As four men go on trial in Denmark accused of planning an attack against newspaper Jyllands-Posten, Kenan Malik argues that since the Danish cartoon controversy free expression is now seen as an enemy of liberty

As four men go on trial in Denmark accused of planning an attack against newspaper Jyllands-Posten, Kenan Malik argues that since the Danish cartoon controversy free expression is now seen as an enemy of liberty

“I have definitely become a free speech fundamentalist,” says Flemming Rose. Perhaps that should not be surprising. It was, after all, Rose who helped launch the Danish cartoon controversy in 2005 as culture editor of the newspaper Jyllands-Posten. He had picked up on a story about the difficulties that children’s author Kåre Bluitgen had faced in finding an illustrator for a book he was writing on Islam. Every illustrator whom Bluitgen had contacted had been worried that he would end up like Theo van Gogh, the Dutch filmmaker ritually murdered on the streets of Amsterdam by a Muslim incensed by his anti-Islamic films. Rose wanted, he said, to see ‘how deep this self-censorship lies in the Danish public’. So he set a challenge to Danish cartoonists: draw a caricature of the Prophet Mohammed and we will publish a selection in Jyllands-Posten.

Rose approached 42 cartoonists, 12 of whom accepted the challenge. Their caricatures, including Kurt Westergaard’s infamous image of the prophet wearing a turban in the form of a bomb, were published in Jyllands-Posten on 30 September 2005. “The modern secular society,” Rose wrote in a commentary, “is rejected by some Muslims. They demand a special position, insisting on special consideration of their own religious feelings. It is incompatible with contemporary democracy and freedom of speech, where you must be ready to put up with insults, mockery and ridicule.”

To Rose’s critics, the very act of publishing the cartoons, and of provoking Muslims into a response, was irresponsible, even racist. In their eyes Rose has always been a “free speech fundamentalist”, and not in a good way. Not so, Rose told me. When he published the cartoons, he believed in free speech, but he did not have a deep understanding of the subject. It was the controversy itself that made him think about the real meaning of freedom of expression, and challenged many of his preconceptions.

The Satanic Verses: new debate, new kinds of violence

The contemporary debate about free speech has been shaped by two key confrontations over the past two decades. The first was the Salman Rushdie affair, the second the Danish cartoons controversy. The controversy over The Satanic Verses was a cultural and political watershed, the storm through which many of the issues that have become the defining problems of our age first emerged into popular consciousness –– the nature of Islam, and its relationship to the West, the meaning of multiculturalism, the fear of terrorism, the boundaries of tolerance in a liberal society, the limits of free speech in a plural world, and so on.

The contemporary debate about free speech has been shaped by two key confrontations over the past two decades. The first was the Salman Rushdie affair, the second the Danish cartoons controversy. The controversy over The Satanic Verses was a cultural and political watershed, the storm through which many of the issues that have become the defining problems of our age first emerged into popular consciousness –– the nature of Islam, and its relationship to the West, the meaning of multiculturalism, the fear of terrorism, the boundaries of tolerance in a liberal society, the limits of free speech in a plural world, and so on.

If the controversy over The Satanic Verses provided a glimpse of the world as it would come to be, the furore over the Danish cartoons helped lay bare the anatomy of the world as it had become. “The context was very different,” says Rose about the two controversies. “I followed the Rushdie affair, but at that time the big global story was the breakdown of communism in Eastern Europe.” The “debate about migration, integration and diversity” is very different now than it was in 1989, he believes, and “far more complex”.

Perhaps the biggest difference, however, between the Rushdie affair and the cartoons controversy lay less in the context than in the attitudes, particularly the attitudes of liberal intellectuals towards free speech and the idea of giving offence. In 1989 there had been much equivocation by politicians and intellectuals, but with one or two exceptions, such as John le Carré, who claimed that “there is no law in life or nature that says great religions may be insulted with impunity”, and Germaine Greer, who allegedly declared that “jail is a good place for writers”, no one seriously doubted Rushdie’s right to publish his novel. There was little equivocation over the Danish cartoons, just a widespread acceptance that Jyllands-Posten had been in the wrong, and even more so the newspapers and magazines that had republished the cartoons. Writers and artists, many insisted, had a responsibility to desist from giving offence and upsetting religious sensibilities.

