In 2013, by way of abundant caution, Harper Collins India decided to pixellate a total of nine panels, including all the close-ups of penises in David Brown’s graphic novel “Paying for It.” While the content, in which Brown narrated his encounters with sex-workers, was left untouched, the publishers were wary of India’s laws against obscenity which make the depiction of nudity almost verboten. This is because a sheet of prudery covers any sexual expression and also governs the legal regulation of sexual speech.

Hence, many welcomed the Indian Supreme Court’s February 2014 ruling that merely because a picture showed nudity, it wouldn’t be caught within the obscenity net- “a picture can be deemed obscene only if it is lascivious, appeals to prurient interests and tends to deprave and corrupt those likely to read, see or hear it,” and having a redeeming social value would save it from being censored.

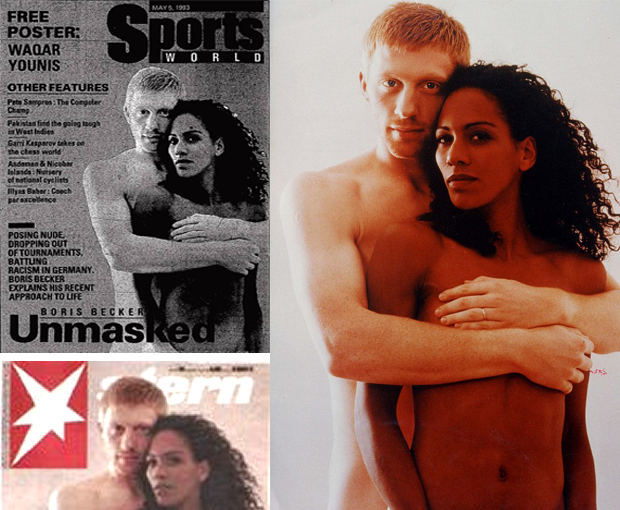

The decision came in an appeal filed in 1993. Sports World, a magazine published from Calcutta, had reproduced the photo on the cover of German magazine Stern. In that photograph, Boris Becker had posed nude with his then fiancée Barbara Feltus; it was his way of protesting against the racist abuse the couple were being subjected to. A solicitous lawyer dragged Sports World to court, alleging that the morals of society and young, impressionable minds were in jeopardy. He cited Section 292 of the Indian Penal Code which prohibits and penalises any form of expression tending towards prurience and encouraging depravity in the readers or viewers. The court rejected the contention, holding that the Hicklin’s Test for determining obscenity has become obsolete, besides imposing unreasonable fetters on the freedom of expression. This test, formulated by the House of Lords in 1868 in Regina v. Hicklin stipulated that ‘‘The test of obscenity is whether the tendency of the matter charged as obscenity is to deprave and corrupt those whose minds are open to such immoral influences and into whose hands a publication of this sort may fall.’’

Instead, the United States Supreme Court’s ruling in Roth – wherein “contemporary community standards” were held to be a far more reasonable arbiter, was directed to be adopted. The court also affirmatively cited the decision in Butler which, while upholding the test in Roth, added that anything which showed undue exploitation of sex or degrading treatment of women would remain prohibited.

While the Hicklin’s Test being jettisoned is a cause of relief, the judgement by no means can be held as finally freeing Indian law from the shackles of “comstockery.” George Bernard Shaw had coined this term in 1905 while raging against Anthony Comstock who had taken it upon himself to rid American society of vice. For Comstock, lust and sexual desire were abhorrent, and as he candidly proclaimed anything which even remotely arouses any sexual desire was to be dealt with in the most stringent manner. No wonder he had called Shaw an “Irish smut-peddler” in retaliation.

Gymnophobia, or the fear of nudity, isn’t something new to India’s Supreme Court. Also, it has always been female nudity and the fear of sexual desire which have governed the Court’s opinions. Its image-blaming position has repeatedly been used to reinforce the assumption that sexually explicit images trigger urges in men for which they cannot be held responsible. Depictions of nudity WERE condoned only if they achieved some “laudable social purpose” such as encouraging family planning or making people aware of caste-based atrocities. As Martha Nussbaum points out, collapsing the “disgust” for the nude female body with male sexual arousal and regarding sex as something furtive and impure results in the revulsion being projected on to the female body, thereby making the legal definition of obscenity collude with misogyny.

The present decision is no different. Because Feltus’ breasts were covered by Becker’s arm, and also because Feltus’ father was the photographer, it was held that only the most depraved mind would be aroused and titillated by the magazine cover. Most troubling of all is the overt reliance on contemporary community standards. True, that Indian society has evolved since 1993, but as Brenda Cossman details the scene in Canada in Butler’s aftermath, community standards became a rubric for majoritarian sexual hegemony, resulting in persecution and censorship by prudish vigilantes. And of course, it goes without saying that the search for “redeeming social value” usually ends at puritans’ doorsteps.

Comstockery’s tattered banner, emblazoned with “Morals, not art!” flies aflutter in India.

This article was posted on 22 April 2014 at indexoncensorship.org