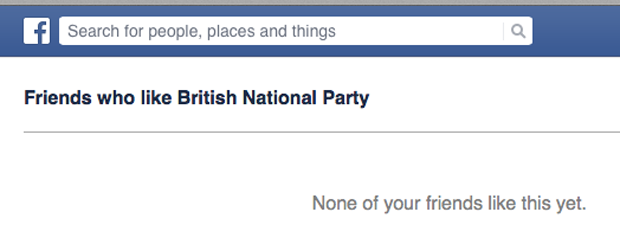

Twitter trolls, online mobs and “offensive” Facebook posts are constantly making headlines as authorities struggle to determine how to police social media. In a recent development, links posted on Facebook allow users to see which of their friends have “liked” pages, such as those representing Britain First, the British National Party and the English Defence League. When clicking the links, a list appears of friends who have liked the page in question. Many Facebook users have posted the links, with the accompanying message stating their intention to delete any friends found on the lists. One user wrote, “I don’t want to be friends, even Facebook friends, with people who support fascist political parties, so this is just a quick message to give you a chance to unlike the Britain First page before I un-friend you.” Tackling racism is admirable, but when the method is blackmail and intimidation, who is in the wrong? All information posted on Facebook could be considered as public property, but what are the ethical implications of users taking it upon themselves to police the online activity of their peers? When social media users group together to participate in online vigilantism, what implications are there for freedom of expression?

This online mob is exercising its right to freedom of expression by airing views about right wing groups. However, in an attempt to tackle social issues head on, the distributors of these links are unlikely to change radical right-wing ideologies, and more likely to prohibit right-wing sympathisers from speaking freely about their views. In exerting their right to free speech, mobs are at risk of restricting that of others. The opinions of those who feel targeted by online mobs won’t go away, but their voice will. The fear of losing friends or being labelled a racist backs them into a corner, where they are forced to act in a particular way, creating a culture of self-censorship. Contrary to the combating of social issues, silencing opinion is more likely to exacerbate the problem. If people don’t speak freely, how can anyone challenge extreme views? By threatening to remove friends or to expose far right persuasions, are the online vigilantes really tackling social issues, or are they just shutting down discussions by holding friendships to ransom?

Public shaming is no new tactic, but its online use has gone viral. Used as a weapon to enforce ideologies, online witch-hunts punish those who don’t behave as others would want them to. Making people accountable for their online presence, lynch mobs target individuals and shame them into changing their behaviour. The question is whether groups are revealing social injustices that would otherwise go unpunished, or whether they are using bullying tactics in a dictatorial fashion. The intentions of the mob in question are good; to combat racism. But does that make their methods justifiable? These groups often promote a “with us or against us” attitude; if you don’t follow these links and delete your racist friends, you must be a racist too. Naming and shaming those who don’t follow the cultural norm is also intended to dissuade others from participating in similar activities. Does forcing people into acting a certain way actually generate any real change, or is it simply an act of censorship?

With online mobs often taking on the roles of judge, jury and executioner, the moral implications of their activities are questionable. It may start as a seemingly small Facebook campaign such as this one, but what else could stem from that? One Facebook user commented, “Are you making an effort to silence your Facebook friends who are to the right of centre?” This concern that the target may become anyone with an alternative political view demonstrates the cumulative nature of online mobs. Who polices this activity and who decides when it has gone too far?

Comments under the Facebook posts in question invite plenty of support for the deletion of any friends who “like” far right groups, but very rarely does anyone question the ethics of this approach. No longer feeling they have to idly stand by, Facebook users may feel they can make an impact through strength in numbers and a very public forum. Do those who haven’t previously had a channel for tackling social issues suddenly feel they have a public voice? Sometimes it’s difficult to accept that absolutely everyone has the right to free speech, even those who hold extreme views. In a democracy, there may be political groups that offend us, but those groups still have a right to be heard. The route to tackling those views can’t be to silence them, but to encourage discussion.

This article was posted on July 9, 2014 at indexoncensorship.org