“I understand your concerns,” Louise Arbour, the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights, told delegates at an Organisation of Islamic Conference summit in Mecca in 2005, “and would like to emphasise that I regret any statement or act that could express a lack of respect for the religion of others.” The European Union, too, expressed ‘regret’ about the publication of the cartoons. “These kinds of drawings can add to the growing Islamophobia in Europe,” claimed Franco Frattini, EU Commissioner for Justice, Freedom and Security. Former US President Bill Clinton condemned “these totally outrageous cartoons against Islam” and feared that anti-Semitism had been replaced by anti-Islamic prejudice.

The difference in attitudes revealed how the very landscape of free speech had been transformed. Peter Mayer had been CEO of Penguin, Rushdie’s publishers at the time of the fatwa. He talked publicly about those events in an interview he gave for my book From Fatwa to Jihad. Early on the morning of Valentine’s Day 1989, Mayer received a call from Patrick Wright, Penguin’s head of sales in London. Had he seen the headlines about the fatwa, Wright asked him. “What’s a fatwa?” asked a bemused Mayer. It was not just the idea of a fatwa that was new; neither Mayer nor Penguin had even begun to think about the issues that were soon to dominate their lives. “We had never had to have this kind of discussion before,” Mayer observed. “Today there is a constant stream of discussion about multiculturalism and minority rights and sharia law. Not then. We had never had to think about free speech or about why we were publishers.”

The fatwa ushered in not just a new kind of debate but a new kind of violence. Salman Rushdie was forced into hiding for almost a decade. Translators and publishers were assaulted and even murdered. In July 1991, Hitoshi Igarashi, a Japanese professor of literature and translator of The Satanic Verses, was knifed to death on the campus of Tsukuba University. That same month, another translator of Rushdie’s novel, the Italian Ettore Capriolo, was beaten up and stabbed in his Milan apartment. In October 1993, William Nygaard, the Norwegian publisher of The Satanic Verses, was shot three times and left for dead outside his home in Oslo. Bookshops were firebombed for stocking the novel.

Mayer himself was subject to a vicious campaign of hatred and intimidation. “I had letters delivered to me written in blood,” he remembered. “I had telephone calls in the middle of the night, saying not just that they would kill me but that they would take my daughter and smash her head against a concrete wall. Vile stuff.”

The defence of free speech: an irrevocable duty

And yet neither Mayer nor Penguin had countenanced backing down. “I told the board, ‘You have to take the long view. Any climbdown now will only encourage future terrorist attacks by individuals or groups offended for whatever reason by other books that we or any publisher might publish. If we capitulate, there will be no publishing as we know it.'” Mayer and his colleagues recognised that “what we did now affected much more than simply the fate of this one book. How we responded to the controversy over The Satanic Verses would affect the future of free inquiry, without which there would be no publishing as we knew it, but also, by extension, no civil society as we knew it. We all came to agree that all we could do, as individuals or as a company, was to uphold the principles that underlay our profession and which, since the invention of movable type, have brought it respect. We were publishers. I thought that meant something. We all did.”

Nygaard, too, was resolute in his refusal to give way. He spent weeks in hospital, followed by months of rehabilitation. It was two years before he could fully use his arms and legs again. “Journalists kept asking me, ‘Will you stop publishing The Satanic Verses?'”, he told me in an interview. “I said, ‘Absolutely not.'”

