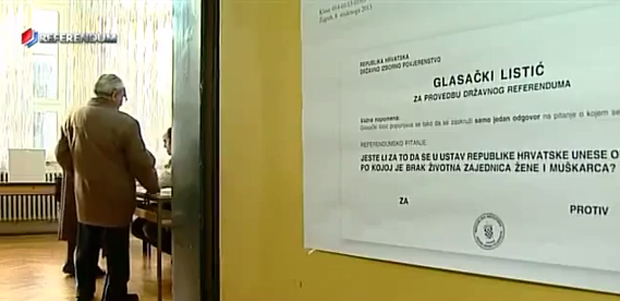

Croatians cast their votes on whether marriage should be constitutionally recognised as being between a man and a woman (Image: Mc Crnjo/YouTube)

Croatia’s voters moved Sunday to amend the country’s constitution to define marriage as being between a man and a woman. The campaign had been orchestrated by the country’s religious institutions. Sixty-five percent of voters supported a change that effectively bars gay marriage.

The campaign used some interesting and controversial tactics. Religious teachers in schools threatened students that they wouldn’t get a passing grade if they did not provide proof of their families’ support for the constitutional change. This was reported by an English language teacher from Split, the second largest city in Croatia, to the inspection body of the Ministry of Education around mid-November.

“If this is the situation in Split I believe it is even worse in smaller towns”, concluded the teacher who did not want to sign her name.

Following this, the media received numerous letters from school teachers confirming that religious teachers around Croatia were blackmailing students to make sure their family members vote “for the protection of the family” — the Catholic Church’s interpretation of the referendum question.

“If the president of the country and other public persons can talk about voting at the referendum why can’t a religious teacher do so?” commented Sabina Marunčić, senior advisor for religious education at the Croatian Education and Teacher Training Agency.

Since the call for a referendum on 8 November, the campaign has been the main topic of discussion in Croatia, despite the country facing a severe economic crisis and an unemployment rate of 20.3 per cent. While Croatian law defines marriage as a union between a man and a woman, this definition does not exist in the constitution. A recent announcement of a new law on same-sex partnerships has caused conservative movements to come together in the initiative “In the Name of Family”. They started spreading fear about gay marriage being legalised, despite the centre-left government showing no intention to do this. A 2003 law on same-sex partnerships has been seen as practically useless because it secures only a few, less important rights, and only after a relationship breaks down.

For weeks all anyone talked about was who will vote “for” and who will vote “against”, in the first national referendum in the Republic of Croatia set up by popular demand. The Social Democratic prime minister Zoran Milanović, President Ivo Josipović and numerous ministers all came forth against introducing the definition into the constitution. A large portion of powerful media was also openly against it. However, public opinion polls showed that 68 per cent of the citizens would vote for the proposal; 26 per cent against.

In the referendum campaign, the Catholic Church have firmly been advocating “for”. It has has a strong influence in the country of 4.29 million, with 86 per cent declaring themselves Catholic according to the latest census, released in 2011. The initiative “In the name of family” which has succeeded in gathering signatures of 740,000 citizens in order to hold a referendum is also linked to the Catholic Church.

“The church did not want to start the initiative for a referendum but it wholeheartedly accepted In the Name of Family, whose numerous members are conservative Catholics close to certain Croatian bishops,” says Hrvoje Crikvenec, editor of the religious portal Križ života (“Cross of Life”).

“However, I believe that the entire organisation and initiative is supported more by politics, that is, a marginal political right-wing party Hrast, than Croatian bishops. They have now become more involved in the campaign in the hope of what would for them be a positive outcome of the referendum, which would ultimately show them as winners.”

The initiative’s leaders do come from the non-parliamentary right-wing party Hrast, as well as conservative associations opposing the introduction of sex education in schools, artificial insemination and abortion. Some of them have been linked to Opus Dei, a secretive Catholic organisation which has been strengthening its presence in Croatia. In the Name of Family and the fight against a possible equal standing of homosexual and heterosexual marriages has provided them with the support of a larger portion of the public.

The Catholic Church has undoubtedly helped the success of a In the Name of Family. Signatures were gathered in front of churches and elsewhere, even in universities. Cardinal Josip Bozanić had written a note instructing priests to encourage believers in masses to attend the referendum and vote for the definition of marriage as a union between a man and a woman. Group prayers for its success were also organised throughout Croatia in the lead up to the vote.

“We can’t blame the bishops for advocating the referendum from the altar because this is a part of the church’s program. They are more entitled do so than to say who to vote for at the elections, which they also do. However, it is inadmissible for religious teachers to influence children in schools,” university professor of philosophy and political commentator Žarko Puhovski says.

Despite Croatia being a majority Catholic country, every fourth marriage ends in divorce and a decreasing number of couples are deciding to marry.

“The church’s influence on citizens is far greater regarding political than moral views. Church morality is accepted in principle, but political views supported by the church gain additional power. That is why the referendum is causing a short-term increase in the influence of the church, which has for years been weakening,” Puhovski explains.

Church leaders are often complaining about the non-existent dialogue with the current, left-wing government, especially regarding the issues they consider to be related to religion – education of children, family care and marriage.

“The ultimate success of this referendum is in showing the power of the church in Croatia. It has shown the government that it can move masses of people so in the future, the government will have to think carefully before making any decision which could harm their interests,” said a group of Roman Catholic theologists in a joint letter made public on 29 November.

“The relationship between the church and the state has mostly been disturbed by militant statements of individuals from the Catholic Church leadership, which seem to be best served with a one common mindset rather than political and worldview pluralism,” sociologist and ex-ambassador for the Holy See, Ivica Maštruko says.

“We are not dealing with a normal criticism of the current social state and relations, but bigotry, inappropriate discourse and civilisational and religious malice,” Maštruko added.

An example of such a discourse is provided by reputable former minister and theologist Adalbert Rebić who, earlier this year, was quoted as saying: “The conspiracy of faggots, communists and dykes will ruin Croatia.” Pastor Franjo Jurčević was convicted for publishing homophobic and extremist posts on his blog.

But in the campaign for the referendum the Catholic Church was joined by representatives of the other most influential religious communities in Croatia – Orthodox Christians, Muslims, Baptists and the Jewish community Bet Israel. Together they supported the referendum and invited the believers to vote in order to “secure a constitutional protection of marriage”. Religious communities in Croatia are usually rarely seen forming such shared views.

“The most interesting thing is the agreement between the Catholic Church and the Serbian Orthodox Church which have in the past twenty years completely missed the chance to initiate reconciliation, dialogue and co-existence during and after the wars in ex-Yugoslavia. Religious communities in the region can obviously agree only when they find a common enemy, which in the case of this referendum are LGBT persons,” Cirkvenec says.

Žarko Puhovski considers it indicative that religious communities in Croatia succeed in forming shared views only with regards to sexual morality.

“They have failed to reach a consensus on any other moral or political issue,” he concludes.

This article was published on 2 Dec 2013 at indexoncensorship.org