As emerging markets command influence on the international stage, Saul Estrin and Kirsty Hughes look at the impact on economics, politics and human rights

The emergence of a multipolar world is opening up a range of economic, political and human rights debates about the changing world order. The growing economic and political weight of China in particular, but also of countries like Brazil, India, South Africa and Turkey, is transforming the familiar post-war geopolitical and geo-economic order that, even after the events of 1989 or 9/11, seemed in many ways quite familiar, despite the demise of the Soviet Union.

After decades of US hegemony and great significance in world affairs for the larger European powers, new actors seem to crowd the field as the old giants gently decline. How much is really changing and how fast? China has grown very rapidly as an economy, but remains underdeveloped in many regions. India, Brazil and Russia are also some way from overtaking the United States, European or Japanese economies in terms of size and are even further behind in productivity terms. Yet with the trend to a multipolar world being strongly reinforced by the economic crisis of the last few years, focused as it has been on the EU and US, many of the emerging powers have anincreasing voice in global political and policy discussions. From the new role of the G20 since 2008 to the new summit encounters of the BRICS (Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa), there is a growing realisation that global conversations, whether they be about economic policy or human rights, have a wider range of strong and powerful voices and views to take into account, both at state and non-state levels.

But are the emerging democratic powers of India, Brazil, South Africa and others actually approaching human rights and freedom of expression differently when compared with Europe, the US or Japan, especially bearing in mind the huge diversity across these countries? And when European and American foreign ministries presume their countries are on the side of freedom and that India and Brazil are ‘swing states’ that must be brought onside and not allowed to slip into China’s or Russia’s sphere of influence, is this just a mixture of old-style geopolitical arrogance and ignorance? Could it be that the deepest economic crisis since the 1930s may result in changes in the neoliberal dominant economic model of the last three decades, rather than to the economic policies of Brazil, India or China?

We must first consider the key characteristics of the current multipolar economic order, sketching out how much and how little the dominant economic powers have changed and the implications for global views on core economic policies. Then we consider where the leading multipolar players sit in terms of a range of indicators of human rights, freedom of expression and political freedom and how this impacts on their positions in global fora on human rights. We conclude with an assessment of where the real changes lie, and where there is perhaps more continuity than some imagine.

FROM INDEX ON CENSORSHIP MAGAZINE

Global view: Who has freedom of expression? | News in monochrome: Journalism in India | Censorship: The problem child of Burma’s dictatorship

This article appears in the current issue of Index on Censorship, available now. For subscription options and to download the app for your iPhone/iPad, click here.

INDEX EVENTS

18 July New World (Dis)Order: What do Turkey, Russia and Brazil tell us about freedom and rights?

Multipolar economics: Is the West really on the way out?

For more than a decade, the media has been focused on the rise of the BRICS (Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa) and the demise of US–EU hegemony in the world economy, a dominance that has existed since the Berlin Wall came down in 1989. Predictions about the date China will overtake the US as the world’s largest economy have shifted dramatically: in 2001, the Economist reported that China could lead the world economy by 2028; more recent predictions suggest it will happen as early as 2020. The 2008 recession and its aftermath has turned world economic order upside down; there has been a huge and sustained depression in the developed world but hardly a hiccup in the relentless upward movement of the emerging markets. Jim O’Neill, economist at Goldman Sachs and inventor of the term BRICS, has recently coined the term “growth economies” to describe the larger group of medium-sized to large economies forecast to join the US, EU and Japan as the global economic powers in forthcoming decades. The major emerging powers now hold their own BRICS summits, with the most recent being hosted by South Africa, seen as the fifth country to play a key role in the future of global power, and held inDurban in April 2013.