Mayer and Nygaard belonged to a world in which the defence of free speech was seen as an irrevocable duty. That world no longer exists, swept away in part by the reverberations of the Rushdie affair. In the world to which Mayer and Nygaard belonged, speech was seen as an inherent good, the fullest extension of which was a necessary condition for the elucidation of truth, the expression of moral autonomy, the maintenance of social progress and the development of other liberties. Of course, the traditional liberal defence of free speech was shot through with hypocrisy. Defenders of free expression were often wont to cite a whole host of harms –– from the incitement to hatred to threats to national security, from the promotion of blasphemy to the spread of slander – as reasons to curtail speech that they found particularly obnoxious. Yet however hypocritical liberal arguments may sometimes have seemed, and notwithstanding the fact that most free speech advocates accepted that the line had to be drawn somewhere, there was nevertheless an acknowledgement that speech was truly important and that restrictions on free speech should be the exception rather than the norm.

By the time of the Danish cartoons, free speech had come to be seen as a threat to liberty as much as its shield. By its very nature, many now argued, speech damaged basic freedoms. It was not intrinsically a good, but inherently a problem, because speech inevitably offends and harms. Speech, therefore, had to be restrained, not in exceptional circumstances but all the time and everywhere, especially in diverse societies with a variety of deeply held views and beliefs. Censorship, and self-censorship, had to become the norm.

We live in a world, so the argument ran, in which there were deep-seated conflicts between cultures embodying different values. For such diverse societies to function and to be fair, we needed to show respect for other peoples, cultures and viewpoints. Social justice required not just that individuals are treated as political equals, but also that their cultural beliefs were given equal recognition and respect. The avoidance of cultural pain has therefore come to be regarded as more important than the abstract right to freedom of expression. As the British sociologist Tariq Modood put it, ‘If people are to occupy the same political space without conflict, they mutually have to limit the extent to which they subject each other’s fundamental beliefs to criticism.’ Or, as the Muslim philosopher and spokesman for the Bradford Council of Mosques Shabbir Akhtar claimed at the height of the Rushdie affair, ‘Self-censorship is a meaningful demand in a world of varied and passionately held convictions. What Rushdie publishes about Islam is not just his business. It is everyone’s – not least every Muslim’s — business.’

Rose captures this transformation well in his description of how the meaning of tolerance has been remade. Tolerance, Rose told me, should be ‘about the ability to be exposed, and to accept things you don’t like’, the ability ‘to live with what you find distasteful. What you don’t like, what you abhor’. But the concept has, in recent years, been ‘turned on its head’. Tolerance, he explains, ‘is no longer about the ability to tolerate things for which we do not care, but more about the ability to keep quiet and refrain from saying things that others may not care to hear. Jyllands-Posten was criticised for being intolerant. That suggests that tolerance is something demanded of the one who speaks, or the one who draws the cartoon, or writes the novel, rather than something demanded of the one who listens, or looks at the cartoon or reads the novel. That’s why I say that tolerance has been turned on its head.”

Tolerance, in other words, used to mean the acceptance of diversity and difference. Today it has come to mean the very opposite: the refusal to accept diversity and difference, the insistence that others abide by my views of what is acceptable and unacceptable. Once every group insists that other groups have to respect its boundaries then every social conversation has to take place across a barbed wire fence of ‘tolerance’.

The right not to be offended

Nowhere is this trend clearer than in India. There is a long history of applying heavy-handed censorship supposedly to ease fraught relationships between different communities, a process that in recent decades has greatly intensified. Hand in hand with more oppressive censorship has come, however, not a more peaceful society but one in which the sense of a common nation has increasingly broken down into sectarian rivalries, as every group demands its right not to be offended. The confrontation over The Satanic Verses was a classic example. In 1988, the authorities caved into Islamist pressure and banned Rushdie’s novel. Not only did this embolden Muslims to continue pushing for censorship, Rose suggests, but it encouraged other groups to follow suit. Hindus, he says, ‘learnt from Muslims. Because the Indian government gave into the Muslims, the Hindus then came forward and said, “We also want to be accommodated in the same way. We want things we don’t like banned.” What it shows is that if you start to give in, there is no end to it.’

