Index relies entirely on the support of donors and readers to do its work.

Help us keep amplifying censored voices today.

Brazilian President Dilma Rouseff spoke at the opening of NETmundial.

“In 2013, the revelations about the comprehensive mechanisms for spying and monitoring communications provoked outrage and disgust in broad sectors of the Brazilian and the world’s public opinion. Brazilian citizens, companies, embassies and even the President of the Republic had their communications intercepted. Such facts are unacceptable. They undermine the very nature of the Internet: open, pluralistic and free”.

With these words, President Dilma Rousseff opened the NETmundial – Global Multistakeholder Meeting on the Future of Internet Governance, held in São Paulo on April 23 and 24.

Organized by the Brazilian Internet Steering Committee (CGI.br) and /1Net, the unprecedented gathering brought together 1,229 participants from 97 countries. The meeting included representatives of governments, the private sector, civil society, the technical community and academics. Among those present were the Under Secretary-General of the United Nations, Wu Hongbo; the President of ICANN (Internet Corporation for Assigned Names and Numbers), Fadi Chehade; the “father” of the Web, Tim Berners-Lee, and the co-author of TCP/IP and vice-president of Google, Vint Cerfol. The creator of WikiLeaks, Julian Assange, attended the event via Skype.

The words of the president of Brazil seemed to indicate the tone of the meeting: “This reunion responds to a global desire for change in the current situation, with the systematic strengthening of freedom of expression on the internet and the protection of basic human rights, such as the right to privacy”.

In the audience, activists wore masks with the face of Edward Snowden, whose leaks were a catalyst for NETmundial. They protested against the Article 15 of the Marco Civil–signed into law by Rousseff at the event’s opening ceremony–which orders the retention of users’ browsing data. Some demanded that Brazil offer asylum to Snowden.

The main objective of NETmundial was to begin to formulate a system of international internet governance that will come into effect in September 2015, when the United States steps away from the coordination of ICANN, which administers and manages the names and domains used on the internet.

NetMundial was born thanks U.S. spying that targeted the Brazilian government. Rousseff personally stitched together the event after her speech at the UN General Assembly last year that strongly condemned the NSA spying.

After the meeting, a statement of principles was approved. However, the document does not clearly state any principle governing the massive data espionage or violation of privacy. The term “neutrality” appears only in the list of topics to be discussed in the future. The mass surveillance is identified only as a discrediting factor of the net: “Mass and arbitrary surveillance weakens the trust and the confidence in the internet and in the ecosystem of internet governance”, says the document. The collection and use of personal data “should be subject to international human rights law”. And nothing more. Without incrimination, without any preventive or corrective measure, the question remained open. The postponement of the discussion about net neutrality was advocated by the U.S. private sector.

The final document raised much criticism from civil society, which had their expectations disappointed. With a weak text, the Charter of Principles was more like a set of corporate standards, with little affirmative language, full of marketing buzzwords. Its statements are soft. The governments’ voices, especially the U.S.’s, sounded much stronger. Civil society condemned the lack of explicit rules for the “net neutrality” – the term, by the way, was not even mentioned. Another criticized point was the inclusion of protection and copyright of intellectual property, which meets to the interests of lobbyists from business environment and is contrary to the recommendations of collaborative and free creation.

“The document ended up not reflecting the greatness of the debate that happened here. We missed the chance to produce a substantial document to the discussion of the internet governance”, said Laura Tresca, from the NGO Article 19. “The positive balance is in the process, which was interesting: we experienced the idea of the multistakeholder model in practice; but the final document was too weak.”

EFF published a text that defined the outcome of the meeting as “disappointing”.

The multistakeholder model was criticized by activists as “oppressive, determined by political and market interests”. People like Jérémie Zimmermann (La Quadrature Du Net, which defends the rights and freedom of citizens on the web) and Jacob Appelbaum (developer and security researcher) said that the principles of NetMundial were “empty of content and devoid of real power”. These activists argue that governments have an obligation to ensure the rights of users and that the internet is a common, free and geared to citizens’ good.

