Index relies entirely on the support of donors and readers to do its work.

Help us keep amplifying censored voices today.

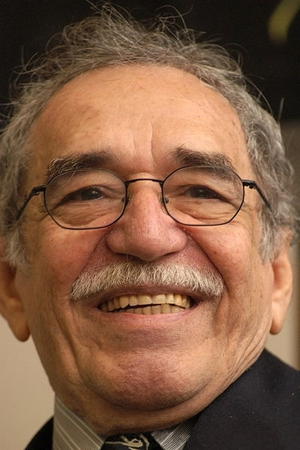

Colombian writer Gabriel García Márquez, who died on 17 April, wrote this piece on the evolution of journalism for Index on Censorship magazine in 1997. Before gaining worldwide acclaim for novels including One Hundred Years of Solitude and Love in the Time of Cholera, Márquez was a journalist for newspapers in Colombia and Venezuela. This piece shares his love of the profession and his concern that reporters have become “lost in labyrinth of technology madly rushing the profession into the future without any control”

Colombian writer Gabriel García Márquez, who died on 17 April, wrote this piece on the evolution of journalism for Index on Censorship magazine in 1997. Before gaining worldwide acclaim for novels including One Hundred Years of Solitude and Love in the Time of Cholera, Márquez was a journalist for newspapers in Colombia and Venezuela. This piece shares his love of the profession and his concern that reporters have become “lost in labyrinth of technology madly rushing the profession into the future without any control”

Some 50 years ago, there were no schools of journalism. One learned the trade in the newsroom, in the print shops, in the local cafe and in Friday-night hangouts. The entire newspaper was a factory where journalists were made and the news was printed without quibbles. We journalists always hung together, we had a life in common and were so passionate about our work that we didn’t talk about anything else. The work promoted strong friendships among the group, which left little room for a personal life.There were no scheduled editorial meetings, but every afternoon at 5pm, the entire newspaper met for an unofficial coffee break somewhere in the newsroom, and took a breather from the daily tensions. It was an open discussion where we reviewed the hot themes of the day in each section of the newspaper and gave the final touches to the next day’s edition.

The newspaper was then divided into three large departments: news, features and editorial. The most prestigious and sensitive was the editorial department; a reporter was at the bottom of the heap, somewhere between an intern and a gopher. Time and the profession itself has proved that the nerve centre of journalism functions the other way. At the age of 19 I began a career as an editorial writer and slowly climbed the career ladder through hard work to the top position of cub reporter.

Then came schools of journalism and the arrival of technology. The graduates from the former arrived with little knowledge of grammar and syntax, difficulty in understanding concepts of any complexity and a dangerous misunderstanding of the profession in which the importance of a “scoop” at any price overrode all ethical considerations.

The profession, it seems, did not evolve as quickly as its instruments of work. Journalists were lost in a labyrinth of technology madly rushing the profession into the future without any control. In other words: the newspaper business has involved itself in furious competition for material modernisation, leaving behind the training of its foot soldiers, the reporters, and abandoning the old mechanisms of participation that strengthened the professional spirit. Newsrooms have become a sceptic laboratories for solitary travellers, where it seems easier to communicate with extraterrestrial phenomena than with readers’ hearts. The dehumanisation is galloping.

Before the teletype and the telex were invented, a man with a vocation for martyrdom would monitor the radio, capturing from the air the news of the world from what seemed little more than extraterrestrial whistles. A well-informed writer would piece the fragments together, adding background and other relevant details as if reconstructing the skeleton of a dinosaur from a single vertebra. Only editorialising was forbidden, because that was the sacred right of the newspaper’s publisher, whose editorials, everyone assumed, were written by him, even if they weren’t, and were always written in impenetrable and labyrinthine prose, which, so history relates, were then unravelled by the publisher’s personal typesetter often hired for that express purpose.

Today fact and opinion have become entangled: there is comment in news reporting; the editorial is enriched with facts. The end product is none the better for it and never before has the profession been more dangerous. Unwitting or deliberate mistakes, malign manipulations and poisonous distortions can turn a news item into a dangerous weapon.

Quotes from “informed sources” or “government officials” who ask to remain anonymous, or by observers who know everything and whom nobody knows, cover up all manner of violations that go unpunished.But the guilty party holds on to his right not to reveal his source, without asking himself whether he is a gullible tool of the source,manipulated into passing on the information in the form chosen by his source. I believe bad journalists cherish their source as their own life – especially if it is an official source – endow it with a mythical quality, protect it, nurture it and ultimately develop a dangerous complicity with it that leads them to reject the need for a second source.

