Index relies entirely on the support of donors and readers to do its work.

Help us keep amplifying censored voices today.

(Image: Aleksandar Mijatovic/Shutterstock)

As states have been revealed to be snooping on citizens and other governments, and we are confronted by data breaches and security issues like the latest Heartbleed crisis, more people are becoming aware of their internet rights. Voters and civil society around the world are pushing their governments to provide secure and private online spaces for internet users. It is quite refreshing to see Pakistan’s government working for internet laws. However, though some provisions of the proposed Computer Crimes Law (CCL) are copied from other countries’ legislation, several parts of the draft version violate international human rights, including the freedom of expression.

In an attempt to offer support to the government of Pakistan, Article 19 and Digital Rights Foundation Pakistan dissected the draft legislation to point out the provisions that need to be amended, and to help the government conform to international human rights norms. It is mandatory at this point to pressure the government to put in place better internet legislation in order to avoid future misuse of the legal framework, as has happened with other laws.

A leading example of how such poorly devised laws help authorities abuse power is the Monitoring and Reconciliation of International Telephone Traffic Regulations (MRITT), also known as the Grey Traffic legislation. Passed in 2010 to help the government ban anonymous communication and VPN usage, MRITT mandates the monitoring and blocking of any encrypted and unencrypted traffic that originates or terminates in Pakistan, including phone calls and data.

MRITT legitimised blocking and internet monitoring on a massive scale — allowing a ban on VPN and VoIP services like Skype, Viber, WhatsApp and SpotFlux among others. The implementation of this legislation raises several concerns especially among the business community of Pakistan. The first official notification citing the MRITT to block VPN was issued in July 2011, targeting “all mechanisms which conceal communication to the extent that prohibits monitoring”.

The global reliance on the internet for communications and the, at times, complete blackouts of certain services by the government of Pakistan pose serious economic challenges. Not only business, but educational activities are hampered by the implications of MRITT. It also affects the privacy rights of Pakistani citizens. License deploying monitoring systems are expected to provide data — including a complete list of Pakistani consumers and their details — to the authorities when required under sub clause 6(d) of Part II of the regulation.

The Pakistan Protection Amendment Bill 2014 is another scary example of a woolly worded law. It was recently passed by Pakistan’s national assembly and is awaiting approval by the senate. Human Rights Watch stated that: “The vague definition of terrorist acts, which could be used to prosecute a very wide range of conduct — far beyond the limits of what can reasonably be considered terrorist activity. Besides ‘killing, kidnapping, extortion,’ the law classifies highly ambiguous acts including ‘Internet offences’ and ‘disrupting mass transport systems,’ as prosecutable crimes without providing specific definitions for such offences.”

The latest version of the Computer Crimes Law has been drafted by the Ministry of Information Technology and Telecommunications (MoITT). The proposed law establishes various computer crimes and sets out rules for investigation, prosecution and trial of these offences. Acts such as illegal access to and interference with programs, data or information systems; cyber terrorism; electronic forgery and fraud; making of devices for use in these types of offences; and unauthorised interception of communication are included. Like MRITT, it is feared that the Computer Crimes Law in its current draft form, if passed, would include several violations to the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), to which Pakistan acceded in 2010.

The concerns over the Computer Crimes legislation mentioned by Article 19 and Digital Rights Foundation, include lack of proper definitions of terms like content, data, information system or program. Their recommendations also highlight concerns about broader cyber-terrorism offences under Section 7 (a) and (b), and more importantly, the lack of procedural safeguards against unchecked surveillance activities carried out by the country’s intelligence agencies.

At this stage of the process, it is important for regional and international civil society and internet privacy rights groups to put pressure on the government of Pakistan to make the right amendments to the law before passing it. This law is extremely important for providing safety and security to Pakistani internet users and cannot be abolished or delayed. It is only right, then, that it introduces correct and clearly defined provisions to make it effective, and not vulnerable to abuse by authorities.

This article was published on 17 April 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

Greek protesters voiced their opposition to further austerity measures on Wednesday 9 April as Greece returned to international finance markets. (Photo: Christos Syllas for Index on Censorship)In a televised address last Thursday, Greek Prime Minister Antonis Samaras thanked the Greek people for the sacrifices they endured during the past four years as the country underwent the harshest austerity measures since emerging from World War II. While hailing the country’s return to the international finance markets after a four-year absence, the prime minister and the coalition government glossed over policies that have resulted in a negative environment for free expression — whether through protests or the press.

Along with the “world of labor” being constantly undervalued, the policies put in place are having a huge impact on the freedom of speech. In a more precise manner, the non-dominant anti-state and anti-government political discourse produced by certain political spaces such as the radical left and anarchists poses a serious threat to the government propaganda. Political dissidents are being targeted, arrested and systematically abused for protesting against the government. At the same time, press freedom is under attack when attempting to speak about the costly agreements with the troika. Also, recent struggles for education came face to face with police interference and student profiling.