It would be very difficult to have unanimity with so many sectors present. Russia, Cuba and India disagreed with the Charter of Principles. Brazil’s minister of communications, Paulo Bernardo, missed a more forceful condemnation of espionage. “For obvious reasons, the United States was uncomfortable with it”, said Bernardo. He recognized that the document is not perfect, but evaluates that it means a victory for the future of governance. The idea now is to enhance the text in other debates, such as the Internet Governance Forum (IGF), that will be held next September in Turkey and in Brazil in 2015.

NETmundial was a historic step putting Brazil in the frontline for internet use in the world, even with the disagreements and a questionable model. Nevertheless, it lacked the courage to allow the voice of the people to sound louder than economic interests. To push the most important issues into the future for further discussions was a mistake – both strategic and purposeful. In this sense, they have bitten more than they could chew.

A previous version of this article referred to Wu Hungbo as the Secretary-General of the United Nations. His correct title is Under Secretary-General of the United Nations. This has now been corrected.

This article was published on April 30, 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

VIENNA, April 30, 2014 – The European Commission’s support for projects addressing violations of media freedom and pluralism, and providing practical support to journalists, gives European Union countries reason to celebrate this year on May 3, World Press Freedom Day, media freedom watchdogs said today.

However, new research into defamation law and practice – one of four, one-year projects launched in February under a Commission-funded grant programme focusing on the 28 EU member and five candidate countries – has shed light on one big elephant in the room, the Vienna-based International Press Institute (IPI) said. Preliminary results of a study by IPI and the Center for Media and Communications Studies (CMCS) at Budapest’s Central European University reveal that criminal laws in the EU addressing libel, slander, and insult remain rife and, in many cases, contravene international and European standards.

Furthermore, as another project, “Safety Net for European Journalists”, registered, attacks on journalists continue to represent a major challenge to press freedom in Europe. Research and field work by the Osservatorio Balcani e Caucaso, IPI affiliate the South East Europe Media Organisation (SEEMO), Ossigeno per l’Informazione and Dr. Eugenia Siapera of Dublin City University have shown that journalists across Southeast Europe, Turkey and Italy often face common threats and pressure, highlighting a crucial need for transnational support.

“Media freedom and pluralism can unfortunately not be taken for granted in Europe,” Neelie Kroes, vice-president of the European Commission responsible for the Digital Agenda, said. “We all, governments, NGOs, the media, and the EU institutions have a role to play in standing firmly to defend these principles, in Europe and beyond, now and tomorrow, on and off-line. I am interested to see what the outcome of the independent projects will be.”

The European Commission grant programme, the “European Centre for Press and Media Freedom”, is funding two projects in addition to IPI’s project researching the effects of defamation laws on journalism in Europe and raising awareness of the same, and the “Safety Net” project establishing a transnational support network for journalists in Southeast Europe, Turkey and Italy. Index on Censorship has created a project to map media freedom violations, and the Florence-based Centre for Media Pluralism and Media Freedom (CMPF), also working in conjunction with CMCS, is creating tools and networks to strengthen journalism in Europe.

The grantees’ work, combating violations of the fundamental right to press and media freedom, is intended to play a critical role in protecting both the fundamental human right of free expression, as guaranteed by Article 11 of the EU’s Charter of Fundamental Rights, as well as the media’s instrumental role in safeguarding democratic order.

Some of the grantees will also collaborate to establish an intra-European network of legal assistance for media outlets facing legal proceedings.

IPI and CMCS plan to launch a comprehensive report in early June on the status of criminal and civil defamation law in EU member and candidate countries, intended to help identify states where engagement is required most urgently. The report will evaluate each country across a number of categories, including the types of defences and punishments available and the existence of provisions shielding public officials, heads of state, or national symbols from criticism. It will also include a first-of-its-kind “perception index” to gauge the subjective effect that criminal and civil defamation proceedings have on press freedom.

