South Africa’s parliament is in its final stages of reviewing a bill that, if passed, could have severe implications for press freedom in the country and the African continent. The Protection of State Information Bill (also known as the Secrecy Bill) could result in the imprisonment of journalists and whistleblowers who possess, publish or leak state secrets for up to 25 years.

Despite being amended over the last 18 months, the bill, introduced in 2010, has sparked condemnation from opposition MPs, writers, journalists and civil society groups. Speaking at an Index on Censorship event in March this year, South African Nobel prize-winning author Nadine Gordimer said the bill must “be discarded in its entirety”.

South Africa’s political party, the ANC, claims the bill will strengthen national security and is not aimed at muzzling the press. But for some the Bill is part of a wider assault by the ANC on press freedom. “The rhetoric of the ANC government has grown more hostile [towards the media] over the last few years,” Mohamed Keita, advocacy coordinator for the Africa programme at the New York-based Committee to Protect Journalists told Index. “The media in South Africa has on some occasions got it wrong but not for the majority of times. The government wants to focus on these few times to suggest it should be reined in and controlled. To use this as an excuse to blame all of the media and paint them all with one brush is too far.”

According to Murray Hunter, national coordinator of the Right2Know Campaign, a coalition of civil society groups promoting the right to access information and free expression, the bill will also have grave implications for people in the civil service considering blowing the whistle. “Where you see activists organising in communities and labelled risks to social stability, it is possible this bill will be used to silence people at a grassroots level,” he says.

“The threat is there that it provides the framework for an abuse of power,” he adds.