At the risk of becoming anecdotal, I believe that another guilty party in this drama is the tape recorder. Before it was invented, the job was done well with only three elements ofwork: the notebook,foolproof ethics and a pair of ears with which we reporters listened to what the sources were telling us. The professional and ethical manual for the tape recorder has not been invented yet. Somebody needs to teach young reporters that the recorder is not a substitute for the memory, but a simple evolved version of the serviceable, old-fashioned notebook.

The tape recorder listens, repeats – like a digital parrot – but it does not think; it is loyal, but it does not have a heart; and, in the end, the literal version it will have captured will never be as trustworthy as that kept by the journalist who pays attention to the real words of the interlocutor and, at the same time, evaluates and qualifies them from his knowledge and experience.

The tape recorder is entirely to blame for the undue importance now attached to the interview. Given the nature of radio and television, it is only to be expected that it became their mainstay. Now even the print media seems to share the erroneous idea that the voice of truth is not that of the journalist but of the interviewee. Maybe the solution is to return to the lowly little notebook so the journalist can edit intelligently as he listens, and relegate the tape recorder to its real role as invaluable witness.

It is some comfort to believe that ethical transgressions and other problems that degrade and embarrass today’s journalism are not always the result of immorality, but also stem from the lack of professional skill. Perhaps the misfortune of schools of journalism is that while they do teach some useful tricks of the trade, they teach little about the profession itself. Any training in schools of journalism must be based on three fundamental principles: first and foremost, there must be aptitude and talent; then the knowledge that “investigative” journalism is not something special, but that all journalism must, by definition, be investigative; and, third, the awareness that ethics are not merely an occasional condition of the trade, but an integral part, as essentially a part of each other as the buzz and the horsefly.

The final objective of any journalism school should, nevertheless, be to return to basic training on the job and to restore journalism to its original public service function; to reinvent those passionate daily 5pm informal coffee-break seminars of the old newspaper office.

Index on Censorship magazine is proud to have had Gabriel García Marquez among its contributors – a long list which has also included Samuel Beckett, Chinua Achebe, Salman Rushdie and many other literary greats. Printed quarterly, the magazine mixes long-form journalism with short stories and extracts from plays – some of which have been banned or censored around the world. Subscribe here

Gujarat Chief Minister and BJP prime ministerial candidate Narendra Modi filed his nomination papers from Vadodara Lok Sabha seat amid tight security on April 6. (Photo: Nisarg Lakhmani / Demotix)

Electioneering for the Indian elections of 2014 has reached a fever pitch. Never before in the history of modern India has it seemed likely that the country is ready to cut its cord with the Congress Party’s Gandhi family, and never before has its chief opposition party, the Bharatiya Janta Party (BJP) been projected as the sole inheritance of one man – Narendra Modi.

The “greatest show on Earth” – the Indian elections – is underway. There are 37 days of polling across 9 states, with a 814 million strong electorate, and more than 500 political parties to choose from. The hoardings all seem to scream the “development” agenda, but unfortunately in India, this conversation seems to be skating on thin ice. Cracks quickly appear, and beneath the surface, political parties seem to be indulging in the same hate speech, communal politicking and calculations that work to polarise the electorate and garner votes.

Hate speech in India is monitored by a number of laws in India. These are under the Indian Penal Code (Sections 153[A], Section 153[B], Section 295, Section 295A, Section 298, Section 505[1], Section 505 [2]), the Code of Criminal Procedure (Section 95) and Representation of the People Act (Section 123[A], Section 123[B]). The Constitution of India itself guarantees freedom of expression, but with reasonable restricts. At the same time, in response to a Public Interest Litigation by an NGO looking to curtail hate speech in India, the Court ruled that it cannot “curtail fundamental rights of people. It is a precious rights guaranteed by Constitution… We are 128 million people and there would be 128 million views.” Reflecting this thought further, a recent ruling by the Supreme Court of India, the bench declared that the “lack of prosecution for hate speeches was not because the existing laws did not possess sufficient provisions; instead, it was due to lack of enforcement.” In fact, the Supreme Court of India has directed the Law Commission to look into the matter of hate speech — often with communal undertones — made by political parties in India. The court is looking for guidelines to prevent provocative statements.