Preliminary research shows that, in nearly all EU member states, libel and insult remain criminal offences punishable with imprisonment – up to five years in some cases – and that journalists continue to face prosecutions in numerous countries, particularly Croatia, Greece, Hungary, Italy, Malta and Portugal. While some countries have seen movement toward decriminalisation, only a small minority of states have fully abolished criminal libel and insult provisions, among them Ireland, Romania and Britain.

A key finding so far is that while national courts in many cases apply European Court of Human Rights precedents on protection of freedom of expression, few EU member states have adopted legislation that meets these standards. This is particularly true with regard to defences available to journalists in libel proceedings. In IPI’s view, the lack of modern legislation clearly establishing defences of truth, public interest, fair comment and honest opinion contributes to an atmosphere of uncertainty and potential self-censorship on matters of public interest.

Additionally, the research so far has shown that legal protections shielding public officials from scrutiny are prevalent in many countries, and that such provisions often are found in tandem with increased punishments for journalists and media outlets that publish content that could be deemed defamatory. The combination of these two instruments – present in the laws of many EU member states – significantly weakens legal safeguards that enable journalists and media outlets to perform their necessary watchdog roles. Such barriers pose undue restrictions on freedom of expression rights and the public’s right to know, as established by international and EU conventions and treaties.

Despite clear challenges, however, the research has also found several important positive movements, including the enactment of modern civil defamation legislation in Ireland in 2009 and in England and Wales in 2013, as well as the full repeal of criminal libel in those jurisdictions. The removal, for the most part, of prison sentences as a punishment for libel in Finland, new discussions among Italian lawmakers to end imprisonment for criminal defamation and the repeal of a French law punishing insults to the president all indicate a growing, if slow, willingness to tackle archaic legislation.

If you would like more information or to schedule an interview with IPI Senior Press Freedom Adviser Steven M. Ellis, please call +43 (1) 512 9011 or email [email protected].

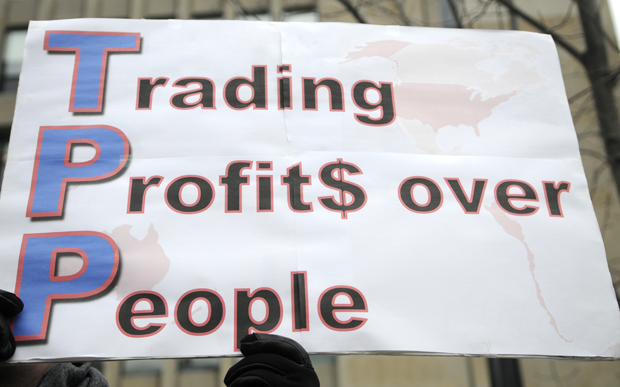

A sign saying “trading profits over people” during a rally to protest the proposed TPP trade agreement and NAFTA Agreement on January 31, 2014 in Toronto, Canada. (Photo: Shutterstock)

As President Barack Obama returns from Asia trade talks today, freedom of speech campaigners plan to deliver nearly three million signatures to the White House, gathered over recent weeks on the Stop The Secrecy website.

Freedom of expression campaigners have warned that the Transpacific Partnership trade agreement, which Obama has been negotiating with a dozen Asian governments, will have wide-reaching censorship implications.

With secret negotiations reportedly at a critical stage, campaigners have mounted a global plan to draw the attention to the role that internet providers would play in preventing the free flow of information.

The draft chapter of the Trans-Pacific Partnership Agreement on Intellectual Property— in its current leaked version mandates signatory governments to provide legal incentives for Internet Service Providers (ISPs) to privately enforce copyright protection rules.

The TPP wants service providers to undertake the financial and administrative burdens of becoming copyright cops, serving what the Electronic Frontier Foundation call “a copyright maximalist agenda”.