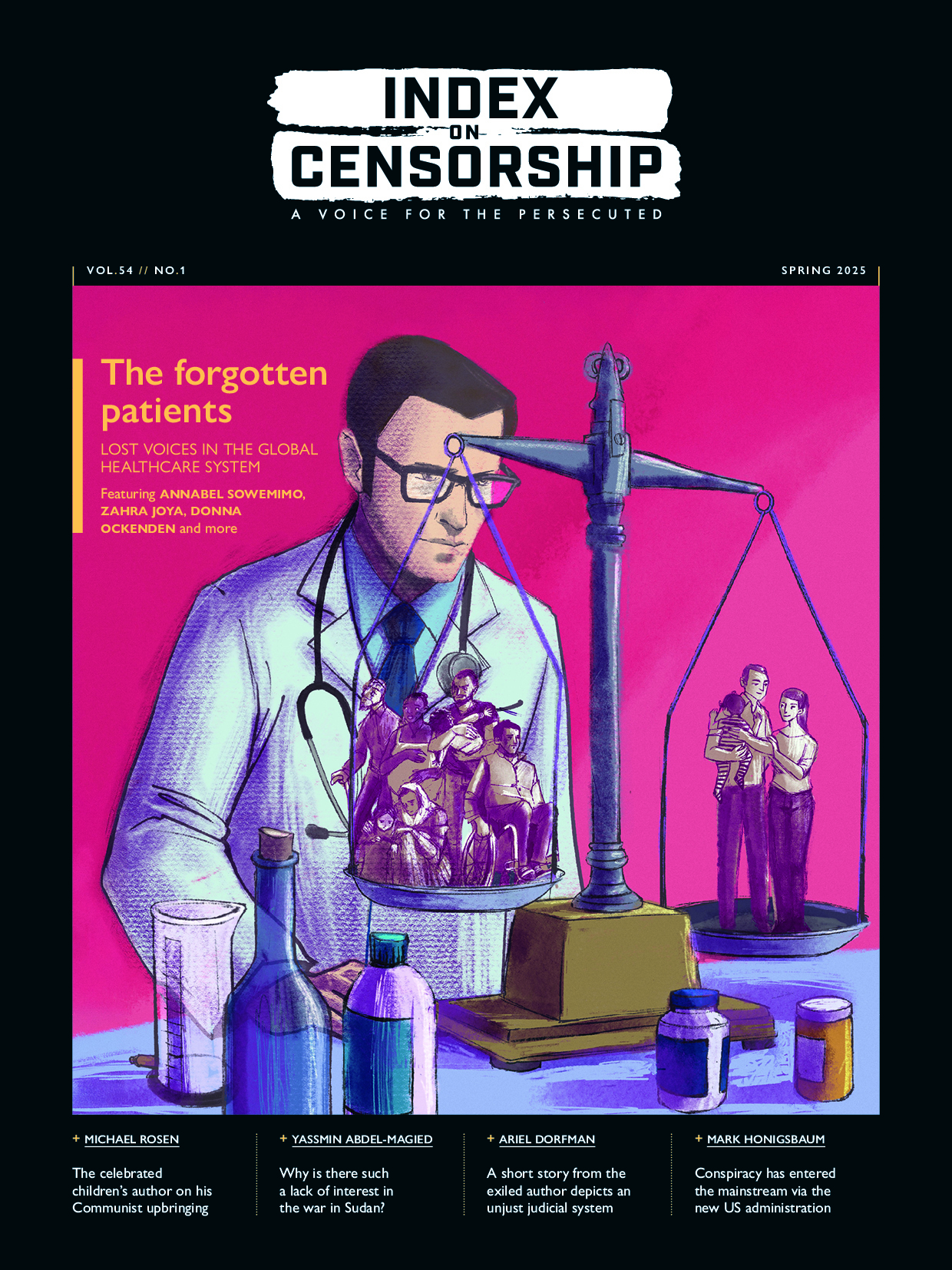

Protesters at a march against the Secrecy Bill in Cape Town, October 2010. Peter-John Freeman | Demotix

There are also concerns the bill could have continent-wide ramifications, given South Africa’s role in leading by example as a democracy. “There is concern among access to information activists that other governments are watching what has happened and might use it as an opportunity to pass similar legislation as a means of consolidating political power,” Hunter says.

According to Hunter, the bill is “desperately out of touch” with the way information flows in the 21st century. “In an era where it’s never been more possible for information to be free, this is a very old fashioned and brutal tool to protect state interests.”

But, while he argues the bill does speak to a broader pattern of clamping down on freedom of information in South Africa, Hunter contends it is not as clear-cut as an ANC-led attack on the media. “I’d paint the bill as part of a wider pattern of a securocrat elite within the ANC who are really pushing for greater powers for themselves,” he says, noting the bill in its original form granted hefty powers to the Department of State Security regarding what sort of information it can make public and the terms in which information can be kept secret.

Both Hunter and Keita argue the Bill will have a chilling effect on freedom of the press and freedom of expression in South Africa. Scoops from the past decade based on leaked documents that exposed corruption and bribery allegations and would never have hit the front pages if the law were in place.

Apartheid-era legislation also remains an issue. Hunter describes how last month South Africa’s Mail and Guardian newspaper began publishing damning investigations on upgrades to the presidential residences, but when they asked relevant government departments how much money was spent, they were told that information about presidential residence was protected by apartheid-era rules, and there was no obligation to reveal the costs.

Last week saw some progress, with Clause 49 of the bill, which would have given the Department of State Security even greater powers of secrecy, being struck down by the ANC during deliberations last Wednesday. In an apparent bid to “reduce opposition” to the bill, the ANC also proposed the removal of minimum sentences for divulging classified information.

But concerns remain, notably over the bill’s lack of a public interest defence. According to the Right2Know Campaign, the current ANC proposal for a limited public interest defence “only protects you if you can show that the disclosure ‘reveals criminal activity’. This means that vital information about the abuse of power, tender sleaze or other wrongdoing will remain under wraps.”

The campaign adds there are also loopholes in the definition of espionage, meaning a whistleblower, journalist or activist “may still be prosecuted under the “espionage”, “receiving state information unlawfully” or “hostile activity” clauses (36-38), or if the information was classified by the State Security Agency (clause 49).”

“In some ways the massive crisis of the secrecy bill is also enormously useful, as it has awakened many people to a broader trend of attacks on the free flow of information,” Hunter says. “In the last two years, because of the secrecy bill and victories on it, we’ve seen securocrats being pushed on to the back foot and massive gains made.”

“It’s not doom and gloom for me, this is one of the greatest moments in South Africa’s democracy,” says Hunter. “We all have the Department of State Security to thank for that. The fact the bill was so bad in its original form has been a massive opportunity.”

Marta Cooper is an editorial researcher at Index. She tweets at @martaruco