The media’s infatuation with a single narrative is drowning out the country’s diversity, giving way to sensationalist reporting and “paid for” news. But, says Bharat Bhushan, moves towards regulation could have a chilling effect too

India’s growing global importance and ambitions have had a detrimental impact on free speech, creating a discourse that drowns out diversity in the media. Its “big power discourse” has been shaped primarily by two processes — economic liberalisation, which began in 1991, and the nuclearisation of India, in particular the five nuclear tests India conducted in 1998. The former has propelled the country, along with China and East Asian countries, into the role of a future growth engine of the world economy. And the latter has fed its aspiration to be recognised as a legitimate nuclear power.

The Indian media was initially critical of the attempts by international financial institutions to prise open the Indian market. However, it quickly fell in line as media owners realised that they stood to gain directly from economic liberalisation and the new class of consumers it created. If readers with disposable incomes increased, so would advertising revenue. This led to an increasingly insular focus on the emerging middle class, which represents less than 25 per cent of India’s population.

As it became an active partner in promoting a consensus on economic liberalisation, the media shaped the image of a new middle class as atomised and individualistic consumers united only by their disdain for state intervention and their aspirations towards international patterns of consumerism. New restaurants with international cuisine — often with chefs imported from abroad – serviced them, as did international fashion outlets, fast-food chains and giant malls for a world class shopping experience. The schools their children attended had the epithet “international” in their names, and school trips metamorphosed into travel to foreign destinations. The media helped to invent this “aspirational” middle class and to shape it ideologically. Editors of big newspapers prided themselves on their ability to double as food writers and experts on matching Indian curries with this or that wine, or on being experts on fashion, lifestyle and popular music. Newspapers and television channels introduced special sections and programmes to bring the world in all its consumerist glory to the Indian living room.

Increasingly, the middle class was seen as a homogeneous group of consumers with one voice and one set of values, a ripe constituency for buying into the “big power” dream.

Re-imagining India

At the same time, the collapse of the Soviet Union and the end of the Cold War made the Non-Aligned Movement, which had sought to represent the interests of developing countries during that period, in many ways irrelevant. So India began its search for a seat at the international high table. The nuclear tests of 1998 followed and the subsequent US attempts to create a halfway house for India as a nuclear power outside the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty boosted India’s aspirations.

Internationally, the size of the Indian market, the shifting of international economic growth engines to the East, and India’s own growth story helped re-invent the country as a potential world power. The “big power” discourse has been fuelled by the creation of new blocs of emerging economies like the BRICS (Brazil, Russia, India, China, South Africa) and IBSA (India, Brazil, South Africa); by India’s G20 membership to its forging of a new strategic partnership with the US; and by US talk of and plans for strategic rebalancing of US interests in Asia.

FROM INDEX ON CENSORSHIP MAGAZINE

Global view: Who has freedom of expression? | The multipolar challenge to free expression | Censorship: The problem child of Burma’s dictatorship

This article appears in the current issue of Index on Censorship, available now. For subscription options and to download the app for your iPhone/iPad, click here.

The impact on the media has been all too apparent. Firstly, it has wholeheartedly adopted an agenda that puts primacy on sitting at the international high table over tackling internal inequities. Secondly, the re-invention and re-imagining of India has largely been taken over by strategic affairs experts and diplomats — to the detriment of other voices and other national priorities. They get a disproportionate space in the media as compared to those working with the issues of the poor, migrants, displaced people and other socially and politically marginalised groups.

The media has also pandered to nationalist sentiment, which has been used to curtail the activities of civil society and silence critical voices. These groups are regularly accused of sedition, anti-national activities and undermining the unity and integrity of the Indian union. By perpetuating the “big power” discourse, the media has helped create a feeling of belligerence towards India’s neighbours, often adopting more hardline positions than the government and egging it on to demonstrate its might when it comes to relations with countries in the region, particularly Pakistan, China and the Maldives.

This rhetoric drives opposition politicians and the wider public discourse towards jingoism. Those who have no stake in this “big power” discourse and feel left out of the policies that emanate from it are pushed away from mainstream political parties and towards insular political groupings and organisations.

As more of the country’s citizens become literate and witness an increase in their disposable incomes, the media explosion in India continues unabated. Internationally, newspaper readership is on the decline, but in India it continues to grow and is expected to continue doing so for some time. There are more than 2,000 daily newspapers in the country, and it is estimated that for each percent of growth in literacy (currently at 74% of the population), newspaper readership increases by five million readers.