A week after I interviewed Rose, a train of events was set off that perfectly illustrated his observations. Salman Rushdie had been due to give a talk at the Jaipur Literature Festival about his Booker-winning novel Midnight’s Children, the film of which is to be released later this year. Muslim activists issued threats. Instead of standing up to the bullies, both local and state governments caved in, exerting pressure on the festival organisers to keep Rushdie away. The organisers in turn surrendered, condemning four writers, Hari Kunzru, Amitava Kumar, Jeet Thayil and Rushir Joshi, all speakers at the festival who had shown solidarity with Rushdie by reading from The Satanic Verses. It was, they insisted, ‘unnecessary provocation’ and threatened that ‘all necessary, consequential action’ would be taken against any others who followed suit. Emboldened by this show of weakness, Muslim activists pushed further still, forcing organisers to abandon subsequent plans for Rushdie to talk to the festival by video link.

Next it was the turn of Hindus. A week after Islamists kept Rushdie out of Jaipur, Hindu activists forced Pune’s Symbiosis University to cancel a screening of Jashn-e-Azadi, a new film about Kashmir, because it was ‘anti-India’, and to abandon a three-day seminar on the issue. If Muslims could suppress material they found obnoxious, the Hindu activists insisted, so could they.

And then, the following week, Sikhs picked up the baton. The American comedian Jay Leno had suggested that US Republican presidential hopeful Mitt Romney was so rich that he could hire the Golden Temple in Amritsar as his summer home. The Shiromani Gurdwara Parbandhak Committee, the so-called Sikh parliament in India, lodged a protest with the US ambassador to Delhi and called for worldwide protests against this insufferable insult. One Sikh filed a lawsuit against Leno in the American courts for ‘exposing Sikhs and their religion to hatred, contempt, ridicule and obloquy’.

“If you set up a marketplace of outrage,” as the novelist Monica Ali has vividly observed, ‘you have to expect everyone to enter it. Everyone now wants to say, “My feelings are more hurt than yours.”’ The demand that one should not give offence has created not a less conflicted world but one that has become more sectarian, fragmented and tribal.

Tolerance, in the way that Rose defines it, cannot, however, be a one-way street. If, as he insists, Muslims have to accept the right of others to blaspheme or cause offence, surely those others accept the right of Muslims (and of anyone else) to do the same? In reality, the opposite has happened. Hand in hand with the criminalising of criticism or ridicule of Islam has come the criminalising of Islamic dissent. Islamist preachers, such as Abu Hamza, whose incendiary sermons at Finsbury Park Mosque in north London were supposed to have influenced the 7/7 bombers, and Abu Izzadeen, who was filmed praising jihad as the ‘responsibility of every single Muslim’, have received long prison sentences for sermons deemed unacceptable. Most bizarre was the trial and conviction (subsequently overturned on appeal) of Samina Malik, a 23-year-old fantasist from West London who dreamed of jihad, and wrote awful poetry under the moniker of the ‘Lyrical Terrorist’, including such unforgettable lines as ‘Let us make Jihad / Move to the front line / To chop chop head of kuffar swine.’

Rose accepts that at the time he first published the cartoons he would probably have argued for the imprisonment of Hamza, Izzadeen and Malik. What the cartoon controversy taught him, however, is that Muslims have as much right to offend, to abuse his beliefs, as he has to offend theirs. He has, as he says, ‘definitely become a free speech fundamentalist’. So where would he now draw the line when it comes to freedom of expression? ‘At incitement to violence,’ Rose responds, but only ‘incitement to violence in the First Amendment sense. There needs to be a clear and present danger that violence will follow words in a quite short time frame.’