The economic implications of the Greek austerity drive are falling mostly on the working class, who are losing hard won benefits without their unions taking a clear stand against the rollbacks. The government is currently legislating a new round of liberalization measures.

On 9 April, an anti-austerity strike was held in Athens with thousands of people rallying against government policies. Although the strike lacked the mass participation and intensity of past rallies, as in 2012, demonstrators managed to manifest their dissent against sweeping socio-econonic measures.

According to the latest data from the Hellenic Statistical Authority, Greece’s unemployment in January 2014 was 26.7%, up from 26.5% a year ago and down from 27.2% in December. The same figure back in January 2009 was at 8.9%. The economic downfall can be clearly seen at the unemployment rate among 15-24 years old and 25-34 years old: 56.8% and 35.5% respectively.

Workfare policies through voucher programmes, initially introduced as a government solution to unemployment, exploit the large reserve of unemployed while undermining the ability to collectively bargain working conditions and pay.

“It is a dead end. If you take a closer look today -a day of strike-, you will see that many coffee shops and sales shops are open. Austerity measures, up to now, seem to be effective in dividing working class people and overturn any social struggle. There’s still a long way to fight properly…”, a 29 year-old protester, who has been unemployed for two years, told Index on Censorship.

Human rights abuses against immigrant workers — the most undervalued part of workforce in Greece — confirm the agenda of a police state flirting with racism and xenophobia.

The dramatic escalation of refugee and migrants’ mistreatment, both by the state and the banned neo fascist party Golden Dawn is indicative. In a recent provocation some Golden Dawn followers organized an intimidating gathering outside the offices of Medecins du Monde, an NGO that provides medication and healthcare services to immigrants as well as Greeks.

However, mainstream media outlets have failed to report on the contradictions that arise from Golden Dawn’s background and relationships. Index on Censorship has thoroughly reported on the affinities of the right and the far-right political spectrum and has identified some key actors that connected ruling party New Democracy with Golden Dawn. One of them, was the former cabinet secretary Panayiotis Baltakos.

Baltakos was recently forced to resign over a leaked video, which showed him having a conversation with the spokesman of Golden Dawn Ilias Kasidiaris. In the video, Baltakos admitted that the government had to press judges to prosecute Golden Dawn’s former members of parliament.

It is worth noting that a year ago, Baltakos had allegedly said that cooperation between New Democracy and Golden Dawn in upcoming elections is “undesirable but not an unlikely possibility”.

The continuous flirting between the ruling New Deomocracy and the now-banned Golden Dawn either takes the form of a “relationship” or of a “conflict”. It is shaping the news agenda and it sets the tone ahead of the European and local elections in May.

In an e-mail interview that took place in January, Index asked Cas Mudde, assistant professor in the Department of International Relations at the University of Georgia, in whose interest is the threat of the far-right is working.

“I would expect that the far right today wins mostly from mainstream right-wing parties – in many countries they won over the left-wing voters in the late-1980s/early-1990s. At the same time, they often attract many new and former non-voters, who would probably traditionally have gone to the center-left”.

Mudde also claims, among other things, “that European politicians use the alleged threat of a far right resurgence, backed by the economic crisis thesis, to push through illiberal policies”.

In this context, on 11 April, German Chancellor Angela Merkel visited Athens. Aside from the mainstream media’s enthusiasm for the return to financial markets, few read between the lines. Merkel’s visit was a sign of support for the Greek government’s austerity measures – despite what the Greek public thinks

Experts warn that even now that “the mood has changed”, the debt crisis and the consequent austerity measures do not necessarily come to an end.

This article was published on 16 April 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

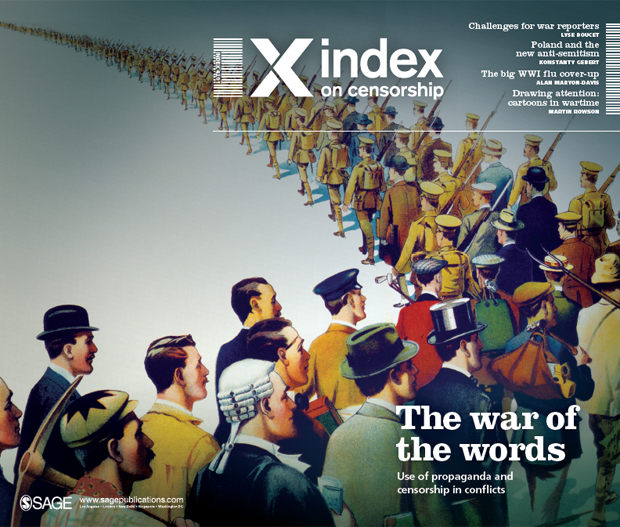

Join us at the Hay Festival to debate what happens to the truth during wars and conflicts. Where is the line between national security and public information? Is it ever right not to tell the whole truth?

