Index relies entirely on the support of donors and readers to do its work.

Help us keep amplifying censored voices today.

(Shutterstock)

James Brokenshire was giving an interview to the Financial Times last month about his role in the government’s online counter-extremism programme. Ministers are trying to figure out how to block content that’s illegal in the UK but hosted overseas. For a while the interview stayed on course. There was “more work to do” negotiating with internet service providers (ISPs), he said. And then, quite suddenly, he let the cat out the bag. The internet firms would have to deal with “material that may not be illegal but certainly is unsavoury”, he said.

And there it was. The sneaking suspicion of free thinkers was confirmed. The government was no longer restricting itself to censoring web content which was illegal. It was going to start censoring content which it simply didn’t like.

If you call the Home Office they will not tell you what Brokenshire meant. Does it mean “unsavoury” material will be forced onto ISP’s filtering software? They won’t say. Very probably they do not know.

There is a lack of understanding at the Home Office of what they are trying to achieve, of how one might do so, and, more fundamentally, of whether one should be trying at all.

This confusion – more of a catastrophe of muddled thinking than a conspiracy – is concealed behind a double-locked system preventing any information getting out about the censorship programme.

It is a mixture of intellectual inadequacy, populist hysteria, technological ignorance and plain old state secrets. And it could become a significant threat to free speech online.

The Home Office’s current over-excitement stems from its victory over the ISPs last year.

Ministers, from New Labour onward, have always tried to bully ISPs with legislation if they refuse to sign up to ‘voluntary agreements’. It rarely worked.

But David Cameron positioned himself differently, by starting up an anti-porn crusade. It was an extremely effective manouvre. ISPs now suddenly faced the prospect of being made to look like apologists for the sexualisation of childhood.

Or at least, that’s how it was sold. By the time Cameron had done a couple of breakfast shows, the precise subject of discussion was becoming difficult to establish. Was this about child abuse content? Or rape porn? Or ‘normal’ porn? It was increasingly hard to tell.

His technological understanding was little better. Experts warned that the filtering software was simply not at the level needed for it fulfill politicians’ requirements.

It’s an old problem, which goes back to the early days of computing: how do you get a machine to think like a person? A human can tell the difference between images of child abuse and the website of child support group Childline. But it has proved impossible, thus far, to teach a machine about context. To filters, they are identical.

MPs like filtering software because it seems like a simple solution to a complex problem. It is simple. So simple it does not exist. Once the filters went live at the start of the year, an entirely predictable series of disasters took place.

The filters went well beyond what Cameron had been talking about. Suddenly, sexual health sites had been blocked, as had domestic violence support sites, gay and lesbian sites, eating disorder sites, alcohol and smoking sites, ‘web forums’ and, most baffling of all, ‘esoteric material’. Childline, Refuge, Stonewall and the Samaritans were blocked, as was the site of Claire Perry, the Tory MP who led the call for the opt-in filtering. The software was unable to distinguish between her description of what children should be protected from and the things themselves.

At the same time, the filtering software was failing to get at the sites it was supposed to be targeting. Under-blocking was at somewhere between 5% and 35%.

Children who were supposed to be protected from pornography were now being denied advice about sexual health. People trying to escape abuse were prevented from accessing websites which could offer support.

And something else curious was happening too: A reactionary view of human sexuality was taking over. Websites which dealt with breast feeding or fine art were being blocked. The male eye was winning: impressing the sense that the only function for the naked female body was sexual.

It was a staggering failure. But Downing Street was pleased with itself, it had won. The ISPs had surrendered. The Washington Post described it as “some of the strictest curbs on pornography in the Western world” – music to Cameron’s ears. Suddenly the terms of the debate started shifting. Dido Harding, the chief executive of TalkTalk, was saying the internet needed a “social and moral framework”.

So instead of proving the death knell for government-mandated internet censorship, the opt-in system became a precursor for a more extensive ambition: banning extremism.

If targeting porn without also blocking sexual health websites was hard, countering terrorism was even more difficult. After all, the line between legitimate political debate and inciting terrorism is blurred and subjective. And that’s not even to address other pieces of problematic legislation, such as the Racial and Religious Hatred Act 2006, which bans incitement to hatred against religions.