The war on terror and civil liberties

In February 2006, around 300 Muslims gathered outside the Danish Embassy in London, protesting against the cartoons. Four of the protesters were imprisoned for between four and six years for shouting slogans such as ‘Annihilate those who insult Islam,’ ‘Bomb, bomb Denmark. Bomb, bomb USA’ and ‘Europe, you will pay with your blood’. Had they committed a crime? No, says Rose. ‘There was no clear and present danger that those words would be followed up by action.’ The protesters, in other words, had been incarcerated not so much for bad acts as for bad thoughts.

The imprisoning of the radical preachers and the cartoon protesters has led to cries of “Islamophobia”. Western governments, many claim, are deliberately targeting Muslims for possessing unacceptable thoughts. Yet many of those now crying ‘foul’ are the ones who have paved the way for such actions. It is true that over the past decade the war on terror has provided a pretext to impose greater restrictions on civil liberties. It would be wrong to pin the blame for such curtailment of free expression simply on “Islamophobia”. The authorities have been able to curtail Islamic dissent by exploiting a culture of censorship that already existed, a culture created by the campaign against offensive, blasphemous and hateful speech. Western governments have seized upon the idea that it is wrong to give offence and transformed it into a weapon against radical Muslims as well as against critics of Islam. The moral of the story is that one should be careful what one wishes for. If we invite the state to define the boundaries of acceptable speech, we should not be surprised if it is not just speech to which we object that gets curtailed.

Critics of Jyllands-Posten retort that the cartoon controversy had little to do with free speech. It was simply about targeting Muslims. It is true that Jyllands-Posten is, as the critics suggest, a conservative paper, often hostile to immigration and obsessed by the threat of Islam. But that is an argument against its political stance, not against its right to publish cartoons that some may see as offensive or blasphemous. After all, it is not just those with nice liberal views who have the right to free speech; though increasingly many have come to believe that it should be.

More pertinent, perhaps, is the charge that, far from being a defender of free speech, Jyllands-Posten betrays double standards. In 2003, the newspaper had refused to publish cartoons about Jesus by the caricaturist Christoffer Zieler. “I don’t think Jyllands-Posten’s readers will enjoy the drawings,” the editor Carsten Juste wrote to Zieler. “As a matter of fact, I think they will provoke an outcry.”

Rose dismisses the charge of double standards. The drawings, he told me, had actually been rejected because they had been “of poor quality”, but the editor “had made the mistake of not telling the artist directly”, instead “rejecting his work with reference to the possible offence it might cause to the paper’s readership”. Jyllands-Posten has, he says, often published cartoons offensive to Christians and Jews, including ones by Kurt Westergaard. One Westergaard cartoon depicts Jesus on the cross with dollar signs in his eyes; another shows an undernourished Palestinian caught up in a barbed-wire fence in the shape of the Star of David. ‘We were not specifically trying to offend Muslims rather than anyone else,’ Rose insists.

A long history of hypocrisy

Whatever one thinks of this defence –– and I remain unconvinced –– there is no denying the long history of liberal hypocrisy about free speech. John Milton, whose Areopagitica, his famous 1644 “speech for the liberty of unlicenc’d printing”, is still rightly regarded as one of the great defences of free speech, opposed the extension of freedoms to Catholics. John Locke, upon whose work rests the philosophical foundations of liberalism, and whose Letter Concerning Toleration is a key text in the development of modern liberal ideas about freedom of expression and worship, similarly drew the line at extending freedom and liberties to Catholics and to atheists. “No opinions contrary to human society, or to those moral rules which are necessary to the preservation of civil society,” he insisted, “are to be tolerated.”

Many contemporary defenders of free speech would similarly draw the line at Muslims, often for many of the same reasons. From Geert Wilders’ campaign to outlaw the Quran, to Ayaan Hirsi Ali’s support for the Swiss ban on the building of minarets, to Martin Amis’s “thought experiment” on how “the Muslim community will have to suffer until it gets its house in order”, hypocrisy and double standards are rife in contemporary debates about freedom and liberties. Such double standards can, of course, work both ways. While some are reluctant to extend basic freedoms to Muslims, or hold Muslims to standards not demanded of non-Muslims, others on the contrary are happy to criticise or ridicule Christianity or conservatism or communism in a way that they would not dream of doing to Islam.