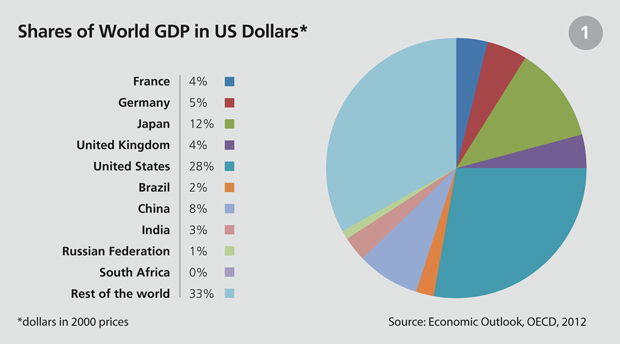

In this article, we focus on the five BRICS and the five largest western economies — the United States, Japan, Germany, the United Kingdom and France — in order to understand how the world economic order is changing and how that may shift global political dynamics, including the global discourse on human rights and freedom of expression. But first, is it true that the world economic order is changing? To answer that, we have to look at the size of the major economies in the world — what they produce or consume, measured by their gross domestic product (GDP). The story here is actually not as simple as some sections of the media suggest. According to one measure, there is not yet much sign of a changing world order. Graph 1, from the World Bank, shows the shares of world GDP in current prices in our 10 focus countries. The economic importance of these top ten among the 196 countries in the world is clear: in 2011, the 186 countries outside of our designated list of countries accounted for only one-third of global income. The hegemony of the US and EU is also clear. Combined, they account for slightly more than half of the world’s GDP. If we add in Japan, the total approaches two-thirds.

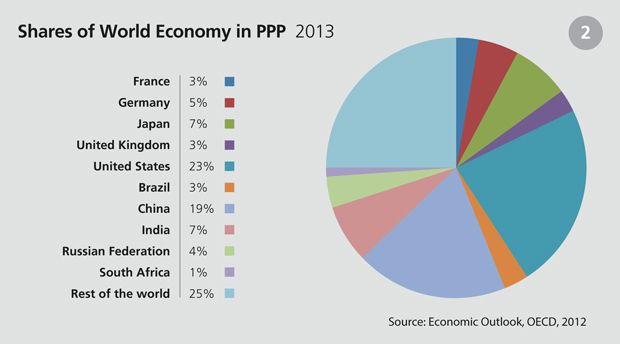

After the US and Japan, China is the third largest economy on this measure, but at 8 per cent of the total, it is substantially smaller than the US. So there is not much sign of a changing world order here, though China’s growing role and scale is clear. But it is a lot more complicated than that, and our evaluation of emerging global economic power depends on the measures used. In Graph 1, the five emerging markets accounted for about 15 per cent of world GDP in 2011 — with China the only one in the top five, though India is catching up on the UK and France. But the total of the five BRICS is much smaller than the US, Japan, or Germany, France and the UK combined. Even so, the BRICS’s very fast growth, combined with stagnation in the developed world, has meant that their share has expanded rapidly, almost doubling in the past decade. But the real crux of the matter is illustrated in Graphs 2 and 3, which moves from current prices to measurement in so-called purchasing power parity (PPP). PPP compares incomes between countries using an exchange rate calculated to equalise the spending power of money on a given bundle of goods in different locations. A given income can support very different standards of living in, for example, the USA, China and India, and PPP measures incomes across countries using a common yardstick in terms of living standards.

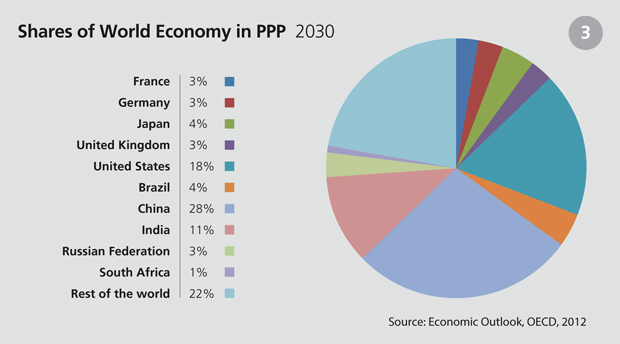

Most of the forecasts of the rising economic importance of the BRICS have relied on PPP measures, which overstate current economic power in poorer countries. Graphs 2 and 3 show us the shares in terms of world GDP, measured using PPP, of our ten countries in 2012, plus the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) forecasts up to 2030. PPP changes things a lot, and begins to explain the forecasts of a changing world order. China now represents 19 per cent of world GDP in 2013, and the five emerging giants more than 33 per cent. The US is still the largest economy in the world but represents less than a quarter of the total on its own.