The agreement also proposes wide-reaching alterations to the controversial topic of copyright laws, including laws that require ISPs to terminate their users’ Internet access on repeat allegations of copyright infringement, requirements to filter all internet communications for potentially copyright-infringing material, ISP obligations to block access to websites that allegedly infringe or facilitate copyright infringement, efforts to force intermediaries to disclose the identities of their customers to IP rights holders on an allegation of copyright infringement.

While this might be good news for music, film and TV companies – who have seen profits fall off the back of websites such as the Pirate Bay, but a spokesperson for Electronic Frontier Foundation warned the result could be a “cautious and conservative” internet afraid to run into draconian enforcement policies laid out under the new TPP rules.

“Private ISP enforcement of copyright poses a serious threat to free speech on the internet, because it makes offering open platforms for user-generated content economically untenable,” argue EFF.

“For example, on an ad-supported site, the costs of reviewing each post will generally exceed the pennies of revenue one might get from ads. Even obvious fair uses could become too risky to host.”

EFF also warned that ISPs take-down “ask questions later” approach to copyright infringements could give corporations too much power to remove time-sensitive user-generated content, for example a supporting video for an election campaign.

“Expression is often time-sensitive: reacting to recent news or promoting a candidate for election. Online takedown requirements open the door to abuse, allowing the claim of copyright to trump the judicial system, and get immediate removal, before the merits are assessed.”

TPP, which is currently being negotiated between the United States and a dozen major markets in Asia, It is a key plank in Obama’s much feted “pivot to Asia” and could affect up to 60% of American exports and 40% of world trade.

The US-led treaty has proposed criminal sanctions on copyright infringement and – according to EFF – could force internet service providers to monitor and censor content more aggressively, and even block entire websites wholesale if requested by rights holders.

Backed by a number of groups including Avaaz, Reddit, Electronic Frontier Foundation and Open Media International, the anti-TPP coalition is also employing guerrila marketing techniques. These include projecting campaign slogans onto key government buildings in Washington, in an attempt to draw wider attention to the secretive talks, as well as a digital banner that can be easily installed on any website.

The trade negotiations have controversially gone on largely behind closed doors – and while talks are believed to have stalled between Japan and the United States in the latest round – many countries, including Vietnam and Australia, are vociferous advocates.

WikiLeaks’ Julian Assange, who master-minded the release of a rare leaked chapter of the agreement in November, is adamant the deal’s worst aspects lie in its approach to intellectual property.

Speaking when the documents were first published on the Wikileaks website, he observed: “If instituted, the TPP’s IP regime would trample over individual rights and free expression, as well as ride roughshod over the intellectual and creative commons”

He added “If you read, write, publish, think, listen, dance, sing or invent, the TPP has you in its crosshairs.”

OpenMedia’s Executive Director Steve Anderson, told Index “If the TPP’s censorship plan goes through, it will force ISPs to act as “Internet Police” monitoring our internet use, censoring content, and removing whole websites.”

OpenMedia, although based in Canada, has led the charge in co-ordinating the campaign to shed light on censorship aspects of the deal.

“A deal this extreme would never pass with the whole world watching – that’s why U.S. lobbyists and bureaucrats are using these closed-door meetings to try to ram it through. Our projection will shine a light on this secretive and extreme agreement, sending decision-makers a clear message that we expect to take part in decisions that affect our daily lives.”

This article was originally published on April 30, 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

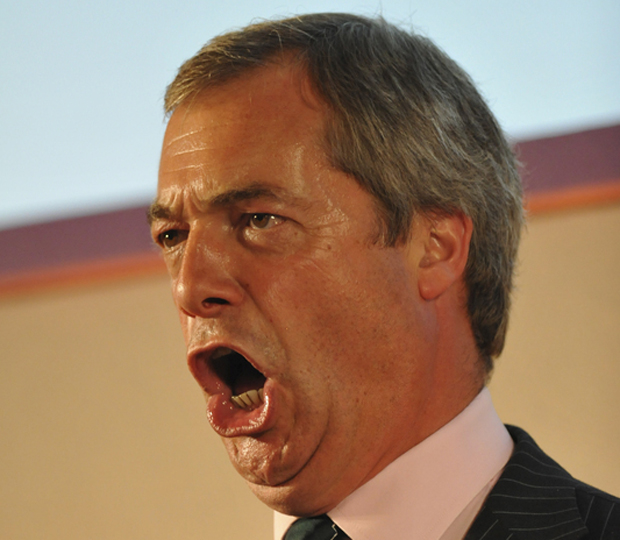

(Photo: Michael Preston / Demotix)