Unenviably, it is the job of India’s Election Commission to ensure that during the elections, the campaigning adheres to a strict Model Code of Conduct. Unsurprisingly, the first point in the EC’s rules (Model Code of Conduct) is: “No party or candidate shall include in any activity which may aggravate existing differences or create mutual hatred or cause tension between different castes and communities, religious or linguistic.” The third point states that “There shall be no appeal to caste or communal feelings for securing votes. Mosques, churches, temples or other places of worship shall not be used as forum for election propaganda.”

This election season, the EC has armed itself to take on the menace of hate speeches. It has directed all its state chief electoral officers to closely monitor campaigns on a daily basis that include video recording of all campaigns. Only with factual evidence in hand can any official file a First Information Report (FIR), and a copy of the Model Code of Conduct is given along with all written permissions to hold rallies and public meetings.

As a result, many leaders have been censured by the EC for their alleged hate speeches during the campaign. The BJP’s Amit Shah was briefly banned by the EC for his campaign speech in the riot affected state of Uttar Pradesh, that, Shah had said that the general election, especially in western UP, “is one of honour, it is an opportunity to take revenge and to teach a lesson to people who have committed injustice”. He has apologized for his comments. Azam Khan, a leader from the Samajwadi Party, was banned from public rallies by the EC after he insinuated in a campaign speech that the 1999 Kargil War with Pakistan had been won by India on account of Muslim soldiers in the Army. The EC called both these speeches, “highly provocative (speeches) which have the impact of aggravating existing differences or create mutual hatred between different communities.”

Other politicians have jumped on the bandwagon as well. Most recently, the Vishwa Hindu Parishad’s Praveen Togadia has been reported as making a speech targeting Muslims who have bought properties in Hindu neighborhoods. “If he does not relent, go with stones, tyres and tomatoes to his office. There is nothing wrong in it… I have done it in the past and Muslims have lost both property and money,” he has said. There was the case of Imran Masood of the Congress who threatened to “chop into pieces” BJP Prime Ministerial candidate Narendra Modi – a remark that forced Congress’s senior leader Rahul Gandhi to cancel his rally in the same area following the controversy that erupted. Then there is Modi-supporter Giriraj Singh who has said that “people opposed to Modi will be driven out of India and they should go to Pakistan.” In South India, Telangana Rashtra Samithi (TRS) president K Chandrasekhar Rao termed both TDP and YSR Congress (YSRCP) as ‘Andhra parties’ and urged the people of Telangana to shunt them out of the region. The Election Commission has directed district officials to present the video footage of his speeches at public meetings, in order to determine punishment, if needed. Karnataka Chief Minister Siddaramaiah has been served notice by the EC for calling Narendra Modi a “mass murderer”; a reference to his alleged role in the Gujarat riots of 2002.

Shekhar Gupta, editor of the national paper, the Indian Express has published a piece ominously titled “Secularism is Dead,” but instead appeals to the reader to have faith in Indian democracy far beyond what some petty communal politicians might allow. The fact that the BJP’s Prime Ministerial candidate is inextricability linked in public consciousness to communal riots in his home state of Gujarat has only compounded speeches over and above what people believe is the communal politics of the BJP that stands for the Hindu majority of India. In contrast, many believe that by playing to minority politics, the Congress indulges in a different kind of communal politics. And then there are countless regional parties, creating constituencies along various caste and regional fissures.

However, perhaps the last word can be given to commentator Pratap Bhanu Mehta who writes of the Indian election: “But what is it about the structures of our thinking about communalism that 60 years after Independence, we seem to be revisiting the same questions over and over again? Is there some deeper phenomenon that the BJP-Congress system seems two sides of the same coin to so many, even on this issue? The point is not about the political equivalence of two political parties. People will make up their own minds. But is there something about the way we have conceptualised the problem of majority and minority, trapped in compulsory identities, that makes communalism the inevitable result?”

It is this inevitability of communal diatribe, of the lowest common denominators in politics that Indian politics need to rise above. This is being done, one comment at a time, as long as the Election Commission is watching. The bigger challenge lies beyond the results of 16 May, 2014.

This article was posted on 22 April 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

In 2013, by way of abundant caution, Harper Collins India decided to pixellate a total of nine panels, including all the close-ups of penises in David Brown’s graphic novel “Paying for It.” While the content, in which Brown narrated his encounters with sex-workers, was left untouched, the publishers were wary of India’s laws against obscenity which make the depiction of nudity almost verboten. This is because a sheet of prudery covers any sexual expression and also governs the legal regulation of sexual speech.