The three European powers are 3–5 per cent of the world GDP each, equalling around half of the GDP of China and comparable to India and Brazil. Thus we see clear signs of an emerging new world order. When one looks at predictions of the world in 2030 wearing PPP lenses, it’s clear that things have changed significantly. By then, the European powers are all predicted to have shrunk, making up less than 9 per cent of the world economy combined. Japan is also predicted to half its world share, to only 4 per cent. Among existing major economies, only the US economy remains huge, still representing almost one-fifth of the world income. But what is striking is the rise of China, representing, by 2030, a larger share of the world economy than the US does in 2013, and by far the largest economy in the world. Moreover, emerging giants, notably India, exceed the European economies combined and are beginning to creep up on the US. The emerging economies combined, including South Africa, which by 2013 will be the size of a medium-sized EU economy, comprise 43 per cent of world GDP.

This does not mean that people in the new economies will all be as rich as in the US or EU. Predictions suggest that, in 2030, people living in the US will still be on average the richest among the larger countries in the world, with incomes in Europe and Japan similar to each other and somewhat below the US. Currently, incomes in our selected five emerging countries are at a third or less of Europe and, despite rapid growth, even the average Chinese consumer will only have about one-third of the average American’s spending power in 2030 (and that is when we measure this using PPP).

Levels of development and globalisation

Despite decades of rapid economic growth and the emergence of large-scale economies comparable or larger than those in the US and Europe, the new economic giants will still look very much like emerging or developing economies in 2030. Citizens are set to encounter problems associated with life in developing economies, including poverty, inequality, deficits in health and education services and overpopulation.

For Brazil, India and others, these problems seem likely to remain important in domestic debates for decades to come — and to influence attitudes to the global economic agendas. In particular, the new Asian economies tend to favour greater control over their domestic economies, less freedom for capital markets and greater reliance on state intervention to create jobs and growth. Moreover, the key stakeholders are not always the same as in developed western economies, with communist or leading party members dominating rather than voters and with business groups or state-owned firms — or family members — more important than shareholders.

Even so, the BRICS are unlikely to seek to change free trade and foreign direct investment because they are so integrated within it. Predictions about trade balances suggest that the current picture is not likely to change greatly up to 2030. Thus, deficit economies like the US, India and South Africa are predicted to be in a similar position 17 years hence, as are the big surplus countries — China and the US. However, it is also predicted that there will be some deterioration in the situation for France, Russia and Japan, largely because of their ageing populations and resource needs.

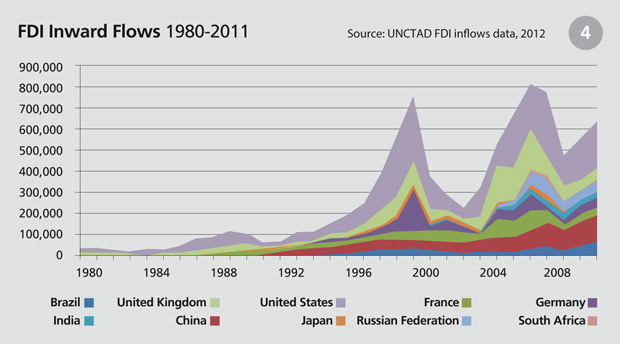

The emerging powers are also highly integrated into global capital flows. Graph 4 looks at foreign direct investment (FDI) flows since 1980. The new global economies are becoming increasingly important hosts for foreign investors, especially China, but also Brazil, India, South Africa and Russia. Thus, the world order with respect to trade and international investment is of great significance to the emerging powers, and they will surely increasingly demand their seat, voice and votes at all relevant summit tables. However, in this arena, their interests appear likely to be fundamentally aligned with those of the current leading powers.