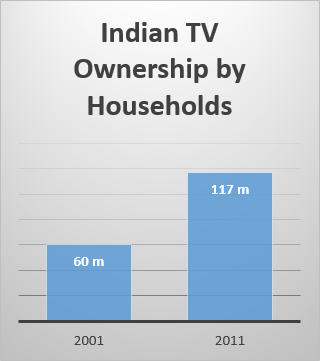

In 2001 there were only 60 million TV-owning households in India. That number had gone up to 117 million by 2011. And the number of TV channels grew from nine in 2000 to 122 in 2010 – and to 825 by December 2011.

However, the competition and market expansion have not led to an improvement in quality or diversity. In fact, every TV channel and newspaper looks like a clone of the next.

Irresponsible reporting and ‘paid-for’ news

The media has often made serious errors while reporting on terrorist acts, declaring arrested Muslim suspects as the perpetrators of crimes even before their trials have begun, publishing their names and branding them as terrorists prematurely. And when the media has been proven wrong, it has not taken corrective action.

There are a number of examples of the broadcast media behaving in an irresponsible manner, with television programmes displaying visuals that could be described as insensitive to certain groups of people, sensationalising news, invading people’s privacy, slandering public figures and wilfully misrepresenting news. Some news programmes seem to take covert pleasure in depicting violence against women, while at the same time sounding indignant about it: in December 2012, one channel broadcast a multi-media message that depicted the gang-rape of a woman even as it denounced the crime.

The news-for-cash or ‘paid-news’ controversy in 2009, when it was exposed that various newspapers had sold news space to politicians, exemplified the falling standards of journalism in the country. Major newspapers have entered into lucrative partnerships – such as equity for coverage deals called ‘private treaty partnerships’ – with the corporate world. The reader no longer knows where advertising and public relations end and news begins.

A call for regulation

Media observers, the chairman of the Press Council of India, the judiciary and some politicians have suggested that the quick fix for this malaise is some kind of regulation.

Media observers, the chairman of the Press Council of India, the judiciary and some politicians have suggested that the quick fix for this malaise is some kind of regulation.

Media stakeholders have disparate views on this question. The government plans to introduce regulation to heel rabid and irresponsible sections of the media, some of which have been exposed in recent years as being corrupt or open to corruption. Media owners want to ward off state intervention by introducing some form of self-regulation.

Journalists are divided on the issue: some support government regulation with or without punitive measures and invite monitoring, while others favour self-regulation.

The state has made several attempts to regulate the media, some of them rooted in existing law and others part of an evolving dynamic. The current chairman of the Press Council of India (PCI), retired Justice Markandey Katju, began demanding punitive powers to regulate the media the moment he took over in October 2011. He approaches the role equipped with a self-righteous notion of what media priorities ought to be and crusades with reformist zeal to introduce punishment for misdemeanours.

Katju’s argument for regulation comes from Article 19(2) of the Indian constitution, which allows for ‘reasonable restrictions’ on free speech, otherwise guaranteed by Article 19. ‘Reasonable restrictions’ can be imposed on freedom of expression in the interests of the security of the state, friendly relations with foreign states, public order, or decency and morality; for contempt of court, defamation or incitement to an offence; and to protect the sovereignty and integrity of India.

Katju also wants television to come under the ambit of the Press Council of India (PCI). He has been roundly criticised by various media bodies for seeking punitive powers – currently, the PCI only has the power to warn, admonish and censure. Its effectiveness depends on the level of co-operation it can solicit from media practitioners as well as media owners – all of whom are represented on the Council.

The unpopularity of Katju’s recommendations within the media stands in stark contrast to the support he has received from the general public. There are many who think that he is talking sense – that with a free media must come a sense of responsibility; if it is absent, then responsibility must be enforced with a stick. The public anger towards the erosion of high standards and values in the media is all too palpable.

A young member of parliament from the ruling Congress Party, Meenakshi Natarajan, was so moved by Katju’s suggestions that she even tried to introduce the Print and Electronic Media Standards and Regulation Bill 2012 to parliament. It proposed the setting up of a media-regulating authority which would have sweeping powers to impose fines, suspend licences and ‘ban’ or ‘suspend’ coverage of an event or incident that ‘may pose a threat to national security from foreign and internal sources’. The MP’s own party eventually disowned the bill, however, and it was never introduced.

