Could greater control over Bollywood help reverse a culture of female objectification in India? No, argues Mahima Kaul, but the roles of women in Bollywood films could still do with a makeover

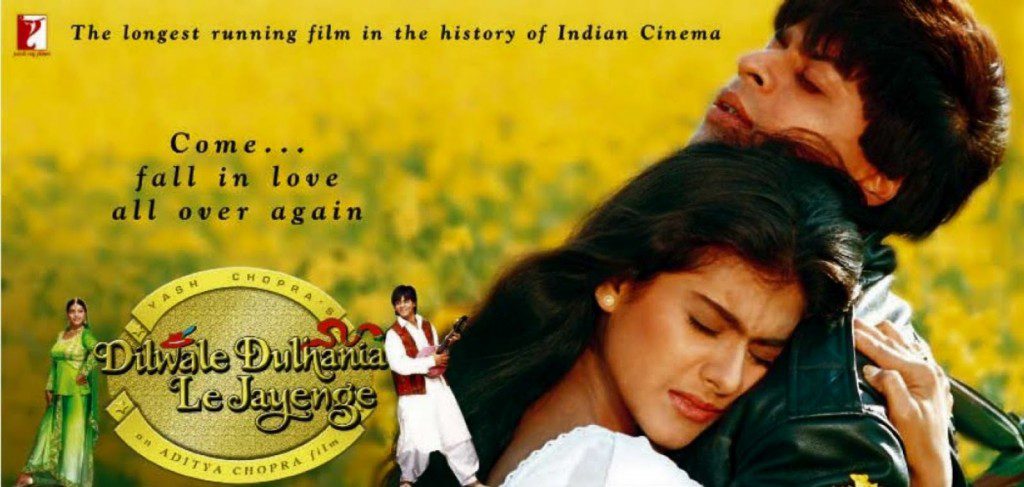

In 1995, a movie called Dilwale Dulhaniya Le Jayenge swept India. It became an instant classic and cult hit. The short synopsis of the movie is that Simran, an Indian girl who grew up in the UK under a very strict father has been promised as a bride to a young man in India. Raj, the boy she fell in love with during a road trip in Europe follows her to this small town in India where wedding preparation is underway, and wins her family over. The movie, while comedic and heartwarming, also revealed the tougher side of Indian society. Simran did what she was told, as did her mother. In the end Simran gets to be with Raj, but not until Raj has taken permission from her father to marry her. While shining a light on the patriarchal nature of Indian society, in the end, the love story is resolved through a negotiation between the two men. I was 12 years old when it was released.

There have been many movies in Bollywood since then. Some figures estimate there are about 1,500 movies released in Bollywood annually. They are filled with raunchy songs, “item” numbers — a gratuitous song which features a scantily-clad woman often dancing for the pleasure of a room full of men — and very minor decorative roles from the ‘heroine’. The hero often harasses the heroine, who is somehow charmed by his behaviour and falls madly in love with him. The portrayal of women in Bollywood, and their larger effect on Indian society has been called into question following the brutal gang rape of a young girl in the capital, New Delhi. Many argue that Indian popular culture is full of misogyny, and Bollywood too needs to own up to its role in fuelling this culture. As Ritupurna Chatterjee writes, “it will be highly presumptuous to assume that Hindi cinema is the root cause of a spike in sexual assaults. But Bollywood and regional cinema in equal parts, because of their reach, scope and influence, have a larger role to play in assuming responsibility for the message it sends out to millions of audience — some highly impressionable.” India’s population has now exceeded 1.2 billion, and even though literacy has increased quickly in the past years, a little over 25 per cent of the country’s population is still illiterate.

Is it fair to blame Bollywood, or even expect it to produce movies that adhere to a higher standard? As Bollywood mega star and bad boy Salman Khan argued in an interview — each movie has a good guy and a bad guy. It isn’t Bollywood’s fault that people choose to follow the villain. The superstar also added that if not the death penalty, rapists should be sentenced to life. Others, like director Anurag Kashyap, agree with the general sentiment that Bollywood, being such a huge influence for Indian society, has a responsibility to produce movies that show women in progressive light, but hold that censorship is not a viable way to achieve this goal, tweeting that moralising censorship would create “another kind of Taliban”.

By the time I was 18, a movie called Dil Chahta Hai exploded onto the scene and instantly became a cult classic. It is a story of three boys, Akash, Sameer and Siddharth, who have a last road trip to Goa before their “adult” lives begin. Fancy cars, beaches, no parental supervision and even a romance with an American girl made every Indian teenager want to go to Goa instantly. The second half of the movie sees the boys struggling with ‘adult’ issues. Unsurprisingly, one of the plots revolves around Akash needing to crash a wedding to convince his love interest not to go ahead with an arranged marriage, while his friend falls in love with a divorcee who dies in the course of the movie. While the stories bring up different aspects of Indian society, and how women are victims to its ways, they are mainly served up as plot devices to show how the boys grow into men.

One of the biggest blockbusters of 2009 — I was 26 then — was a movie called 3 Idiots. It dealt with the intense premium Indian parents and education institutions put on rote learning as opposed to creativity. The formula, using three boys to tell the story of education in India, again used women only as accessories in the story.

The larger point being made here is that even when a female movie character’s role is more than decorative, the heavy emphasis on men’s problems make it appear as though it is the Indian man who is complex with real problems and the woman only serves as a support system. Movies have found new cities, settings and even broader societal issues to tackle, yet, seem to be in a state of arrested development when it comes to the power dynamic in gender relationships. There are a few movies that have broken the mould and present women as strong independent characters. Women with not only professional lives and the confidence to stand up to a man, but also the independence to make a decision for herself and not be punished for it in the course of the movie.

Bollywood is correct that it is free to express what it wants, and tell the stories it wants. They have rejected censorship as a tool to “elevate” the kind of content they generate. Some writers have argued that only blaming the producers of pop culture is dangerous, and that the audience needs to introspect as well — Shougat Dasgupta pleads with audiences to “question the invariably sexist, xenophobic, homophobic, plain stupid assumptions of the pop culture we consume”.

It is interesting then that many were shocked by the message sent by one of 2012’s most highly anticipated movies, Cocktail, the story of three young people sharing a flat in London. Ditching his club hopping, alcohol drinking girlfriend, the leading man, a womanizer, falls in love with the god fearing docile “good” girl. What happens? His former paramour, played by leading actress Deepika Padukone, then ditches her short skirts for salwar kameezes and the neighbourhood bar for the kitchen to win him back. If this doesn’t send the wrong signal about female empowerment, then what does?

Mahima Kaul is a New Delhi based journalist. She tweets from @misskaul.