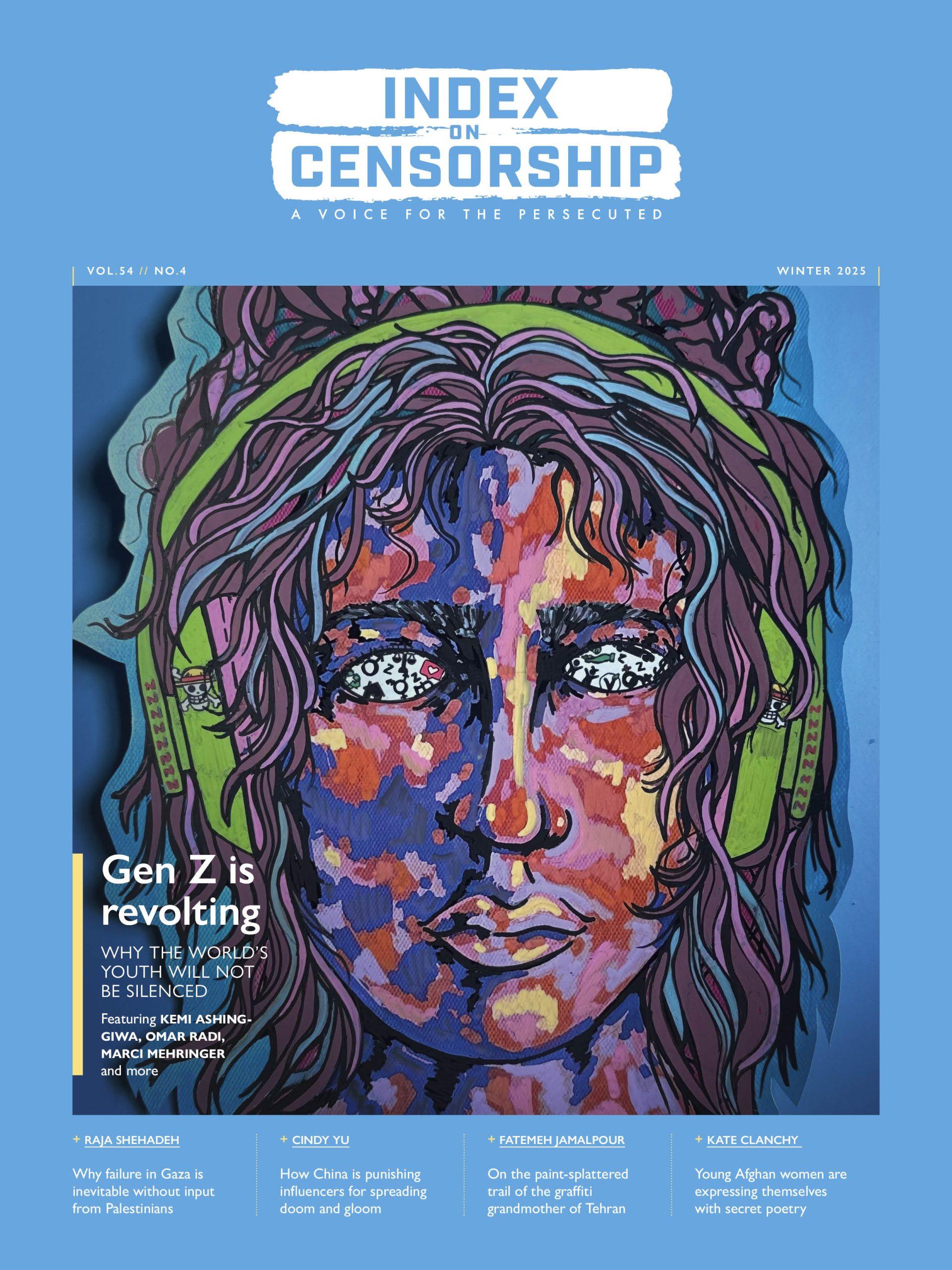

Supporters of General Sisi in December 2013 (Photo: Sharron Ward / Demotix)

National Police Day, 25 January 2011. Years of police brutality is being challenged by activists in Tahrir Square. Volleys of tear gas mark the beginning of the Egyptian revolution, even if nobody knows it yet.

“The police were in control of everything that day,” journalist Muhammad Mansour remembers. “But it was a sign. I remember feeling like that day was a test for the police…it was a difficult fight.”

