The law of libel, privacy and national “insult” laws vary across the European Union. In a number of member states, criminal sanctions are still in place and public interest defences are inadequate, curtailing freedom of expression.

The European Union has limited competencies in this area, except in the field of data protection, where it is devising new regulations. Due to the impact on freedom of expression and the functioning of the internal market, the European Commisssion High Level Group on Media Freedom and Pluralism recommended that libel laws be harmonised across the European Union. It remains the case that the European Court of Human Rights is instrumental in defending freedom of expression where the laws of member states fail to do so. Far too often, archaic national laws have been left unreformed and therefore contain provisions that have the potential to chill freedom of expression.

Nearly all EU member states still have not repealed criminal sanctions for defamation – with only Croatia,[1] Cyprus, Ireland, Romania and the UK[2] having done so. The parliamentary assembly of the Council of Europe called on states to repeal criminal sanctions for libel in 2007, as did both the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE) and UN special rapporteurs on freedom of expression.[3] Criminal defamation laws chill free speech by making it possible for journalists to face jail or a criminal record (which will have a direct impact on their future careers), in connection with their work. Many EU member states have tougher sanctions for criminal libel against politicians than ordinary citizens, even though the European Court of Human Rights ruled in Lingens v. Austria (1986) that:

“The limits of acceptable criticism are accordingly wider as regards a politician as such than as regards a private individual.”

Of particular concern is the fact that insult laws remain in place in many EU member states and are enforced – particularly in Poland, Spain, and Greece – even though convictions are regularly overturned by the European Court of Human Rights. Insult to national symbols is also criminalised in Austria, Germany and Poland. Austria has the EU’s strictest laws in this regard, with the penal code criminalising the disparagement of the state and its symbols[4] if malicious insult is perceived by a broad section of the republic. This section of the code also covers the flag and the federal anthem of the state. In November 2013, Spain’s parliament passed draft legislation permitting fines of up to €30,000 for “insulting” the country’s flag. The Council of Europe’s Commissioner for Human Rights, Nils Muiznieks, criticised the proposals stating they were of “serious concern”.

There is a wide variance in the application of civil defamation laws across the EU – with significant differences in defences, costs and damages. Excessive costs and damages in civil defamation and privacy actions is known to chill free expression, as authors fear ruinous litigation, as recognised by the European Court of Human Rights in MGM vs UK.[5] In 2008, Oxford University found huge variants in the costs of defamation actions across the EU, from around €600 (constituting both claimants’ and defendants’ costs) in Cyprus and Bulgaria to in excess of €1,000,000 in Ireland and the UK. Defences for defendants vary widely too: truth as a defence is commonplace across the EU but a stand-alone public interest defence is more limited.

Italy and Germany’s codes provide for responsible journalism defences instead of using a general public interest defence. In contrast, the UK recently introduced a public interest defence that covers journalists, as well as all organisations or individuals that undertake public interest publications, including academics, NGOs, consumer protection groups and bloggers. The burden of proof is primarily on the claimant in many European jurisdictions including Germany, Italy and France, whereas in the UK and Ireland, the burden is more significantly on the defendant, who is required to prove they have not libelled the claimant.

Privacy

Article 8 of the European Convention on Human Rights protects the right to a private life throughout the European Union. [6] The right to freedom of expression and the right to a private right are often complementary rights, in particular in the online sphere. Privacy law is, on the whole, left to EU member states to decide. In a number of EU member states, the right to privacy can restrict the right to freedom of expression because there are limited protections for those who breach the right to privacy for reasons of public interest.

The media’s willingness to report and comment on aspects of people’s private lives, in particular where there is a legitimate public interest, has raised questions over the boundaries of what is public and what is private. In many EU member states, the media’s right to freedom of expression has been overly compromised by the lack of a serious public interest defence in privacy law. This is most clearly illustrated by the fact that some European Union member states offer protection for the private lives of politicians and the powerful, even when publication is in the public interest, in particular in France, Italy and Germany. In Italy, former Prime Minister Silvio Berlusconi used the country’s privacy laws to successfully sue the publisher of Italian magazine Oggi for breach of privacy after the magazine published photographs of the premier at parties where escort girls were allegedly in attendance. Publisher Pino Belleri received a suspended five-month sentence and a €10,000 fine. The set of photographs proved that the premier had used Italian state aircraft for his own private purposes, in breach of the law. Even though there was a clear public interest, the Italian Public Prosecutor’s Office brought charges. In Slovakia, courts also have a narrow interpretation of the public interest defence with regard to privacy. In February 2012, a District Court in Bratislava prohibited the distribution or publication of a book alleging corrupt links between Slovak politicians and the Penta financial group. One of the partners at Penta filed for a preliminary injunction to ban the publication for breach of privacy. It took three months for the decision to be overruled by a higher court and for the book to be published.