Online restrictions

India’s telecom minister Kapil Sibal also took steps to regulate the media. In April 2011, he called a meeting with representatives from Google, Facebook, YouTube and Yahoo!, among others, to suggest that they ‘prescreen’ online content. Although the government has been fairly successful in ordering hate speech and defamatory content to be removed from some of these sites, there is no law that allows for a pre-publication crackdown.

(Read Pranesh Prakash’s full account of the obstacles to online freedom in India in Index on Censorship , ‘Digital Frontiers’, published in December 2012.)

After a huge outcry from users across social networking sites, the government has been sending in its requests directly to companies like Google, which then makes a decision on whether to remove objectionable content. In 2011, Google disclosed that it had received 358 ‘takedown’ requests from the government between January and June 2011 and that it acted on the request in 255 of the cases. This disclosure came after a Delhi court issued an ex parte order to 22 websites, including social networking platforms, to remove anti-social and antireligious content – photographs, text, and videos that might hurt religious sentiments.

But, interestingly, Google claimed that most of the items removed related to criticism of the government. In 2012, the government issued a set of guidelines for online behaviour, aimed not only at websites and internet companies like Facebook and Google, but also at ‘intermediaries’ like internet service providers, cybercafes, blogs and search engines.

Many believe that these guidelines are so arbitrarily defined that some of them are either unconstitutional or impractical or both. Intermediaries are asked to remove content that is vaguely defined as ‘hateful’, ‘harassing’, ‘blasphemous’ and ‘disparaging’.

Advocates argue that this might violate the Indian constitution’s guarantee of freedom of expression. The government is not short of legal mechanisms to deal with the media. The constitution itself has five articles that relate to media reporting. There are 31 press laws and acts in India promulgated by the states and the Union government. In addition, the Indian Penal Code has 18 sections that have a bearing on media reportage, and there are another 18 sections relating to the media in the Criminal Procedure Code. There are also programme and advertisement codes for television content, which have been issued under the Cable Television Networks (Regulation) Act 1995, and some internet content standards have been provided under the Information Technology Act of 2000.

Internet users became aware of the dangers of the now notorious Section 66A of the Information Technology Act, which punishes the sharing of offensive internet content, when a cartoonist was arrested in September 2012 for posting ‘objectionable content’ on his website. A month later, an industrialist from Puducherry (formerly Pondicherry) was arrested under Section 66A for posting a tweet against the Indian home minister’s son. In November 2012, two young girls were arrested in Maharashtra under the same law – one for complaining on Facebook against the complete shutdown of cities in the state after the death of Hindu right-wing leader and father of hate speech in India, Bal Thackeray, and the other for ‘liking’ her comment.

The provisions of Section 66A are now being challenged in two high courts as well as the Supreme Court. Meanwhile, the government was forced under public pressure to introduce new guidelines, making arrests under this section of the IT Act subject to clearance by officers at the level of deputy commissioner of police in cities and inspector general of police in rural areas, rather than by local constables. However, web activists are concerned that these guidelines may not be legally binding.

India’s judiciary also poses a threat to free speech. In recent years, it has taken three major initiatives to regulate the media. In 2012, the Supreme Court of India pronounced the ‘doctrine of postponement of publication’ of hearings. Its ostensible purpose is to prevent immediate and sensational reporting on court proceedings that may prejudice the trial. However, the Supreme Court stopped short of framing any guidelines.

A second initiative was taken in January 2013, when a lower court banned the media from covering the trial involving the December 2012 gang-rape that triggered demonstrations across the length and breadth of India. The Delhi High Court later lifted the ban in the face of an appeal.

Then, in April 2013, the Delhi High Court ruled that the absence of state intervention on its behalf did not guarantee a rich and diverse media environment and argued for a statutory broadcast regulatory body. The court said that such a body was required to ensure that media organisations complied with the provisions of the Cable Networks (Regulation) Act 1995 and the Cable Television Networks Rules 1994.

The legislature also tries to curtail free speech through the Law of Parliamentary Privileges and through the Speaker’s power to censor the press. Because of these powers, the media has been unable to publish or report on remarks by legislators expunged by the presiding officer of parliament; TV cameras covering live proceedings of the legislature have been switched off under orders from the presiding officer. These laws need to be challenged in a court of law because, prima facie, they seem to be unconstitutional.

The law of criminal defamation, which has been used to harass journalists, also needs a rethink.

Whichever way one looks at it, protecting free speech while regulating the media remains a challenge. But, at the same time, India’s media is becoming increasingly monochromatic.

©Bharat Bhushan

Bharat Bhushan is an independent journalist based in New Delhi and former editor of the Mail Today. Contact him on [email protected]