“The book, which is out of stock with us, shall not be reissued until the concerns are addressed for an acceptable resolution of the whole matter,”- says a 10 March statement from Aleph Book Company, publisher of Wendy Doniger’s “On Hinduism”.

“The book, which is out of stock with us, shall not be reissued until the concerns are addressed for an acceptable resolution of the whole matter,”- says a 10 March statement from Aleph Book Company, publisher of Wendy Doniger’s “On Hinduism”.

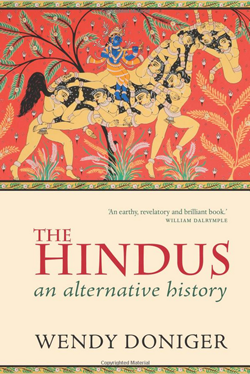

A panel of four independent scholars will review the book, and then parley on equal terms with Dina Nath Batra, the same person who vanquished Doniger’s previous book “The Hindus: An Alternative History”.

Aleph’s optimism about some amicable solution is misplaced. Emboldened by Penguin India’s surrender the first time round, Dina Nath Batra’s second onslaught was more strident, and if examined critically, his claims, more preposterous. And nothing in his conduct permits one to hazard a guess about ceding even an inch of territory.

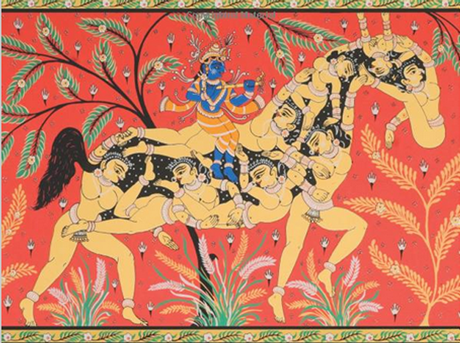

The legal notice slapped by Batra is a bullying rag, littered with random phrases and sentences which cannot be strung together by any stretch of logic. Parsing it, one gets to know how hurtful and offensive the “sexual thrust” of Doniger’s “titillating sexual tapestry” is. In her book which Aleph hails as a “magisterial volume”, a “scholarship of the highest order, and a compelling analysis of one of the world’s great faiths”, Doniger talks about Brahmin men’s monopolisation of Sanskrit, their oppression of women and Dalits (Untouchables), and a religious philosopher’s exhortation to overthrow the caste system and shatter the taboo against beef consumption. Then there is this limerick, whose truth many Indians would grudgingly testify to:

A Hindu who didn’t like kama

Refused to take off his pajama,

When his bride’s lustful finger

Reached out for his linga

He jumped up and ran home to Mama.

Batra and his acolytes’ litany of complaints can go on, and one can continue harping on Hinduism’s inherently pluralistic and tolerant character. But, now the crux of the problem is something different. The bigoted Hindus claim they are “law-abiding citizens” and have only sought to enforce the protection provided by the law, and even Penguin tried to hide behind the charade of “we respect the law of the land”. Which should naturally lead one to inquire -– what do the legal provisions say, and how have the courts interpreted them over the years?

Censorship mavens as “Law-abiding citizens”? Not really.

At first blush, it might seem that Sections 295A, 298, and 153A of the Indian Penal Code demonstrate excessive solicitude for hurt religious sentiments, shut out any independent critical inquiry and punish satire. However, “deliberate and malicious acts intended to outrage” remains an essential ingredient, and this remains the pivot on which freedom of expression rests. Agreed that Doniger’s telling of the scriptures does employ biting satire, and some of her statements are indeed tongue-in-cheek. Because she challenges the hegemonic interpretation of the self-appointed custodians of the faith, they accuse her of gratuitous provocation and making scurrilous statements.

Fortunately, the law takes a different view, and quite assertively so. Indian courts have a long tradition of protecting and upholding the right to express contrarian views on religion and the scriptures.

In 1924, a pamphlet titled Rangeela (“colourful”, in Hindi) Rasul, claiming to describe the real events of Prophet Mohammed’s life did the rounds in pre-Partition Punjab. Muslims were livid, a communal conflagration seemed imminent, but the Punjab High Court upheld the writer’s right to freedom of expression. Section 153-A, the court held, was intended to prevent riotous attacks against members of a particular religious community, and not to bar polemics, even if the remarks were undoubtedly satirical and scurrilous.

When in 2001 the government proscribed posters depicting the Ram Katha (an alternative narrative of the Ramayana) in the Buddhist and Jain traditions, the Delhi High Court put its foot down on not allowing free speech to be trampled by insular bigotry. Regarding the use of stray passages to demand censorship, the Delhi High Court’s 2001 judgement is illuminating. A single phrase — “that militant Ram used to stoke Hindu Muslim hatred in India today” from a documentary on the Ramayana was picked on by the censors. Not only did the court provide a judicial shield to diversity of interpretations, it asserted that random passages are insufficient to justify restrictions on free speech. Any restriction must be justified “on the anvil of necessity and not on the quicksand of convenience or expediency,” or on the unsubstantiated apprehensions of communal violence.

It would be partially speculative to single out all the real or purported reasons for Penguin’s surrender. But to exonerate bigots on the basis of their disingenuous claim of adhering to the law would set a pernicious precedent, paving the way for more books to be “pulped” and authors to be silenced.

This article was published on 14 March 2014 at indexoncensorship.org