Even trying to block what everyone agrees is extremist content is highly controversial. Anti-extremism group Quilliam and security experts at the Royal United Services Institute have warned that closing websites were people are liable to being radicalised actually hinders intelligence services.

A lot of what we know about Brits going off to fight in Syria or elsewhere comes from the fact they write it on message boards. Blocking them just reduces your ‘intelligence take’. Groups like Quilliam also use those sites to go in and engage with people, offering them a ‘counter-narrative’. Blocking the sites prevents them doing their work.

The Home Office mulled whether to add extremism – and Brokenshire’s “unsavoury content” – to something called the Internet Watch Foundation (IWF) list.

The list was supposed to be a collection of child abuse sites, which were automatically blocked via a system called Cleanfeed. But soon, criminally obscene material was added to it – a famously difficult benchmark to demonstrate in law. Then, in 2011, the Motion Picture Association started court proceedings to add a site indexing downloads of copyrighted material.

There are no safeguards to stop the list being extended to include other types of sites.

This is not an ideal system. For a start, it involves blocking material which has not been found illegal in a court of law. The Crown Prosecution Service is tasked with saying whether a site reaches the criminal threshold. This is like coming to a ruling before the start of a trial. The CPS is not an arbiter of whether something is illegal. It is an arbiter, and not always a very good one, of whether there is a realistic chance of conviction.

As the IWF admits on its website, it is looking for potentially criminal activity – content can only be confirmed to be criminal by a court of law. This is the hinterland of legality, the grey area where momentum and secrecy count for more than a judge’s ruling.

There may have been court supervision in putting in place the blocking process itself but it is not present for individual cases. Record companies are requesting sites be taken down and it is happening. The sites are only being notified afterwards, are only able to make representations afterwards. The tradional course of justice has been turned on its head.

The possibilities for mission creep are extensive. In 2008, the IWF’s director of communications claimed the organisation is opposed to censorship of legal content, but just days earlier it had blacklisting a Wikipedia article covering the Scorpions’ 1976 album Virgin Killer and an image of its original LP cover art.

Sources close to the ISPs say they were asked to take the IWF list wholesale – including pages banned due to extremism – and block them for all their customers, whether they had signed into the filtering option or not.

They’ve proved commendably reluctant, although their reticence is as much about legal challenges as a principled stance on free speech. Regardless, they seem to be insisting that universal blocking can only be carried out with a court order. Brokenshire is then left trying to get them to include it in their optional, opt-in filter.

We don’t know if he’s succeeded in that. The Home Office are resistant to giving out any information. They direct inquiries to the Department of Culture, Media and Sport or ISPs themselves, who really have no idea what’s going on. They refuse to answer any questions on Cleanfeed, saying it is a privately owned service – a fact which is technically true and entirely misleading.

It is not conspiracy. It is plain old cock up, combined with an inadequate understanding of the proper limit of their powers.

The left hand does not know what the right hand is doing. Even inside departments of the Home Office they do not know what they are trying to achieve.

The policy formation is weak and closed. The industry is not in the loop. Media inquiries are being dismissed. The technological understanding is startlingly naive.

The prospect of a clamp down on dissent is real. It would come slowly, incrementally – a cack-handed government response to technological change it does not understand.

We must be grateful for James Brokenshire. His slip ups are the best source of information we have.

This article was originally posted on 17 April 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

Umida Akhmedova took part in a small protest in Tashkent, in solidarity with the Euromaidan movement.

On 27 January, internationally renowned photographer Umida Akhmedova, her son Timur Karpov and seven other people took to the streets of Tashkent, Uzbekistan. Armed with Ukrainian flags, cameras and a petition, they staged a peaceful protest in solidarity with the Euromaidan movement.

Knowing they might attract unwanted attention, the group, which included one journalist reporting, posed for a few photos outside the Ukrainian embassy, handed over the petition, and quickly wrapped up the demonstration. However, their worries soon proved valid. Three days later, the protesters were hauled in one by one by police for a “short talk”. They would be held incommunicado for one day, first in a central Tashkent police station and later at a more remote location.