But three years on and Egypt looks a very different place. On Friday at least 64 people were killed nationwide – most of them with live ammunition – and 1,076 people arrested, according to official figures. Informal counts put the number of deaths closer to 100.

While revolutionary protesters were shot dead in downtown Cairo, including an April 6 activist – Sayed Wezza – who campaigned for the Tamarod movement against former Islamist President Mohamed Morsi, over 40 Muslim Brotherhood supporters were gunned down in the north-east of the capital. In both cases, authorities allegedly resorted to using near-immediate lethal force to disperse protests and, activists claim, silence dissent.

One revolutionary march from Mostafa Mahmoud square was dispersed quickly, another outside the Journalists’ Syndicate faced a similar reaction. In both cases, police reacted minutes after marches started moving. A statement from an April 6 Youth Movement organiser, texted minutes after the dispersal started, alleged the police had used live ammunition to disperse peaceful protests. “This is not the Egypt we are looking for,” it said.

“We didn’t even reach three blocks from the syndicate before we came under attack,” Revolutionary Socialist activist Tarek Shalaby says. After the tear gas started, he ran into a side-street as police vans hurtled round corners firing off tear gas and bullets. Shalaby then picked up a poster of Abdel Fattah al-Sisi and got out. Not far from the clashes, Shalaby was then questioned by a Sisi supporter who was keen to know why his poster of the general was ripped.

National Police Day was once a stage-managed celebration of state authority. This year’s 25 January felt like that and more. Egyptians poured into Tahrir Square to the ubiquitous sounds of pro-army anthem ‘Teslam al-Ayadi.’ Crowds roared as military helicopters breezed over rooftops dropping Egyptian flags and vouchers for basic goods. For many, it was a stage-managed endorsement of General Abdel Fattah al-Sisi’s expected bid for the presidency – but one a majority of Egyptians wholeheartedly support.

While police attacked revolutionary and Brotherhood protests, the Saturday celebrations also revealed a street-level willingness to act side by side with the police.

It’s a role encouraged by state and independent media, Shalaby claims, referring to calls by Egyptian news channels for members of the public to citizen’s arrest potential Brotherhood supporters, or people looking to disrupt the day. Given Egypt’s currently hyper-nationalist state narrative, that leaves activists, Brotherhood members as well as journalists and foreigners privy to abuses.

An Association for Freedom of Thought and Expression (AFTE) report recorded 36 violations against journalists and photojournalists on January 25. Vigilante justice, and impunity for those carrying it out, is a growing problem.

“I was interviewing the ‘Bride of Sisi’, as she called herself, when a crowd gathered around me and another journalist and accused us of working for a ‘terrorist’ news channel,” journalist Nadine Marroushi wrote in a London Review of Books blog. While interviewing inside the square, Marroushi and Daily News Egypt journalist Basil al-Dabh were accused of working for Al-Jazeera, insulted and physically assaulted. The police intervened and detained them for their own safety. “They took us away to a building just off the square and told us to hide there for an hour until the crowd calmed down.”

A video from a nearby street also showed a police officer telling a MBC Egypt camera camera to “move that camera…or I’ll tell the crowds you’re from Al-Jazeera.” The Qatari broadcaster has become deeply unpopular with many Egyptians, seen as one arm of the Muslim Brotherhood, itself identified as a terrorist organization in late December. Five Al-Jazeera journalists are currently in prison on charges of spreading false news and membership of a terrorist organization.

In a separate incident Matthew Stender, who went down to Tahrir to photograph the celebrations, was assaulted after running over to see where two Spanish journalists were being mobbed. Stender in turn was attacked. This time the army intervened and held him in a nearby room for an hour. While the Spanish journalists looked “quite roughed up,” Stender says, two other Egyptian journalists also accused of working for Al-Jazeera showed signs of “substantial injuries… [one] had a gash in the back of his head.”

In the run-up to January 25 this year, interim President Adly Mansour declared the “end of the police state in Egypt”. Meanwhile a damning report by Amnesty International last week condemned post-Morsi “state violence unseen even during the first 18 days of the ‘January 25 Revolution’,” expressing concerns that authorities are “utilizing all branches of the state apparatus to trample on human rights and quash dissent.” And the growing trend of violent protest dispersals, politicized detentions and home arrests suggest that Egypt is actually witnessing a return to old practices, only today they are dressed up in a fresh narrative indelibly stained red, white and black.

This article was published 0n 27 January at www.indexoncensorship.org