Vladimir Putin says [Ru] he doesn’t use the internet very much. But he has definitely recognised its power. The biggest protest rallies in post-Soviet Russia, against Putin and his party United Russia, were organised online. No wonder that the parliamentary and presidential elections and Putin’s inauguration were all marked by the hacking of independent media websites and LiveJournal, Russia’s most popular blogging platform, via DDoS (distributed denial of service) attacks.

Russian television is poisoned by censorship, and there are few offline platforms for public discussion. That is why social networks and blogs provide the space people from all over Russia use to share ideas and plans protests against Putin.

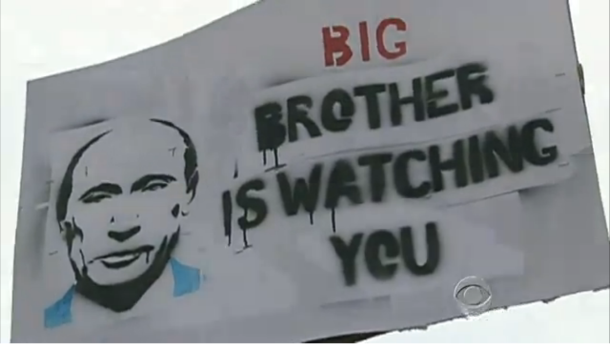

Russian protesters waved this banner during December 2011 protests. (Credit: CBS News video. Screenshot by CNET’s Jonathan Skillings)

The precedent of persecuting bloggers to silence them was set in 2008, a year after a blogger Savva Terentyev criticised police in a comment on a LiveJournal post he was sentenced to one year suspended sentence, article 282 of Russian Criminal Code for, “fomenting of social hatred” towards policemen. Since then, article 282, which covers actions provoking animosity and hatred towards certain religious, social, gender or national groups has been used to silence bloggers through the courts.

The other charge commonly used against internet users is “extremism” . Throughout Putin’s reign this charge has been used to target people who criticise the Kremlin — together with defamation and drug legislation. Russia’s Department of Presidential Affairs won three defamation lawsuits against newspaper Novaya Gazeta in just one week last year. All the articles talked about this authority’s controversial withdrawals from Russian budget and extremely high salaries of its staff. The editor-in-chief Dmitry Muratov told Index that Kremlin has been using defamation suits as a censorship instrument.

Taisia Osipova, the Other Russia activist, was sentenced to eight years in prison today on charges of drug trafficking. Rights activists has called her a political prisoner and connect her prosecution with political activism — her husband is a member of The Other Russia political council. No fingerprints were analysed with the drugs Osipova allegedly held in her flat, and the three witnesses in the case were pro-Kremlin youth movement members.

Sometimes an internet user doesn’t even have to criticise Putin to have his website shut down.In 2009 antiextremism legislation was misused to block an internet archive of historian Vyacheslav Rumyantsev after a request by St Petersburg police. The library contained a synopsis of Hitler’s Mein Kampf — along with Rumyantsev’s preface and comments, which explained how dangerous the book was. He wrote that it was important to know the “enemy’s ideology” to fully understand World War II. However, the police said he was promoting extremist materials, and the page was taken down.

Starting from 1 November 2012 Russian authorities won’t need a court ruling, like they did in the Terentyev case. Authorities will appeal to ISPs, like in the Rumyantsev case, create website blacklists and will be able to actually shut down anything they won’t like. Previously, a court ruling could make a website or the URL of a certain web content inaccessible in a specific region, while it stayed available in another.

Andrey Soldatov, an expert on Russian security services, notes that soon “the Kremlin will have at its disposal the facilities for blocking access to internet resources across the whole of Russia”, including Skype and Facebook.

That is the result of the activities of the State Duma this summer. The period after Putin returned to Kremlin will stay in Russians’ memory as a time of scandalous criminal prosecutions and controversial laws, which in spite of people’s protests were passed by the Duma.

The internet blacklist law, perhaps more than the other new laws — against rally organisers, NGOs which are financed from abroad, and the law which re-criminalised defamation — is likely to cause the saddest and the biggest consequences for Russian civil society.

Russian-language Wikipedia blacked out in protest of the draft law

The new law — “amendments to federal law on protecting children from information harmful to their health and development” stipulates Russian websites can be blocked without judicial decision. Here is the scheme: law enforcement authorities notify a host and/or telecom access provider that a website is blacklisted. Under the legislation this could be to block online drug and suicide promotion, porn, and the notorious “extremist materials”, but the vagueness of the definition means authorities can block anything they might consider “dangerous to the state”.

A government agency, not specified in the law, will inform a provider of the blacklisting of a website blacklisted. The provider, in his turn, then informs the website owner he must delete the controversial content. If the content is not removed within 24 hours the provider blocks either the URL of the particular material, or the domain name, or the whole IP address. If the provider doesn’t do the blocking, he shares responsibility with the website’s owner. Everything will stay on the blacklist forever, and the provider might be fined. For example, anyone will be able to sue him for moral damage he brought to one’s children (similar law suits were brought to court when Pussy Riot trial. Several people wanted money from them for “moral damage”)

The website’s owner then has three months to appeal against the blocking to the court. But it is not clear from the new law who will pay the legal expenses and compensate the owner for the lost profit (if his website brought in any profit).

The law was passed within just a couple of days, despite protests by opposition activists, the Presidential Human Rights Council, Russian Wikipedia, Yandex — the Russian popular web search engine, – and social network Vkontakte.ru — number two after Facebook in Russia. None of the protests made a difference to the Duma.

Internet companies spent August discussing the various federal actions needed for the law to be implemented, as it is still not clear who will be in charge of the blacklist. It is most likely to become the responsibility of Roskomnadzor — the Federal Surveillance Service for Mass Media and Communications. One of the other questions to be answered is whether the blacklist will be published. The federal enactment, clarifying the scandalous law, is expected to be passed in September.

Meanwhile Russian telecom companies have already started buying and testing special equipment for blocking websites. Such systems are expensive and effective and provide the ability to block anything at any time. Their use, as stated above, doesn’t need a court decision according to the new law.

The Kremlin has finally found a way to rein in something it couldn’t control for 12 years. But the measure, no matter how harmful it is for freedom of expression, may have come too late: thousands of Russians have already learned to shift their anger to the street.