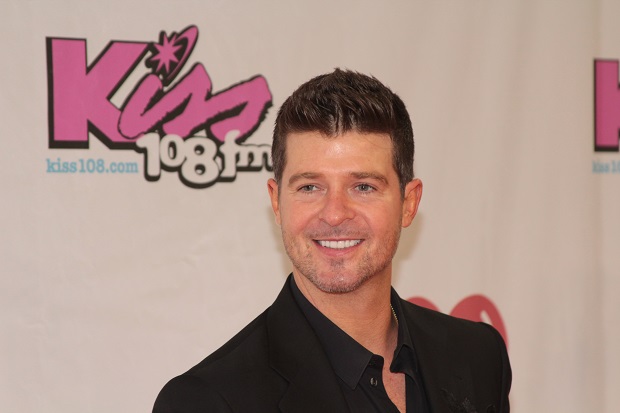

Robin Thicke’s Blurred Lines song has been banned in at least 20 student unions after it was released in March 2013. (Image: George Weinstein/Demotix)

I consider myself to be privileged to have the job that I have-I am a university lecturer who teaches Popular Music Culture to undergraduates and post-graduates. This is a subject that is popular among students because the majority of them like music and have an opinion on it. What I love most about my job is the range of interesting conversations my students and I have around popular music and its impact on culture, politics and society.

Music is ubiquitous and it touches people of all cultures, classes and creeds in a multitude of ways. What comes out of the discussions I have highlights both the joy and the anger it can evoke. Some of those discussions can bring forward some sensitive, awkward and challenging opinions and issues but what they do succeed in doing is highlighting issues that we as adults can explore, discuss, argue, rationalise and at time agree to differ on-but in a mature and accepting way, appreciating that we are all different.

So during my lecture on popular music and gender back in November 2013 I opened up a discussion around Robin Thicke’s summer release “Blurred Lines”. I feel no real need to go into any great detail about the fastest selling digital song in history and biggest single hit of 2013. Why? Because the controversy surrounding this song, such as misogynistic positioning with “rapey” lyrics that excuse rape and promote non-consensual sex and, among many other accusations, the promotion of “lad culture”, is abundant on the internet.

My students’ views on this song, and accompanying video mixed with both females and males defending the song and Thicke’s counter argument of it – promoting feminism, it being tongue in cheek and a disposable pop song – to those who, again both male and female, just wanted to castrate him for putting women’s rights and equality back into the dark ages.

Now the scene in the lecture theatre had been set I wanted to garner from them views on what I considered to be equally, if not more important – the issue that over 20 university student unions in the UK had banned the song from being played in their student union bars and union promoted events. This includes the prevention of in-house and visiting DJs playing it on student union premises and ,in some cases, the song not being aired on student union radio and TV stations’ playlists. In their defence the majority of these universities decided to ban after complaints from some of their students, but I am yet to determine whether all these universities reached this decision after an open and democratic process of consensus through voting or otherwise.

What I did find interesting among the many statements from presidents and vice-presidents of the student unions was one given to the New Musical Express, in November 2013, by Kirsty Haigh, the vice president of Edinburgh University Student Association.

The decision to ban ‘Blurred Lines’ from our venues has been taken as it promotes an unhealthy attitude towards sex and consent. EUSA has a policy on zero tolerance towards sexual harassment, a policy to end lad culture on campus and a safe space policy-all of which this song violates”.

However what Haigh does not go on to explain is exactly how this song does that. I am also intrigued by the comment about a policy to end ”lad culture” as Haigh does not allude to a clearly defined set of parameters specifying what counts as ”lad culture/banter”. One might ask if identifying a specific gender (lad) is this not targeting and discriminating against that gender?

I am struggling to find what constitutes ”lad culture” as opinions differ, however the National Union of Students’ That’s What She Said report published in March 2013 defines it as: “a group or ‘pack’ mentality residing in activities such as sport and heavy alcohol consumption and ‘banter’ which was often sexist, misogynistic, or homophobic”. But does lad culture equate to sexual harassment-is there a connection or is this creating guilt by association? Some critics claim that ”lad culture” was a postmodern transformation of masculinity, an ironic response to ”girl power” that had developed during the noughties.

Allie Renison’s article Blurred lines: Why can’t women dance provocatively and still be empowered?, published in The Telegraph in July 2013, states that “Teenage girls and grown women spend countless hours confiding in each other about the finer details of physical intimacy, and I can safely say that even without a sex-obsessed pop culture this would still be the case.”

This has to some degree been confirmed by one of my students who is a member of the university girls’ hockey team and girls’ football team. She says that they go out as a group, taking part in activities such as sport and heavy alcohol consumption and banter which is often sexist and misandry and involves intimate commentary on the male anatomy and men’s sexual prowess.

So would that then constitute “ladette” culture or “girl power” culture? Do EUSA have a policy to end ladette culture on their campus?

But this isn’t really the core issue here; the issue is around censorship on campus, what constitutes a fair and balanced approach to these issues and where you draw the lines. Thirty years ago student unions were complaining about, and rallying against, censorship-now they are the ones doing the censoring. So where does this leave the issue of censorship?

Starting with music, has Blurred Lines been singled out or do those twenty university student unions have a clear policy on banning songs that might include Prodigy’s Smack My Bitch Up, Jimi Hendrix’s Hey Joe (condoning the shooting of women who cheat on their men), Robert Palmer’s Addicted To Love (the lyrics could be seen to suggest date rape), Rolling Stones’ Under My Thumb, or Britney Spear’s Hit Me Baby One More Time? The list could go on and on, including songs that incite violence, racism or revolution. Do student unions around the country have concise and definitive lists of songs that should be banned or censored or is it a matter for a small group of elected people? And when you leave a group of people to act as moral arbiters then how do you control their decision making power?

Did we not collectively settle this matter in the 90s? Didn’t we conclude that outrage over pop music is a music marketer’s dream and inevitably increases sales for the artist? Aren’t popular music lyrics supposed to be challenging, full of danger and ambiguity? And do we only stop at popular music?

It could be argued that Mozart’s Don Giovanni revels in the actions of a rapist as does Britten’s Rape of Lucretia, and what of literature, do we ban Nabokov’s Lolita, Oscar Wilde’s Salome? Shouldn’t student unions be picketing concert halls, storming the libraries and art collections of universities and start demanding the removal of offensive material or at worst the burning of books and paintings in homage to a misguided Ray Bradbury envisioned cultural pogrom? If you are going to start banning or censoring cultural artefacts then please at least have some sort of consistency otherwise you leave yourself open to criticism.

So is this censorship? I would argue it is. If policy prevents a visiting DJ from playing a particular song at a student union bar, because some people do not approve of it, then that is censorship. I myself do not disagree with the criticism of the lyrical content of Blurred Lines, or condone them, though one could argue about their potential polysemic interpretation. What this highlights is perhaps an inconsistency in the processes of censorship by the student union.

Working in a university, I strongly believe that one of the core purposes of the academy is to create a space to allow young adults, on their journey of personal development, to explore their own opinions and prejudices, while considering those of others. A space where they can hear a multitude of views and draw their own conclusions from them; engage in constructive debate, work these issues through. Universities, of all places, should foster a culture of free speech and free expression wherever reasonably expected. Yes, there are always going to be challenges to what is appropriate and acceptable, whatever those challenges are the banning or censoring of material always has to be done within the law. That is how we develop as individuals and a society.

This article was published on February 26, 2014 at indexoncensorship.org