Rashid Razaq is a reporter for London Evening Standard and a playwright.

What is the solution to the Muslim Problem? Britain has tried multiculturalism; the French, a stricter enforcement of secularism. Neither has been an unequivocal success.

I’m afraid I don’t have the answer. I have only doubts and questions, whereas the terrorists have certainties and guns.

The only thing I can say with a fair amount of confidence is that the right not to be offended is a ridiculous thing. For there is no way to measure a subjective, emotional state other than to ask “Does this offend you?” in the same way you would ask “Are you tired?”, “Are you hungry?”, “Do you love me?”

One person’s silly cartoon is another person’s existential threat. Try as I might, I cannot get offended by a drawing. Maybe I’m a bad Muslim, maybe a true believer would be so mortally wounded by an image, any image, of the Prophet Mohammed that the only remedy is bloodshed. But I don’t think that’s the case. Much of the outrage is manufactured, stoked up by rabble-rousers for political purposes. Because that’s the brilliance of the right not to be offended (Irony — just to be crystal- clear): you can get offended on other people’s behalf, you can get offended about books you haven’t read, about things that may or may not exist.

Loath as I am to bring up scripture in a discussion about religion, the Islamic prohibition against making graven images of the Prophet Mohammed only really applies to Muslims. It stems from the same commandment not to worship false idols, intended to protect against idolatry.

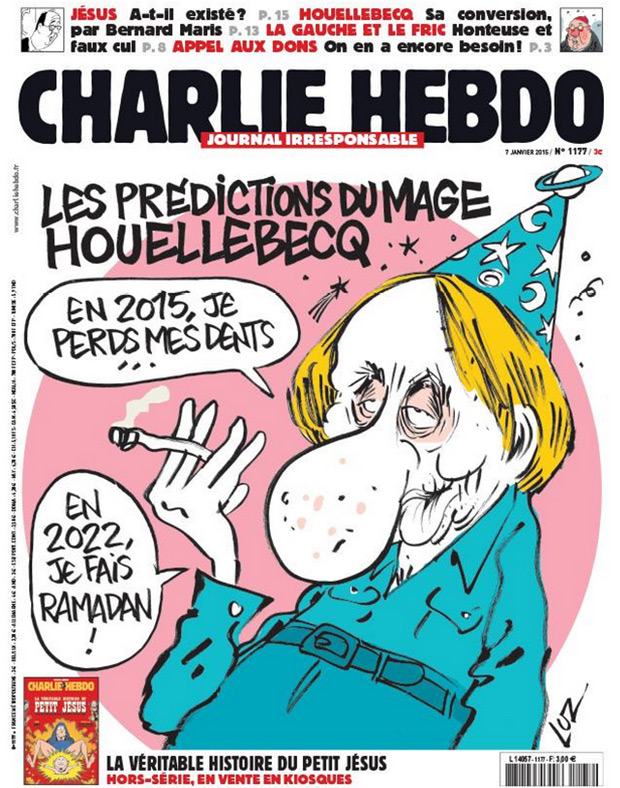

As far as I’m aware neither Stephane Charbonnier nor any of his leading cartoonists at Charlie Hebdo was a practising Muslim. The two victims believed to be Muslims, copy-editor Mustapha Ourad and policeman Ahmed Merabet, appear to have been collateral damage rather than targets.

So, just to make the murders even more pointless, you have Muslims killing non-Muslims for not sufficiently respecting something which they don’t believe in. Irony? I’m not sure.

Not that there is any justification. It is a shabby excuse for a heinous act, convenient religious cover for something that is probably nothing more than a twisted marketing stunt for al Qaeda in Yemen, if initial accounts prove to be true. The killings were not carried out to “avenge” the Prophet’s honour. Their real intent was to remind the West: “We’re still here”.

Many lofty and true words will be written about the need to protect the freedom of expression. But the attack on Charlie Hebdo wasn’t an attack on freedom of expression. It was an attack on an easy target. A group of middle-aged, unarmed cartoonists were never going to be much of a match for battle-hardened jihadists brandishing Kalashnikovs.

Satire is scary for people who can’t live with doubt. Because satire is all about creating doubt, questioning the way things are done, challenging those in power, pushing for change. I don’t know if the killings say more about the power of satire or the weakness of the gunmen’s supposed faith.

The jihadists want us to accept their narrative, that they are brave holy warriors and not just some over-sensitive, bloodthirsty bullies. But I have my doubts. I think the terrorists continue to provoke fear because they’re afraid. Afraid that we’ll realise their brand of religion is a joke.