Index on Censorship views press freedom as one core part of the fundamental right to freedom of expression.

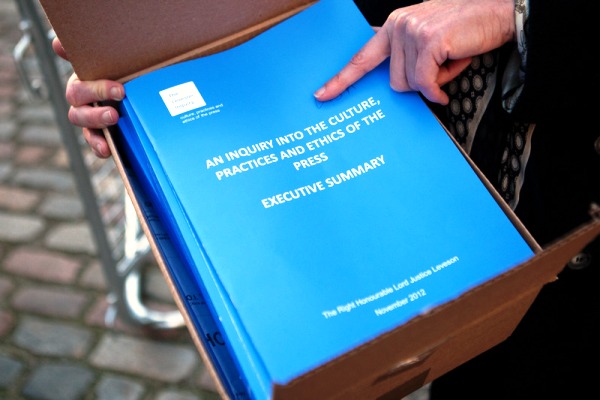

Index engaged constructively with the Leveson Inquiry, submitting written and oral evidence.

Index has called consistently for a tougher, new independent press regulator that can tackle standards as well as complaints. Such a regulator must be voluntary.

Political Involvement in Regulation Crosses a Red Line for Press Freedom

Following the publication of the Leveson Report, the Royal Charter, accompanied by various statutes, was agreed through a process of cross-party negotiation (often behind closed doors). Index is highly concerned at the politicisation of the process of establishing a new press regulator. Index is opposed to politicians determining the characteristics of a press regulator, and to any form of press statute, or statutory underpinning of a press regulator.

One of the vital roles of a free press in a democracy is to hold politicians, government and powerful individuals and organisations to account. As the Leveson Inquiry itself showed, politicians have a strong self-interest in securing favourable press coverage as one part of a route to securing public support and so political power. A free press must be just that — free from political interference, including from politicians voting on the establishment of, and characteristics of, a press regulator. The press is subject to the same laws as other individuals and organisations, and should not have to work under specific press laws in a democracy.

The Royal Charter, and its statutory underpinning, represents a dangerous moment for press freedom and freedom of expression in the UK. The damage will spread wider than just the UK – the example parliament is setting has already been noted by a range of regimes around the world, and many journalists have expressed concern at the impact it will have on the political controls they may come to face in their own countries.

The Royal Charter itself is not a statute but it is drafted and approved by the Privy Council, which includes ministers and politicians. This in itself represents an unacceptable political involvement in the establishment of a supposedly independent press regulator.

Statutory Underpinning

The provisions of the Royal Charter are underpinned by new clauses introduced into various Bills going through parliament. This statutory underpinning means that MPs — and Lords — are in control of the establishment and characteristics of a press regulator, including the incentives and disincentives for joining the regulator. Politicians in a democracy should not vote on and make specific laws for the press – it undermines the principle of press freedom and threatens the role of the press in holding those politicians to account.

Changing the Royal Charter

One of the new statutes, an amendment to the Enterprise and Regulatory Reform Bill, determines that in future any Royal Charter can only be changed with a two-thirds vote in both houses of parliament. Through this statute, politicians may vote now and in future on the characteristics of press regulation. As the cross-party consensus on the Royal Charter shows getting to such a two-thirds majority may not be difficult. And a simple majority vote could, anyway, cancel this statute.

Exemplary damages

A further statutory clause, in the Crime and Courts Bill sets out that an organisation which does not join the regulator but falls under its remit will potentially become subject to exemplary damages should they end up in court. In addition, even if they win, they could also be forced to pay the costs of their opponents.

Index is opposed to the imposition of exemplary damages which is likely to have a strongly chilling effect on freedom of expression. It is also quite possible that this measure would be rejected in the European Court of Human Rights.

Supporters of the royal charter say that exemplary damages would only apply to “reckless” action by journalists, but it is likely that a court would find that a breach of Article 8 rights to privacy and reputation is by definition “reckless”.

Arbitration

Index on Censorship supports a voluntary mediation system that would allow swift and inexpensive resolution of disputes based on mutual consent between complainant and defendant. The arbitration arm of the regulator established in the Royal Charter does not fulfil this role. It is not universally accessible and parties may be punished through costs and damages if they refuse to take part. This could contravene the right to legal access under article 6 of the European Convention on Human Rights.

Directing corrections

A tougher new independent regulator could reasonably require corrections to be made. The Royal Charter goes beyond this and proposes the regulator will be able to “direct” the wording and placement of apologies and corrections. Index opposes this effective transfer of editorial control. It represents a level of external interference with editorial procedures that would undermine editorial independence and undermine press freedom.

Scope

The Royal Charter is designed, in its own words, to regulate “relevant” publishers of “news-related material”. It sets out a very broad definition of news publishers and of what news is (including in the definition celebrity gossip). Many organisations who publish “news” specific to their fields may be caught in the regulator’s wide net.

Despite some subsequent attempts by politicians to establish some exclusions, such as for trade publications and charities for instance, the attempt to distinguish press from other organisations remains deeply problematic.

The Royal Charter aims to apply to news on the internet in a sweeping manner (something Leveson paid little attention to and that received very little comment in his report). As concern has spread over the potential inclusion of even small scale blogs, the government has started to look at ways to widen exempted categories.

Index is highly concerned at the rapid, sweeping and ill-considered move to regulate a major part of the internet — including in that news outlets located in other countries but focused onto the UK market (however defined).

As concern has spread over the potential inclusion of even “small scale” blogs, the Department of Culture, Media and Sport has started to look at ways to widen exempted categories.

Even defining “small-scale” is problematic in an age when individual blog posts can go “viral” and gain thousands of readers in a short period. Meanwhile, the role and practices of traditional publishers and blogs are converging rapidly, making it entirely likely that the proposed system will be mired in confusion from the very beginning.

Attempting to limit the impact of an ill-thought out, misconceived Charter and statutes on many internet users risks creating confusion and a chilling effect on freedom of expression, and could still affect many unintended targets — as well as setting a very bad example internationally at a time when the UK government repeatedly states it is promoting digital freedom internationally.