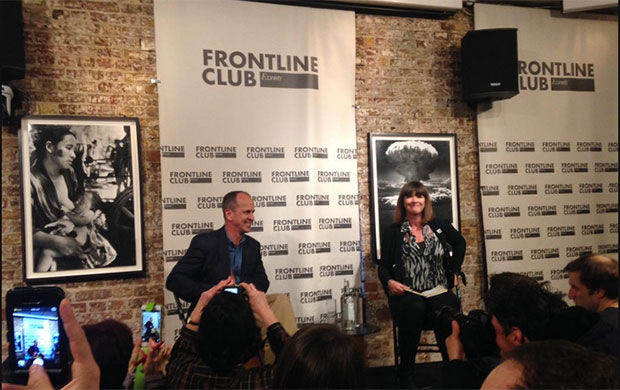

Peter Greste spoke to a Frontline Club audience about his arrest and detention in Egypt. (Photo: Milana Knezevic / Index on Censorship)

Peter Greste, the Al Jazeera journalist recently released after 400 days in Egyptian jail, met a packed room at London’s Frontline Club on Thursday, where he spoke about his time in jail, the campaign for his release and fellow journalists still imprisoned in Egypt. “An attack on journalism, an attack on freedom of speech, is an attack on the wider society,” he said.

“I remember that day well,” he said, recounting 29 December 2013, when a group of around eight men came to his Cairo hotel room and without explanation started searching it, before talking him away. While he was aware that the media was under some pressure in Egypt, the arrest came as a surprise. He felt as long as they stuck to their journalistic principles and didn’t push boundaries, they would be fine.

“There have been plenty of stories before where I’ve pushed boundaries, when I fully expected to get a knock on the door from the police, when I know I’ve upset governments,” he explained. But this time around, he hadn’t gone looking for difficult stories or made a conscious effort to try and challenge the government, so he “genuinely didn’t think it was going to be an issue.”

Greste was imprisoned together with Al Jazeera producer Baher Mohamed and Al Jazeera English’s Cairo bureau chief Mohamed Fahmy. He said they forced themselves to consider that they might be convicted, but never seriously believed it.

While there were “some very dark moments”, he insisted anger wasn’t his dominant emotion, believing that letting anger take hold of the situation would only hurt himself. They were broadly treated with respect in prison, and never physically threatened. “The problem is that in prison…what really matters is your own head, your own mind and how you cope with it.”

Egypt

Index has reported extensively on the situation confronting free expression in the country

Committee to Protect Journalists named Egypt as one of the world’s top 10 jailers of journalists in Dec 2014

Reporters Without Borders: World Press Freedom Index ranks the country as 159

Freedom House: Classifies Egypt as “not free”

Greste spoke of the importance of having a routine and some structure to his day, crediting seemingly simple things like meditation, exercise, studying and even cooking with helping him though the ordeal.

“The only way through is to set your horizon, to set a target date, to set something that’s manageable,” he said. “What you do is narrow your horizon, to the thing that you think you can cope with. Sometimes that was the end of next week, or it would be to the next visit. Sometimes it would be simply to the end of the day.”

Today, he doesn’t feel traumatised, and believes that we are all more capable of dealing with difficult situations than we think. And when discussing the conditions in prison, it was clear he had kept his humour. “The less said about the toilets the better,” he joked.

If his detention had been a surprise, so was his release. He had been expecting his brother for a visit, when he got the unexpected message to pack his bags — he was going home. Himself, Fahmy and Mohamed had discussed the possibility that one of them might be released before the others, and all agreed that if that were to happen, there would be no doubt that that person should go.

And yet, Greste said walking away and leaving Mohamed and others (Fahmy was receiving medical treatment at the time) behind was not easy. “And I still feel that and I still feel quite anguished about it.” His two colleagues have now been released on bail, with their retrial set to start on Monday.

Greste was also keen to remind us that while the three of them had been given the most media attention, many others had been caught up in the case — including three young students, a businessman and journalists sentenced in absentia.

“We can’t forget that sympathy tends to go with people who you identify with. As a European, as a white guy, it’s easier for white Europeans to identify with me than it is to identify with an Egyptian. I’m not suggesting for a second that that makes Baher’s case any less worthy. And in a way we need to bear that in mind, that because of that trend, it’s so easy to let local journalists slip through the cracks,” he also added. “It is the locals that get hit, and the freelancers in particular.”

He said he’ll continue to report, though he is not yet sure what form his work will take. He also hopes to continue to speak out for press freedom.

“One of the most extraordinary elements of this, and one that we are in danger of losing, if we do not make a conscious effort to hold on to, is the unity of purpose that emerged within the media community around our case. For some reason, the community right across the globe pulled together in a way that I think is absolutely unprecedented; we’ve never seen anything like this ever before,” he said.

“If we lose that sense of purpose, then we lose something that we have created of enormous value. I think its very difficult to maintain, particularly under the current circumstances, but I think it’s incumbent on everybody to recognise it, to make use of it, not just in our case but in the case of every journalist that’s been imprisoned.”

This article was posted on 20 February 2015 at indexoncensorship.org