Hence, many welcomed the Indian Supreme Court’s February 2014 ruling that merely because a picture showed nudity, it wouldn’t be caught within the obscenity net- “a picture can be deemed obscene only if it is lascivious, appeals to prurient interests and tends to deprave and corrupt those likely to read, see or hear it,” and having a redeeming social value would save it from being censored.

The decision came in an appeal filed in 1993. Sports World, a magazine published from Calcutta, had reproduced the photo on the cover of German magazine Stern. In that photograph, Boris Becker had posed nude with his then fiancée Barbara Feltus; it was his way of protesting against the racist abuse the couple were being subjected to. A solicitous lawyer dragged Sports World to court, alleging that the morals of society and young, impressionable minds were in jeopardy. He cited Section 292 of the Indian Penal Code which prohibits and penalises any form of expression tending towards prurience and encouraging depravity in the readers or viewers. The court rejected the contention, holding that the Hicklin’s Test for determining obscenity has become obsolete, besides imposing unreasonable fetters on the freedom of expression. This test, formulated by the House of Lords in 1868 in Regina v. Hicklin stipulated that ‘‘The test of obscenity is whether the tendency of the matter charged as obscenity is to deprave and corrupt those whose minds are open to such immoral influences and into whose hands a publication of this sort may fall.’’

Instead, the United States Supreme Court’s ruling in Roth – wherein “contemporary community standards” were held to be a far more reasonable arbiter, was directed to be adopted. The court also affirmatively cited the decision in Butler which, while upholding the test in Roth, added that anything which showed undue exploitation of sex or degrading treatment of women would remain prohibited.

While the Hicklin’s Test being jettisoned is a cause of relief, the judgement by no means can be held as finally freeing Indian law from the shackles of “comstockery.” George Bernard Shaw had coined this term in 1905 while raging against Anthony Comstock who had taken it upon himself to rid American society of vice. For Comstock, lust and sexual desire were abhorrent, and as he candidly proclaimed anything which even remotely arouses any sexual desire was to be dealt with in the most stringent manner. No wonder he had called Shaw an “Irish smut-peddler” in retaliation.

Gymnophobia, or the fear of nudity, isn’t something new to India’s Supreme Court. Also, it has always been female nudity and the fear of sexual desire which have governed the Court’s opinions. Its image-blaming position has repeatedly been used to reinforce the assumption that sexually explicit images trigger urges in men for which they cannot be held responsible. Depictions of nudity WERE condoned only if they achieved some “laudable social purpose” such as encouraging family planning or making people aware of caste-based atrocities. As Martha Nussbaum points out, collapsing the “disgust” for the nude female body with male sexual arousal and regarding sex as something furtive and impure results in the revulsion being projected on to the female body, thereby making the legal definition of obscenity collude with misogyny.

The present decision is no different. Because Feltus’ breasts were covered by Becker’s arm, and also because Feltus’ father was the photographer, it was held that only the most depraved mind would be aroused and titillated by the magazine cover. Most troubling of all is the overt reliance on contemporary community standards. True, that Indian society has evolved since 1993, but as Brenda Cossman details the scene in Canada in Butler’s aftermath, community standards became a rubric for majoritarian sexual hegemony, resulting in persecution and censorship by prudish vigilantes. And of course, it goes without saying that the search for “redeeming social value” usually ends at puritans’ doorsteps.

Comstockery’s tattered banner, emblazoned with “Morals, not art!” flies aflutter in India.

This article was posted on 22 April 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

Like many other musicians in Mali, Tinawiren were forced into exile by a blanket ban on all music (including mobile ringtones) introduced when hard line Islamists took control of the country in 2012. Tensions continue and award-winning Johanna Schwartz has been capturing this tale in her latest documentary ‘They Will Have To Kill Us First’.

Join us for a preview of this documentary and schedules permitting, a live link up with Manny Ansar – director of the Festival au Desert and central in making the situation for musicians in Mali known to the world.

Subsequently, we’ll explore artistic freedom from a global and local standpoint with renowned writer and broadcaster Kenan Malik, Belfast based international artist Sinead O’Donnell (just back from China) and Julia Farrington of Index.

When: Saturday 3rd may, 15:30-17:00

Where: Belfast Exposed, Donegall St – part of Cathedral Quarter Arts Festival

Tickets: Free – Reserve Your Place Here

#CQAF14