Thus, the hype around a changing world economic order may be overstated. In current purchasing terms, the US, Japan and EU seem likely to be major players for decades to come, even if the emerging markets manage to remain on course without political unrest or economic instability. But the economies of Europe and Japan are set for a fairly sharp relative decline compared to the US and the emerging powers, especially China and India. In particular for the US, its more positive demographics may also underpin more continuity to political and economic power than is currently being suggested by many.

It is not clear whether and in what ways the new kids on the block will want to change things, even if they do manage to replace or supplement the declining powers of Europe and Japan at the tables of power. While not really accepting the free market ideology that has dominated for the past 30 years, they have as yet no coherent alternative narrative — and new voices arguing for industrial strategy or more regulation are now just as likely to be heard from Europe as from the BRICS. Most of the BRICSs’ economic issues in the coming decades will be concerned with global trade and investment, or will be domestic. And these economies are anyway all highly integrated into the global economy and so will be unlikely to want to rock the boat of free trade too much.

Freedom of expression and human rights in the multipolar world

What does all this imply for global human rights? Most of the main multipolar powers have signed up to a range of human rights declarations and/or treaties. Of the ten countries we are focusing on, all signed the major International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights — China alone has failed to ratify it. In theory, then, these countries have acknowledged a full range of rights, including freedom of expression, freedom of assembly and the right to privacy.

But when it comes to implementing these rights at home and respecting them abroad in terms of foreign and economic policies, or adopting positions at the UN or in regional organisations, then the reality of varying degrees of respect for human rights is clearly seen. The more recent and contested initiative of the International Criminal Court saw the US and Russia sign, but then not ratify, the Rome Statute. China and India did not even sign it.

Across the ten powers, it is the rising economic giant, China, which clearly has the worst human rights record domestically, followed by Russia. Freedom of expression is curtailed and controlled in China — whether it be media freedom, artistic freedom or freedom to protest. The digital age has in many ways challenged China’s, and other repressive states’, ability to censor effectively, with individuals gaining access to a whole set of tools to evade censorship. In some ways, it has opened up wider spaces for debate and information flows. Yet, because of the ease with which governments can collect and monitor individual users’ data, introduce firewalls and block websites, the digital age has also offered new opportunities for repression and censorship. In the US, UK and other democracies, the trend towards excessive use of over-wide monitoring of ordinary citizens’ electronic communications is a seriously worrying trend — even while the extent of blocking and direct censorship remains substantially better than in China and Russia.

The US and its allies have often been accused of hypocrisy in their promotion of human rights abroad. This is because their human rights agenda is either seen as a cloak for economic and security interests; because substantial violations of human rights occur both domestically in Western countries and as a result of these countries’ international interventions (from extraordinary rendition and Guantanamo to torture and degrading treatment in Iraq and Afghanistan); and/or due to inconsistent approaches to human rights, resulting in the US, the UK and others turning a blind eye to some cases of violations for reasons of realpolitik or other interests. China and Russia — and sometimes India, South Africa and Brazil — view human rights as a western construct that is used for inappropriate interference into the national sovereignty of individual states.

Yet in a compelling article published in the Indian Express in March 2013, the heads of Amnesty International in Brazil and India labelled the two countries as “underachievers in standing for human rights internationally”, contrasting their open societies with a lack of attention to rights abroad and calling on them to promote human rights internationally, not least through calling the US and EU to account.

Whether and to what extent the emerging democratic powers adopt strong international positions on freedom of expression and match those positions with respect for rights at home will have a major influence on the global discourse. In turn, it will help determine whether international statements, decisions and positions promote freedom of expression in the multipolar world, or whether they compromise and retreat.