These issues are discussed in the latest Index on Censorship magazine, looking back to World War I, and bringing the debate up to date with discussions on war reporting in Syria and Afghanistan today.

This Index on Censorship magazine platform at Hay features David Aaronovitch (columnist/broadcaster and Index chair), Alan Maryon-Davis (writer/broadcaster and doctor), Leanne Green (Imperial War Museum) and is chaired by Rachael Jolley (editor, Index on Censorship magazine).

WAR AND PROPAGANDA launches the Spring edition of Index on Censorship magazine with its special report on the use of propaganda and censorship during conflicts, marking the centenary of the beginning of World War I. Each attendee will receive a free copy of the magazine.

When: Sunday 25th May, 7:00pm

Where: Llwyfan Cymru – Wales Stage, Hay Festival

Tickets: Reserve your tickets (public booking opens Wednesday 9th April, 10pm)

The Hindu Janajagruti Samiti’s (HJS) unmistakable glee knew no bounds. It had scored a hat trick of getting Ali J, a play centred around the partition of India and communal riots, and seeking to demolish every argument advanced by Hindu fundamentalists, off the stage.

First it was Mumbai, when on 6 February the organisers of the prestigious Kala Ghoda Festival, fearing violence from HJS and political party Shiv Sena, were cowed into calling it off. On March 9, the Chennai Police, citing “law and order problems” asked the troupe to cancel the show. And on 12 March, an hour before the play was about to start, Bangalore cops barged into the theatre and told the performers to clear off from the premises.

The memorandum submitted by the HJS, a revanchist organisation dedicated to “rekindling righteousness” and reawakening (Janajagruti means “mass awakening” in Sanskrit) Indians’ pride in their ancient culture, reads like a study in jingoism laced with vicious communalism. Evam, the Chennai-based theatre group producing the play, is accused of hurting religious sentiments and assaulting nationalistic pride because, among other things it shows an inter-faith love affair, depicts the persecution of Muslims, advocates jihad, depicts Jinnah as being a taller personality than Gandhi, and overall militates “against the established moral principles of Indian society”. These bellicose claims must be greeted with incredulity because as Karthik Kumar, the director and lead actor asserts in an interview to a national daily, none of these purveyors of “Indian morality” had even watched the play. Moreover, as Kumar categorically says, the crux of Ali J’s message was to recall the horrors of partition and caution against the purveyors of hate who indulge in polarising people on the grounds of religion.

This spate of censorious incidents leads one to a number of questions. What is the provenance of organisations like the HJS and the Shiv Sena? What motivates them to claim a sole monopoly on the interpretation of history? And, does the state bear no responsibility in thwarting their efforts?

The systematic rewriting of history and imposing myths upon established facts is a critical component of the Hindu nationalist ideology, for, the doctrine of Hindutva mandates not an India of cultural and ethnic syncretism, but a “Hindustan” in which rabid Islamophobia runs riot. It isn’t the first time that the depiction of partition — the goriest and most viciously communal episode in South Asian history — has been attacked by Hindu supremacists.

In April 1974, M.S. Sathyu’s film Garam Hawa (Hot Wind) — the heartrending tale of the “scorching, simmering and debilitating winds of communalism, political bigotry and intolerance” incurred the Shiv Sena’s wrath. Salim Mirza, the protagonist, was a study in resilience and religious tolerance. Even when everything around him is charred in the communal inferno, he refused to leave India. Bal Thackeray, the Shiv Sena supremo, was so enraged at this humanistic portrayal of a Muslim that he threatened to raze to ashes every single theatre and screen which showed the film. The premiere at Bombay’s Regal Cinema was stalled because the police played mute bystanders. Only after a special screening was hastily arranged for Thackeray and he was satisfied that a Muslim had to stay back and join the Indian (read “Hindu”) mainstream was the film allowed to go on.

Tamas, a television serial carrying pretty much the same message as Garam Hawa, encountered similar opposition in 1988. It didn’t help that the government of Maharashtra, citing possible law and order problems, effectively played tango with the champions of censorship. It could go on air only after the Supreme Court rejected the government’s apprehensions as unfounded.

It would indeed be short-sighted to reserve trenchant criticism only for the bullies who squelch freedom of expression, for more often than not, the government is equally complicit. This is because India’s constitution is unequivocal — that restrictions on speech can be imposed only if “public order” and not the “law and order situation” is in jeopardy. Last year, the Tamil Nadu government took this specious and patently illegal plea while stalling Vishwaroopam, a film which some Muslim organisations found offensive. The courts have clearly stated that “law and order” was narrower in scope than “public order”, and these two should not be interpreted interchangeably, and it is incumbent upon the state to protect the fundamental right to speech in the face of onslaughts.

As long as the government pussyfoots or plays a charade for purposes of political expediency, the HJS and others of its ilk will be thirsting for more glory.

This article was published on April 16, 2014 at indexoncensorship.org