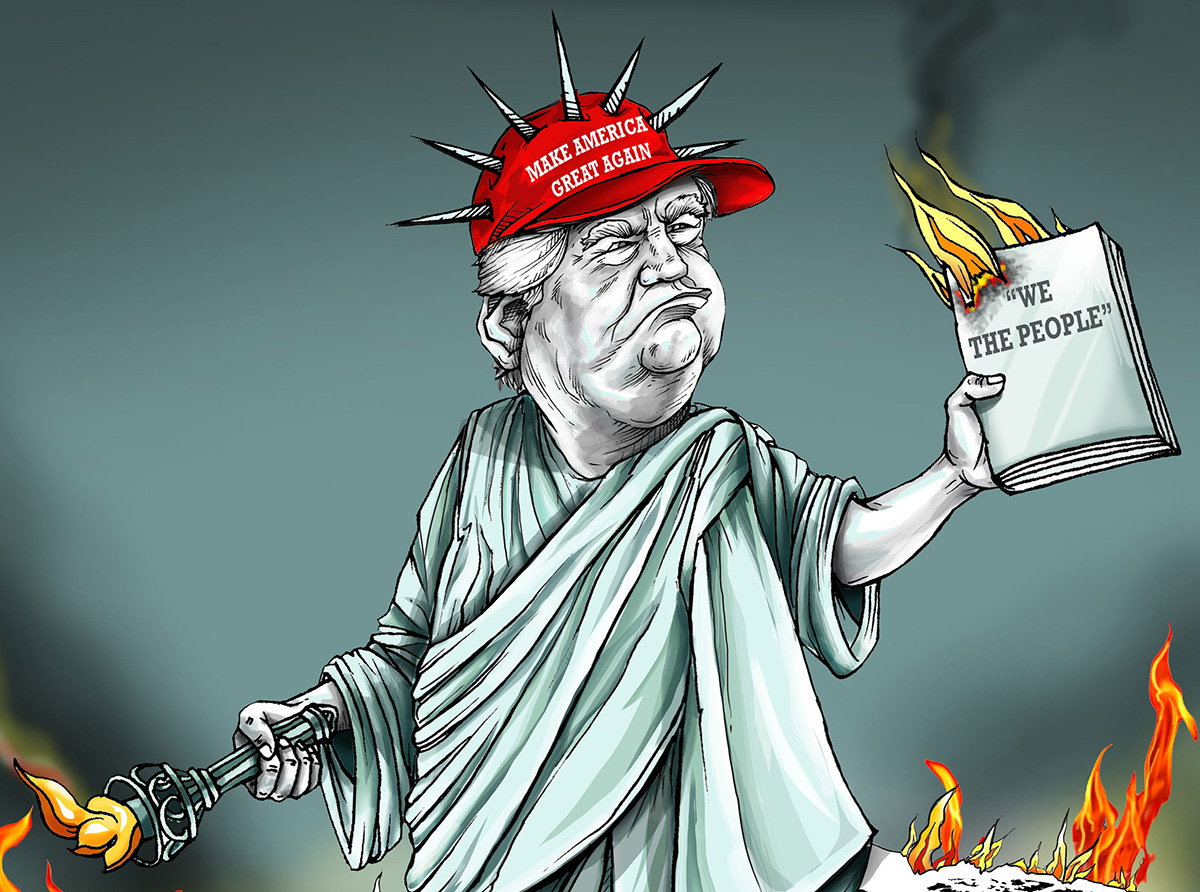

Amazon is under fire again, this time for profiting from ebooks on terror, hate and violence. The Muslim Council of Britain has called on Amazon to take “proper responsibility” for the content of books on its site, with one ebook on sale reportedly including images of the Qur’an being burned and a woman being hanged.

All booksellers make money out of books featuring terror or violence whether it’s Homer’s Iliad or JG Ballard’s Crash — but virtual booksellers appear to present a new threat to public morality. Once upon a time, we could rely on traditional publishers to make sound editorial decisions to publish obscenity and gore, now anyone can do it.

The last time Amazon faced an outcry, over a book on paedophilia, it initially defended its actions with some gumption, stating that it was censorship not to sell certain books simply because we or others believe their message was objectionable and that it supported the right of every individual to make their own purchasing decisions. Ultimately, however, the book was withdrawn. A month later, Amazon was reported as having removed incest-themed erotica from its Kindle store. This was the same period in which it pulled WikiLeaks, arguing that the website was in breach of its terms of service and was putting human rights workers at risk.

Amazon’s inconsistency has made it more vulnerable to pressure. Its own guidelines on offensive material state that “what we deem offensive is probably about what you would expect“, which is almost as helpful as the famous US supreme court judgment nearly 50 years ago on hardcore pornography, “I know it when I see it“. While such vagueness may give a wide latitude for freedom of expression, it also means that when there’s enough moral outrage, it may be difficult for Amazon to resist caving in.

Clearer guidelines are needed to protect free speech online and that should include material that causes offence. Expecting virtual booksellers, hosts and publishers to operate as taste and decency police would introduce unaccountable censorship based on subjective criteria. The best-selling erotica Fifty Shades of Grey, which began life on fan-fiction websites, and was first published as an ebook and print-on-demand paperback, might well have failed such a test and deprived the world of the delights of mummy porn.

The famous obscenity trials of the 60s and 70s were only in rare cases about protecting great literature – it was the right to freedom of expression that was at stake, whatever the quality of the content. Shortly before he died, the great writer and barrister John Mortimer (who defended the most celebrated obscenity cases of the time) recalled his famous defence of the editors of Oz magazine in an interview for Index on Censorship. An Oz issue edited by school children was prosecuted under the Obscene Publications Act in 1971; particular offence was caused by a cartoon of a sexually active Rupert Bear. “We weren’t defending anything with any particular merit,” Mortimer told me. “We were defending a principle, I suppose, that you shouldn’t have any censorship, that nobody should tell you what to read or write. It’s entirely your own business.” He believed that it was a principle that, a generation later, had been undermined.

Three years ago, there was an attempt to prosecute a civil servant under the Obscene Publications Act for publishing a violent sexual fantasy online about Girls Aloud. It described the rape, murder and mutilation of members of the pop group – no apparent literary merit here either, but a fantasy and not illegal. The defendant was cleared, but that wise decision hasn’t stopped the continuing skirmishes or the moral panic, which has been encouraged by the government.

The call for censorship and the expectation that online intermediaries police the internet are becoming regular demands. So it’s necessary to reassert that fundamental principle: the right to read anything we like.

Jo Glanville is editor of Index on Censorship magazine