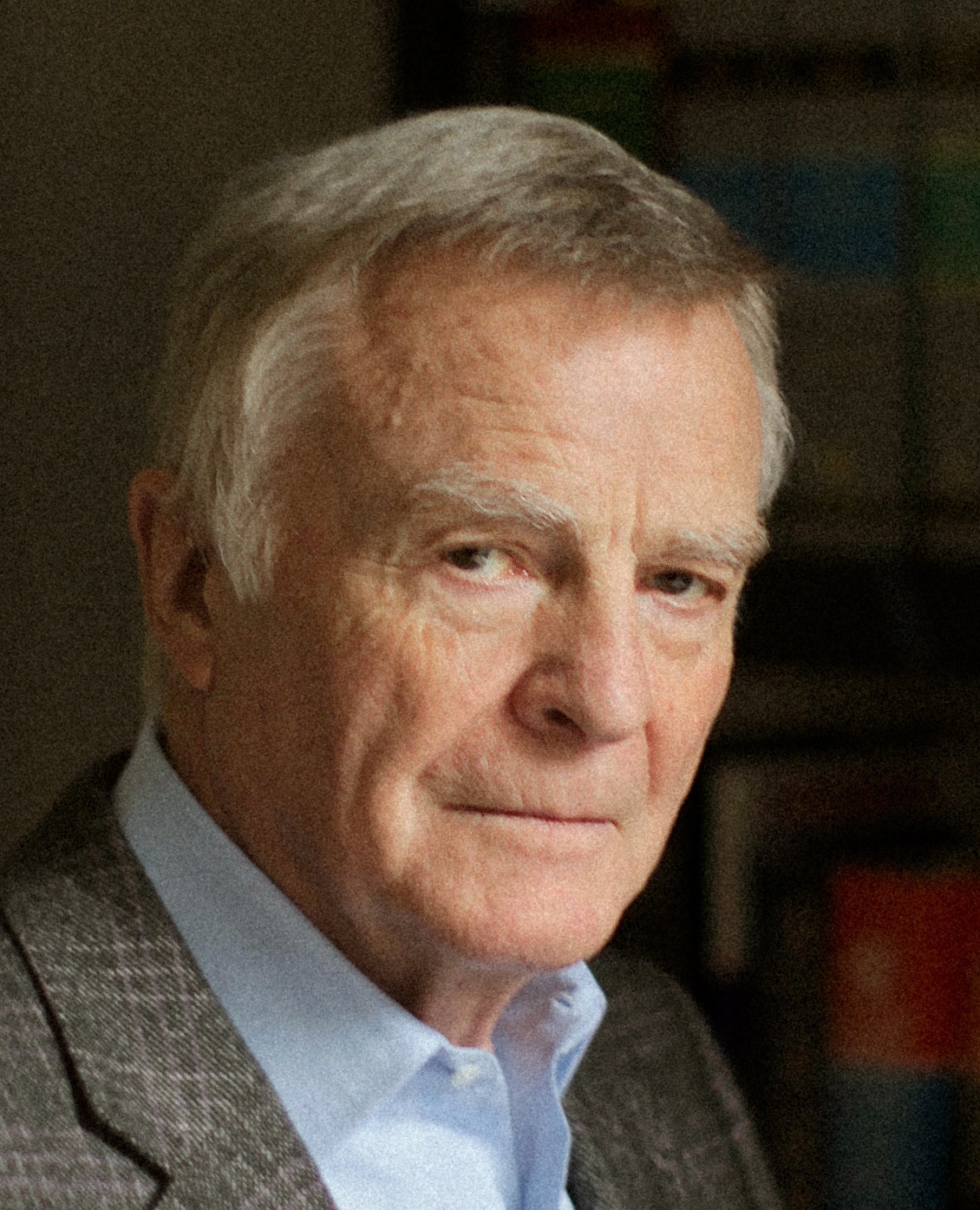

The European Court of Human Rights rejected former Federation Internationale de l’Automobile president Max Mosley’s attempt to force newspapers to give prior notification in instances where they may breach an individual’s right to a private life, noting that the requirement for prior notification would likely chill political and public interest matters. Yet prior notification and/or consent is currently a requirement in three EU member states: Latvia, Lithuania and Poland.

Other countries have clear public interest defences. The Swedish Personal Data Act (PDA), or personuppgiftslagen (PUL), was enacted in 1998 and provides strong protections for freedom of expression by stating that in cases where there is a conflict between personal data privacy and freedom of the press or freedom of expression, the latter will prevail. The Supreme Court of Sweden backed this principle in 2001 in a case where a website was sued for breach of privacy after it highlighted criticisms of Swedish bank officials.

When it comes to data retention, the European Union demonstrates clear competency. As noted in Index’s policy paper “Is the EU heading in the right direction on digital freedom?“, published in June 2013, the EU is currently debating data protection reforms that would strengthen existing privacy principles set out in 1995, as well as harmonise individual member states’ laws. The proposed EU General Data Protection Regulation, currently being debated by the European Parliament, aims to give users greater control of their personal data and hold companies more accountable when they access data. But the “right to be forgotten” clause of the proposed regulation has been the subject of controversy as it would allow internet users to remove content posted to social networks in the past. This limited right is not expected to require search engines to stop linking to articles, nor would it require news outlets to remove articles users found offensive from their sites. The Center for Democracy and Technology referred to the impact of these proposals as placing “unreasonable burdens” that could chill expression by leading to fewer online platforms for unrestricted speech. These concerns, among others, should be taken into consideration at the EU level. In the data protection debate, freedom of expression should not be compromised to enact stricter privacy policies.

This article was posted on Jan 2 2013 at indexoncensorship.org

[1] Article 208 of the Criminal Code.

[2] Article 168(2) of the Criminal Code.

[3] Article 248 of the Criminal Code prohibits ‘disparagement of the State and its symbols, ibid, International PEN.

[4] Index on Censorship, ‘UK government abolishes seditious libel and criminal defamation’ (13 July 2009)

[5] More recent jurisprudence includes: Lopes Gomes da Silva v Portugal (2000); Oberschlick v Austria (no 2) (1997) and Schwabe v Austria (1992) which all cover the limits for legitimate criticism of politicians.

[6] Privacy is also protected by the Charter of Fundamental Rights through Article 7 (‘Respect for private and family life’) and Article 8 (‘Protection of personal data’).