Karpov, a photographer based in Russia, told Index about unprofessional and aggressive officers, who called the protesters “dissidents” who were “ruining the constitution”. Passports and phones were taken away, but Karpov managed to keep one concealed to alert the outside world to their detention. It was eventually discovered and confiscated. When he got it back, it had been completely wiped. Without access to lawyers, the protesters were questioned by the SNB — the KGB’s successor — before being put through a quickie court session and ordered to pay fines of some £1,200. Three of them have been sentenced to 15 days in prison. Justice, as understood by Uzbekistan’s notoriously repressive regime.

This is not the first time Akhmedova has run into trouble with the regime of former Communist Party official Islam Karimov. In 2009, the photographer and documentary film maker, whose work has been published in The New York Times and Wall Street Journal, was charged with “damaging the country’s image” over a series of photographs depicting life in rural Uzbekistan. Similar charges were later levelled at her over a film about challenges facing Uzbek women, and in 2010, over a book about Uzbek traditions. It’s worth noting that she never intended to make a political statement with her work — the authorities’ reaction is what has politicised it. The cases have made Akhmedova a credible voice of opposition, and while her high profile provides some protection, it also means her every move is noted — as the latest case shows.

“We live in a strict, archaic society, where all unregulated acts, especially those that can cause some kind of a response in the society, are nipped in the bud,” she told Index. “In the case of our Maidan project, the authorities did not have to be clairvoyants to see the similarities between the situation in Ukraine and the one in Uzbekistan. The government has started scaring children and adults with the word Maidan and did not like it when we showed support for Maidan.”

“As for our previous case,” she adds “we were charged with slander and insult of Uzbek nation, because the government wanted to teach us a lesson that without the approval from above, we were not allowed to film anything or publish books, or generally, do anything artistic without a superior permission.”

While Akhmedova’s latest arrest hit headlines across Central Asia, the story made little impact in the west. This is not surprising. Earlier this year the soap opera-like falling out between first daughter Gulnara Karimova — businesswoman, sometimes pop star, and until recently tipped to follow in her father’s presidential footsteps — and, seemingly, the rest of the family was covered by media outside the country. But on the whole, Uzbekistan rarely commands international attention. Like many other countries in the region, it is able to carry out its repressive rule away from the global spotlight.

President Karimov, by taking a number of liberties with the country’s constitution and term limits, has been in power since it gained independence from the Soviet Union in 1991. Reports of torture and other power abuses are widespread, the darkest days of the regime coming with the Andijan massacre, where security forces killed hundreds of people in the aftermath of a peaceful protest. The country is also one of the most corrupt in the world and despite its gas resources — part of the reason for many western sanctions quietly being dropped — suffers “recurring energy crises“. But Karimov has been careful to remove nearly all institutions that might use this information to challenge his power. Uzbekistan has no official opposition parties and no press freedom to speak of. Opposition news sites that operate outside of the country are blocked. Karpov puts it simply: “There is no freedom of expression in Uzbekistan. Absolutely none.”

One aspect of the widespread press censorship, is that developments in Ukraine have been met with near media blackout in Uzbekistan — the same way authorities dealt with the Arab spring and other incidents of popular unrest outside the country’s borders.

“From my point of view, they’re afraid. Extremely afraid of any sort of freedom,” says Karpov. ” That’s why they made the case with us. To frighten us. To show to other people that if you do this, you will be sentenced.”

Mother and son have accepted their punishment — partly because refusal to do so would lead to further blacklisting, and partly because they weren’t alerted to their appeal until after it had taken place. Unsurprisingly, the sentences were not overturned.

Despite this latest setback, and the possibility of being handed down a travel ban, Akhmedova remains undeterred. “Nothing has changed for me. I will carry on ‘slandering’ as I have done,” she says. “The state cannot help or stop me.”

This article was originally posted on 17 April 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

I was retweeted by Caitlin Moran on Wednesday evening (#humblebrag). It was a curious glimpse into the world of internet fame. Suddenly my replies were full of retweets and favourites – hundreds of them.