A snapshot of political and media freedoms

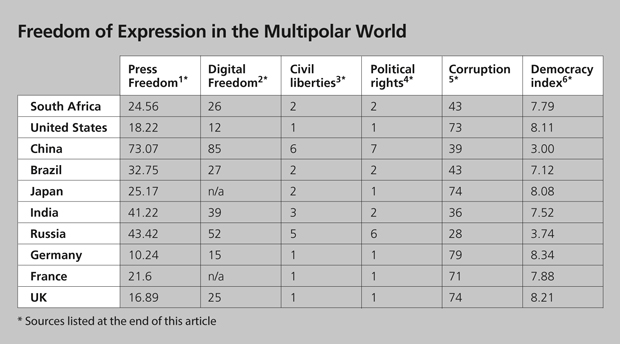

As we’ve seen, those countries with strong human rights records at home do not always respect rights abroad. At the same time, promoting free speech or press freedom at a global level or in another country will have more clout the more those powers arguing for free speech respect it in their home countries. What does the data say about how these multipolar actors actually perform with regard to human rights? The table presents a range of indicators of press freedom, digital freedom, political and democratic rights and corruption, which give a snapshot of the domestic positions of our ten countries. These indicators are not exact but they do give an outline of the state of various dimensions of freedom of expression across the ten mulitpolar powers. On press freedom, Germany and the US lead, followed by the UK and then France. South Africa is not far behind France and is rated freer than Japan, followed by Brazil, India and Russia, with China, unsurprisingly, lagging a long way behind. This snapshot suggests the old western powers have a better press freedom record, but with some of the emerging powers starting to catch up to some extent.

The Economist Intelligence Unit’s 2012 Democracy Index, meanwhile, puts France into the category of “flawed democracies”, only just ahead of South Africa. While Germany, the US, Japan and UK make it into the “full democracy” category (though 14 of the EU’s 27 member states do not), the US and Japan are near the bottom end, ranked 21st and 23rd respectively. Russia and China come in, respectively, at 122nd and 142nd on the list.

Freedom House’s digital freedom index also suggests a mixed picture across the old western powers and the democratic BRICS: the UK, Brazil and South Africa are almost level, while the US and Germany are substantially ahead, with India lagging, but well ahead of Russia and China.

There is a clear split between the old western powers and the BRICS when it comes to levels of corruption and indicators for broad civil and political liberties. Across the US, UK, France, Germany and Japan, there is fairly good performance on anti-corruption measures, while South Africa and Brazilcome a long way behind, but ahead of the lagging three, with particularly bad corruption records in India, China and Russia (the worst performer).

On political and civil liberties, with the exception of Japan (which misses a top score on civil liberties), the western five countries score a 1 on each of the two political and civil liberties indicators set out in the table. South Africa, Brazil and India score 2 (with India hitting a 3 for civil liberties) and Russia and China are at the bottom (between 5 and 7). But the diversity among them on corruption and civil and political liberties also suggests there is little basis across the BRICS for common positions on human rights, freedom of expression or a range of other political standards and choices — and given their different political systems, that is perhaps not unexpected.

Overall, the five western democracies come out somewhat ahead of South Africa, India and Brazil, but there are occasional overlaps across the eight countries, with one or other of the democratic BRICS sometimes ahead of one or two of the western powers when it comes to press or digital freedom. For now, the overall picture is one of the five western countries being ahead, at least domestically, on rights and liberties. Unsurprisingly, the picture of China is one of a repressive regime not respecting rights and civil liberties. That of Russia is almost, but not quite, as bad — and on media and digital freedom, it is ahead of China.

Respecting rights in a multipolar world

Any serious analysis of freedom of expression and defence of human rights needs to delve into the detail of different countries’ behaviour at home and internationally — indicators only provide an initial picture. As we see in the rest of this Special Report, there is a mixed picture across the multipolar world, especially across the democratic powers, with much that is positive and much that is worrying. And this more complex picture tells us that the multipolar democratic powers do not simply fall into a “good” group of the western powers, nor can players like India, Brazil and South Africa simply be categorised as “swing states” that the West must persuade to follow their lead. It is a more complex picture.

For example, in March 2013, the US, Brazil and India voted for the UN Human Rights Council’s resolution, which criticised (in watered-down fashion) Sri Lanka’s human rights record, while Japan abstained. At the International Telecommunications Union summit, a crucial digital forum held in Dubai in December 2012, Brazil and South Africa lined up with China, Russia (and a host of others) in a vote that many regarded as a stand against digital freedom, while India, the UK, the US, Germany, France and Japan abstained from the vote and will not implement the new treaty that resulted.