Many contemporary defenders of free speech would similarly draw the line at Muslims, often for many of the same reasons. From Geert Wilders’ campaign to outlaw the Quran, to Ayaan Hirsi Ali’s support for the Swiss ban on the building of minarets, to Martin Amis’s “thought experiment” on how “the Muslim community will have to suffer until it gets its house in order”, hypocrisy and double standards are rife in contemporary debates about freedom and liberties. Such double standards can, of course, work both ways. While some are reluctant to extend basic freedoms to Muslims, or hold Muslims to standards not demanded of non-Muslims, others on the contrary are happy to criticise or ridicule Christianity or conservatism or communism in a way that they would not dream of doing to Islam.

Double standards need to be confronted, not by extending restrictions but by extending speech, by ensuring not that everyone is equally deprived of liberties but that all are equally sheltered by them. To see how we should deal with double standards today, we only have to ask ourselves how we should have responded in the age of Milton and Locke. Should we have suggested that the best way to deal with their anti-Catholic bigotry was to extend to everyone the restrictions that Milton and Locke wished imposed on Catholics? Or should we have argued that restrictions on Catholics were wrong and that all deserved liberty? With four centuries worth of hindsight the answer to most people is crystal clear. It should be equally so today, in response to free speech and the hypocrisy of anti-Muslim prejudices.

Prejudice reveals itself not simply in double standards but also in a distorted image of the “Other”. In the case of Jyllands-Posten, the newspaper used the publication of the cartoons to play upon tawdry stereotypes of Muslims, helping promote the idea that the views of radical Islamists represented that of all Muslims.

The publication of the cartoons caused no immediate reaction, even in Denmark. Only when journalists, disappointed by the lack of controversy, contacted a number of imams for their response did Islamists begin to recognise the opportunity provided not just by the caricatures themselves but also by the sensitivity of Danish society to their publication.

Among the first contacted was the controversial cleric Ahmed Abu Laban, infamous for his support for Osama bin Laden and the 9/11 attacks. He seized upon the cartoons to transform himself into a spokesman for Denmark’s Muslims. His Islamic Society of Denmark was closely linked to the Muslim Brotherhood but had little support among Danish Muslims. Danish Muslims, as the sociologist Jytte Klausen points out, ‘are for the most part politically placid and disinclined to support Islamic radicals and extremists’. But, observes Klausen in The Cartoons that Shook the World, her academic study of the controversy, Jyllands-Posten’s “attack on the ‘mad mullahs’ stereotyped all Danish Muslims as radical extremists”.

Rose acknowledges that this was exactly what happened. “I think it was a mistake,” he says, “a mistake not just made by Jyllands-Posten but a mistake broadly being made by the media, that every time you wanted to hear a Muslim voice, you went to one of these radical imams. That reinforced that sense of us versus them.”

The idea of a “clash of civilisations” between Islam and the West, an idea first popularised by the American political scientist Samuel Huntington a decade before 9/11, has for many come to define the following decade. But it is not just conservatives, or those hostile to Islam, who have come to see the world in this way. Many of the fiercest critics of the “clash of civilisations” thesis, many of Jyllands-Posten’s harshest opponents, have themselves helped promote the idea of a world divided into irreconcilable cultures.

There were many Danish Muslims who were happy to see the publication of the cartoons. Bunyamin Simsek was a councillor in the city of Aarhus. He was religious –– he attends mosque, does not drink or eat pork and fasts at Ramadan. But he was also secular. “There is,” he insisted, “a large group of Muslims in this city who want to live in a secular society and adhere to the principle that religion is an issue between them and God and not something that should involve society.” Appalled by the way that Raed Hlayhel and Ahmed Abu Laban had come to be seen as the authentic spokesmen for Muslim concerns, Simsek set up a network of Muslims opposed to the Islamists and helped organise a counter demonstration to the cartoon protests. “We wanted to show that not all Danish Muslims are Islamists,” he said. “In fact very few are. But it is the Islamists like Raed Hlayhel and Abu Laban who get all the hearing.”