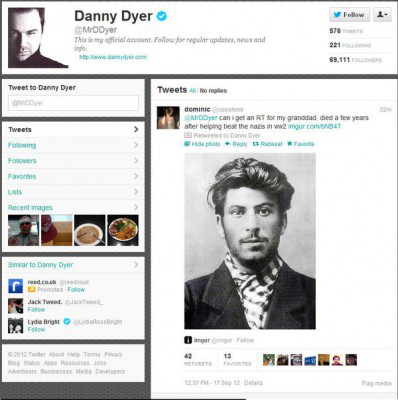

The tweet itself was fairly innocuous; in fact, it was a bit of a cheat. I’d copied someone else’s tweet, adding my own disbelief. And that tweet by someone else was a retweet of a three-year old tweet by well-hard actor Danny Dyer, who had been tricked, quite amusingly, by someone asking for a shout out to his grandad who had helped beat the Nazis, accompanied by a picture of a young Stalin. I’d missed it at the time.

Anyway, on it came throughout the evening, retweets, favourites, questions, statements of the obvious, snark…. It was weird, and unexpected, and kind of exciting. It was like I’d done something really good, rather than just stealing someone else’s old joke. And I was able to track exactly how good it was. I had pulled some kind of killer move and was getting my reward. I was winning the game.

In his 2013 documentary on video games that changed the world, Charlie Brooker, who knows so much about these things, caused a small stir when he suggested that Twitter was in essence, an online multiplayer game. Considering how high-mindedly people like me talk about social media as platforms for change, tools of democratisation and so on, it’s a provocative view to take. But Brooker is right. Twitter users are engaged in a massive game, possibly without end. We measure the success of individual moves (tweets) with retweets and favourites: keep pulling off these successful moves, and we can see our scores go up, in terms of followers accumulated. Not counting the uber famous, who will get a million retweets for the most grudgingly given “I HEART MY FANS; here’s the merchandise page” tweet, most of us are in this game to some extent.

But the description of Twitter as a game has one problem: Twitter can have real-life consequences.

Periodically (well, every time Grand Theft Auto comes out), Keith Vaz or Susan Greenfield or someone will get terribly upset about the ruination caused to young minds or young morals by all this mindless violence. This game lets you steal cars! Run down old ladies! All sorts of unspeakable things! But GTA and other games let you do nothing of the sort: at best, they let you pretend you’re doing these things. In fact, it’s not even that: it lets you control a character, whose character is already somewhat predetermined, in doing some of these things. You’re essentially engaged in a technologically advanced form of improv theatre. Except far more entertaining.

And this is where the Twitter-as-game thing falters: if I threaten to blow up a plane while playing a normal video game, nothing will happen to me. If I do it on Twitter, well…

Last Sunday a 14-year-old Dutch girl called Sarah got in trouble for tweeting that she was a member of Al Qaeda and was about to do “something big” to an American Airlines flight.

According to Dutch news agency BNO, the exchange went as follows:

“Hello my name’s Ibrahim and I’m from Afghanistan. I’m part of Al Qaida and on June 1st I’m gonna do something really big bye,” the girl, identifying herself only as Sarah, said in Sunday’s tweet. Soon after, American Airlines responded in their own tweet: “Sarah, we take these threats very seriously. Your IP address and details will be forwarded to security and the FBI.”

“omfg I was kidding. … I’m so sorry I’m scared now … I was joking and it was my friend not me, take her IP address not mine. … I was kidding pls don’t I’m just a girl pls … and I’m not from Afghanistan,” the girl said in subsequent tweets, later adding: “I’m just a fangirl pls I don’t have evil thoughts and plus I’m a white girl.”

It’s a stupid thing to do, obviously. But Sarah was playing by the rules of the game. She was being provocative, and, in her mind at least, funny. These are things that get you RTs and followers.

But sadly for Sarah, and the rest of us, there comes a point where social media stops being a game and starts being serious business.

We’ve seen this in the UK, of course, with Paul Chambers and the infamous Twitter Joke Trial.

That entire case was a travesty, because no one at any point believed Chambers even meant to behave threateningly. It’s unlikely anyone really believes Sarah meant anything by her tweet either, but in the order of things so far established, directing a comment at an account (at-ing someone, for want of a better phrase), as the Dutch girl did, is worse than simply referring to them, as Chambers did in his tweet about blowing Doncaster’s Robin Hood airport “sky high”.