But before we see the western powers as leading on digital freedom — though this is a declared aim of their foreign policies — even a cursory look at behaviour at home shows worrying trends, from excessive surveillance in the US to high levels of requests to web host companies like Google and Twitter to remove content or provide information on individuals. These requests have come from all our five focus countries. In both India and the UK, meanwhile, old English laws from the 1930s are at the root of some excessive and inappropriate prosecutions of individual for social media posts and comments.

Press freedom is one area where the old western powers should shine (and where the indicators suggest they are ahead). Yet the UK is currently in the midst of a chaotic attempt to establish a new press regulator. Many politicians disagree with the majority of the press and, when MPs voted on whether to create a new regulator, Parliament crossed a red line.

The European Union sees press freedom under attack in a number of its member states and neighbours, but its attention has not diverted from the euro crisis in order to defend press freedom at home. And, under the Obama administration, there have been criminal prosecutions of journalists defending their sources. In Brazil, however, journalists face greater threats — by early May 2013, three journalists had been killed for publishing information about criminal organisations. The country is becoming increasingly dangerous for journalists.

If there are any simple conclusions out of this mixed and blurred picture, the main one is that, even in the face of inconsistencies, contradictions and hypocrisies, the genuinely democratic players amongst these ten countries are the ones that do promote freedom of expression and human rights, albeit to a patchy and imperfect degree, with China unsurprisingly the worst offender, and Russia’s autocratic version of democracy indicating rather little respect for rights.

The western five are currently ahead of the democratic BRICS on most indicators, but qualitative analysis starts to expose a more complex picture. It is also clear that both the old western powers and the emerging democratic powers are inconsistent and need to be held strongly to account. In foreign policy, they will need to tackle and improve their own records at home and abroad if any of them are to take up strong human rights and free expression leadership globally.

Conclusion

We are increasingly living in a multipolar world — both in an economic sense and geopolitically in terms of which powers are key voices at the summit tables and in international politics. It is a world that is still taking shape — China has indeed been catching up with the US, Japan and EU. These countries are still major economic players, while the smaller economies of India, Russia, Brazil and South Africa still have some way to go before their economic influence and scale starts to match that of Germany, France and the UK. But while the big western economies have more staying power than much of the multipolar hype may suggest, China will undoubtedly become very important. The EU and Japan are set to decline relatively and increasingly sharply in the next two decades.

In some ways, geopolitical shifts are ahead of the economic shifts, with the BRICS and other emerging powers demanding — and getting — their voice and seat at summits such as the G20, and holding their own BRICS summits, along with a diverse range of bilateral and regional summits.

In economic policy terms, there is little to suggest that the BRICS will be a united force, pushing for a different international economic ideology to the western economies, not least given their increasing degree of integration into the global economy. Indeed, as the fallout from the financial and euro crisis continues, any new debates on economic policy may be as likely to originate from western debates as from the BRICS.

From a human rights and freedom of expression perspective, functioning democracies unsurprisingly perform better than China’s authoritarian regime or the authoritarian democracy of Russia. The US, Japan, Germany, France and UK mostly outperform the democratic BRICS of South Africa, India and Brazil on key indicators of press freedom, corruption and civil liberties.

But it is not always a clear division: indicators conceal challenges within each country and more in-depth analysis is needed to identify inconsistencies and flaws in the positions these actors take on different human rights issues around the world.

The majority of these ten countries — as is the case for the G20 too — are democracies. The multipolar world can be one where universal human rights and freedom of expression are kept firmly on the agenda, and increasingly respected, if these democracies hold themselves and each other to account — and are held to account — at home and internationally.

Saul Estrin is professor of management and head of the Department of Management at the London School of Economics

Kirsty Hughes is chief executive at Index on Censorship. She tweets @kirsty_index

This article appears in the latest issue of Index on Censorship, The multipolar challenge to free expression, published today.