Voices such as Simsek’s were rarely heard in the media because they did not fit into the narrative of what constituted a Muslim, a narrative promoted by liberals as well as conservatives, by those sympathetic to Islam as well as those hostile to the faith. The Danish MP Nasser Khader, like Simsek a critic of the campaign against the cartoons, tells of a conversation with Toger Seidenfaden, editor of Politiken, a left-wing newspaper highly critical of Jyllands-Posten and of the publication of the cartoons. ‘He said to me that the cartoons insulted all Muslims,’ Khader recalled. ‘I said I was not insulted. He said, “But you’re not a real Muslim.”’

For left and right, for liberal and conservative, to be a proper Muslim was to be offended by the cartoons. Once Muslim authenticity is so defined, then only a figure such as Abu Laban can be seen as a true Muslim voice. Bunyamin Simsek and Nasser Khader – and Salman Rushdie – came to be regarded as too westernised, secular or progressive to be truly of their community. Because only one side of the conversation is regarded as ‘authentic’, what is often in reality a debate within the community which comes to be seen as offensive to the community itself. This is not just true of Muslims. The Sikh protesters who forced Gurpreet Kaur Bhatti’s play Behzti offstage in 2004, a year before the cartoons were published, were seen as more authentically Sikh than Kaur Bhatti herself. And so have Jewish, Christian, Hindu and a host of other protesters who have in recent years cried ‘Offence!’ about films, plays, novels or art that they have disliked.

For left and right, for liberal and conservative, to be a proper Muslim was to be offended by the cartoons. Once Muslim authenticity is so defined, then only a figure such as Abu Laban can be seen as a true Muslim voice. Bunyamin Simsek and Nasser Khader – and Salman Rushdie – came to be regarded as too westernised, secular or progressive to be truly of their community. Because only one side of the conversation is regarded as ‘authentic’, what is often in reality a debate within the community which comes to be seen as offensive to the community itself. This is not just true of Muslims. The Sikh protesters who forced Gurpreet Kaur Bhatti’s play Behzti offstage in 2004, a year before the cartoons were published, were seen as more authentically Sikh than Kaur Bhatti herself. And so have Jewish, Christian, Hindu and a host of other protesters who have in recent years cried ‘Offence!’ about films, plays, novels or art that they have disliked.

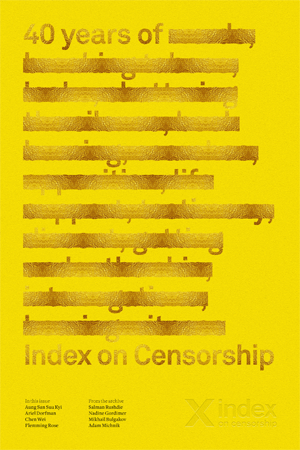

Both sides in this debate about Islam have hijacked the issue of free speech, bending and distorting the concept of liberty until it has become almost meaningless. On one side are those who ostensibly defend free speech, but do so only in tribal terms, as a weapon to be wielded by the West against Islam, a means of depriving Muslims of basic liberties. On the other, are those who ostensibly defend liberties, and Muslims, but only by constraining free speech, incarcerating the very means by which we are able to think and debate and argue, and be human. Both sides are, in their different ways, enemies of free speech, of liberty, of our essential humanness. Seven years on from the cartoon crisis, two decades after the Rushdie affair, 40 years after the founding of Index on Censorship, our task today is not just to defend free speech but to liberate it from the shackles of bad faith.

Kenan Malik is the author of From Fatwa to Jihad (Atlantic) and a prolific commentator, broadcaster and writer.