Where is all this going to end up? I really don’t know. But I can only reiterate the point made many times before that, intriguingly, with the increasing ease of free speech, we’re seeing the rise of an increasing urge to censor; not just in authorities, but in everyday people.

It’s an urge we have to resist.

This article was originally published on 17 April 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

The campaign against Senegalese artists and celebrities who are often paid thousands of pounds for praise singing Gambia’s authoritarian government, has in recent months intensified.

Awarding winning singer and music producer Youssou N’Dour in late March signed a controversial deal with the Gambia Social Security and Housing Finance Cooperation worth 3 million dalasi (£45118.82) to stage a three day concert in the capital Banjul beginning on 18 April. In response, the Democratic Union of Gambian Activists (DUGA) has written an open letter to N’Dour and the artists he produces, imploring them to be sensitive to “the plight and suffering of Gambians, especially journalists” in their dealings with the regime of President Yahya Jammeh.

N’Dour responded to the letter by saying he did not want to deprive his Gambian brothers and sisters of the cultural exchanges. However, DUGA pointed out that in 2003, the singer boycotted the United States in protest of the invasion of Iraq, depriving his music from his brothers and sisters living in the USA. “In your own words you said ‘I believe that coming to America at this time would be perceived in many parts of the world rightly or wrongly as support of this policy’,” the group quoted N’Dour as saying in the open letter posted on Facebook.

DUGA said the artist’s work with Human Rights Now, Amnesty International, Band Aid and numerous other causes has made him a giant on the world stage in the fight against injustice and poverty around the globe, adding that the entire world listened to his inspirational song in support of Nelson Mandela.

The activists urged the singer not to forget Gambians in his humanitarian activities: “In 2012 your principle fight against a third term of the former president of Senegal, you did not hesitate to say No!, and demanded that democracy must be the rule of the continent. On numerous occasions, you have persistently denounced what is seen as flagrant violation of the fundamental human rights. Mr N’Dour’s song New Africa has been a source of inspiration and strength for many Gambians in the struggle to free our country from one of the most authoritarian regimes in the world today.”

DUGA pointed out that while “Gambia may not have declared war on another nation and the streets may not be littered with bodies”, Gambians are not living in peace. They cited human rights violations against journalists, opposition politicians and regular people, including judicial harassment, torture, violence and extended detention without trial, and also mentioned the many Gambians forced into exile out of fear for their lives.

The letter added that “not participating in shows initiated for or by Jammeh will be a show of support for numerous Gambians in their fight against tyranny, while equally paying homage to Senegalese who have died under inhumane conditions in the Gambia, notably, Tabara Samb, Gibril Ba, Ousmane Sembene; and the countless and nameless others in Cassamance who have died as a direct consequence of the rebellion perpetuated by President Jammeh.”

Ibou N’Dour, Youssou N’Dour’s brother, told Jollofnews in response to the DUGA letter that they are not politicians, and will play for any politician provided that they sign a contract. “We will play a paid concert for Yahya Jammeh, you cannot wait for musicians to solve political problems”, he stressed.

In February the Democratic Union of Gambian Activists and Senegal’s “Fed Up” (Y’en a Marre) movement launched a campaign in Dakar targeting musicians including Ousman Diallo alias Ouza, Kumba Gawlo Seck, Thione Seck and Assan Ndiaye, and Senegalese wrestler Oumar Saho alias Bala Gaye, for praise singing and carrying out promotional activities for Jammeh.

Ouza Diallo, a Senegalese artist seen as a revolutionary due to the significant role he played in effecting democratic change in Senegal during the 2000 and 2012 presidential elections, has denied being a praise singer for the regime in Banjul. He has accused the rights activist of being manipulated by the west, and recently described the Gambian dictator as a true Pan-African.

But while some support the campaign against Senegalese artists, an observer who wished to remain anonymous denounced it, adding that musicians have a right sing for anyone that can pay them money. She said that the activists should support the Gambian people by implementing projects to create employment and empower them rather than “abusing the rights of musicians, who are only doing their job as entertainers”.

This article was posted on 17 April 2014 at indexoncensorship.org