Ofcom’s decision to declare the UK Independence Party a ‘major party’ for the purposes of this month’s European elections has led to questions about who should be allowed to address the public. Behind the scenes, broadcasters have asked why their right to editorial freedom is restricted at all.

UKIP’s leader, Nigel Farage, responded: “This ruling does not cover the local elections, despite UKIP making a major breakthrough in the county elections last year. This strikes me as wrong.”

Natalie Bennett, leader of the Green Party – which Ofcom decided was not a major party – pointed out that, unlike UKIP, her party has an MP, and is also “part of the fourth-largest group in the European Parliament”.

Both sides pounced on the Liberal Democrats, whose dwindling position in the polls, they hinted, should see it demoted to minor party status.

The decision means commercial TV channels that show party election broadcasts must allow UKIP the same number of broadcasts as the Conservatives, Labour and the Liberal Democrats. They will also be given equal weight in relevant news and current affairs programming. However, for content focusing on, or broadcasting solely to, Scotland, UKIP’s lower levels of support there mean it will remain a minor player.

This of course gives UKIP a certain level of legitimacy, and the scope to influence even more voters. For those campaigning against them, the move is grossly unfair.

The Green Party in particular feels hard done by. From the House of Lords to local councils it has representatives at every level, but Ofcom still claims it hasn’t achieved enough. Yet in its report the regulator said that it could not make UKIP a major party in Scotland without granting the same status to the Scottish Green Party, due to their comparable performance.

Ofcom has promised to review the list periodically, so things could change in future. But for now it believes the list represents political realities. UKIP’s focus on getting Britain out of Europe has helped it to do well at the past few European elections. In 2009 it came second in terms of vote share, up from third place in 2004, and this year a number of polls indicate that it could win. In more recent local elections UKIP has done well, achieving 19.9 per cent of the total vote in 2013. But this has leapt up from 4.6 per cent in 2009’s local elections, which for Ofcom is not consistent enough to justify extra coverage for its prospective councillors.

So it seems fair enough that UKIP counts as an important party for Britain in the European Parliament. The Greens are yet to win enough votes in enough elections for their inclusion to make sense. And the Liberal Democrats appear to be clinging on only because of their level of support in past general elections, which was also taken into account.

But the real question is why a list is necessary at all. After all a “regulated free press” sounds something like “freedom in moderation” – ultimately a nonsense. Ofcom’s control over which parties receive coverage puts a dampener on broadcasters’ right to freedom of expression and makes it more difficult for newer parties to break through.

Responding to a previous consultation on whether the list of major parties should be reviewed, Channel 4 said the regulator’s rules should “ensure that political messages are conveyed in a democracy… [but] such regulation should be as narrow as possible to restrict… any interference with the broadcaster’s right to editorial independence and its rights to freedom of expression”. Channel 5, meanwhile, said the concept of major parties did not have “continuing relevance at a time of increasing political flux and fragmentation within the electorate”.

Ofcom appears to be prioritising the need of the electorate to be informed. So it could be argued that, for the purposes of allocating party election broadcasts, the list is useful to prevent any channel from steadfastly omitting information on a party that is likely to appear on most voters’ ballot papers.

But in terms of news and current affairs programming, there seems little reason that broadcasters shouldn’t have the freedom to say what they please – particularly because newspapers are faced with no such restrictions.

As the dominance of mass media fades, and the internet provides access to alternative points of view, the restrictions on the news you receive through your TV will only become more obvious.

This article was originally published on April 30, 2014 at indexoncensorship.org