Free speech is enshrined in Brazil’s constitution. But in reality, those with power and influence can stifle critical debate and reporting. It’s time to overhaul the system, says Rafael Spuldar

Brazil’s constitution guarantees both freedom of the press and free speech. The government does not impose censorship in the media. However, recent actions taken by the judiciary — most of them concerning the removal of online content deemed defamatory — have been extremely controversial.

In September 2012, a judge from the state of Mato Grosso do Sul ordered the arrest of Fabio Coelho, Google’s top executive in Brazil, after videos about a mayoral candidate were uploaded to YouTube. They were considered to be offensive to Alcides Bernal, who was running for office in the state’s capital city. When the posts were not immediately deleted, Brazil’s federal police temporarily detained Coelho.

Fabio Coelho’s case illustrates clearly how rigid the country’s laws are when it comes to offensive material. Still, many people argue that some of the judges’ decisions in these cases have been excessive. “There are gaps in Brazil’s electoral legislation that make this kind of situation possible”, said Google Brazil’s Public Policy Senior Counsel Marcel Leonardi when asked about Coelho’s detention. He hopes that the case will shine a light ‘on the need to adjust Brazil’s law, so that legitimate political outcries from internet users can be differentiated from, say, unlawful propaganda. The internet’s dynamics need to be understood.”

By not removing the videos, Google tried to make a case for the need for more liberal laws regarding free speech in Brazil, says Marcelo Träsel, Digital Journalism Professor at Pontifícia Universidade do Rio Grande do Sul University (PUCRS) in Porto Alegre. To make the internet giant responsible for the content “is like making builders liable for crimes committed by apartment-buyers, or a bus company for crimes committed by its passengers”, he says. “As long as Google has proper means for filing complaints about content — and it does have them — and takes effective measures to restrict abuses when warned about them, the final responsibility must be laid upon the client that published controversial material”, he adds.

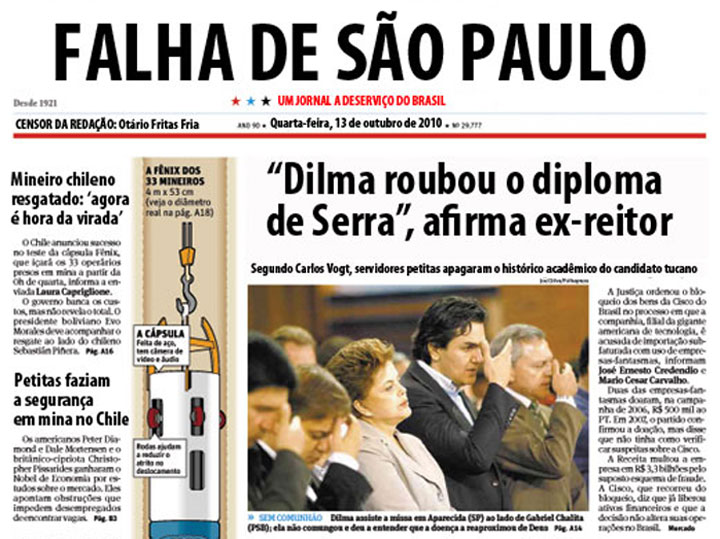

When Folha de S Paulo, the country’s most influential daily newspaper, was criticised for its coverage of that year’s general elections in a blog called Falha de S Paulo (Folha, meaning “newspaper”, was replaced with falha, meaning “fail”), Folha filed a lawsuit claiming the blog’s logo, content, pictures and text font imitated its graphic design and confused web users. A judge demanded the website be removed and imposed a daily fine on its authors. On 20 February, the ban was upheld. “Censorship is supposed to be prohibited [in Brazil]”, said one of the blog’s creators, Lino Ito Bocchini, in an interview with the website Comunique- Se, “but in reality, free speech is only guaranteed to those who have money”. He later expressed his intention to appeal the decision. The case was raised with Frank la Rue, UN Special Rapporteur on Freedom of Opinion and Expression. In a recent visit to Brazil, he referred to the situation as “terrible”. Marcelo Träsel agrees that financial pressure comes into play in cases like this. “Politicians, business people and other powerful personalities found that they can silence their critics by filing lawsuits. Influential figures who become the subject of a scandal are in a financial position to “torment” those who criticise them. “These people don’t even need to win in court”, Träsel says. Filing a lawsuit claiming damages could be enough to shut up a whistleblowing blogger, for example. “I believe that’s the main threat to free speech in Brazil, and I believe that cases like Falha de S Paulo will grow in number.”

The practice of filing lawsuits to remove defamatory content from the internet also disturbs Google’s Marcel Leonardi. “The internet gives you the possibility to immediately respond to anyone, and in many different ways, like posting videos or creating hyperlinks,” he told Index. In situations like the Falha de S Paulo case, the best way of replying to criticism is by having an online presence so that people can “inform and reply to critics in one’s own virtual space,” he said. According to a recent Transparency Report published by Google, Brazil tops the list of countries that regularly removed digital content. In Leonardi’s opinion, Brazil will continue in this vein unless the “culture of lawsuits” is somehow overcome.

In Brazil, the judiciary has the exclusive power to order content to be taken down from a website — no government body has the right to do so. Other public agents, like federal prosecutors, can only file their demands through lawsuits, as regular attorneys must do. Leonardi believes Brazil is caught between liberal countries like the US, which seldom accepts non-copyright related content removal, and less democratic nations where the main problem isn’t content removal but attacks against publishers and direct government censorship over websites and social media.

Experts like PUCRS’s Marcelo Träsel say that adopting laws that differentiate the “virtual world” from traditional media would bring more clarity to judges’ decisions. In 2012, Congress debated two initiatives that pointed in this direction. One of them — a bill that deals with digital crimes, specifying correlated penalties — was voted in by lawmakers in early November.But another draft bill — called Marco Civil da Internet, or the Internet Civil Right Framework, seen as an “Internet Bill of Rights” — was shelved in November. Marco Civil would have guaranteed basic rights for users, content creators and online intermediaries and established that providers are not responsible for user content. It also would have guaranteed net neutrality, a move that angered the telecommunications industry, as it would prevent them from charging different rates for the various kinds of online content.

Deputy Alessandro Molon, who sponsored the bill, says Brazil’s main telecom companies lobbied hard against it, arguing it was contrary to the principles of the free market. “Approving Marco Civil would be a very important step to guarantee freedom of expression in Brazil”, notes Träsel. However, this type of guarantee for civil rights is unlikely to be seen in the country for the foreseeable future, and judges’ decisions are likely to remain as controversial and damaging as ever.

Rafael Spuldar is Index’s regional editor in Brazil. He tweets from @spuldar