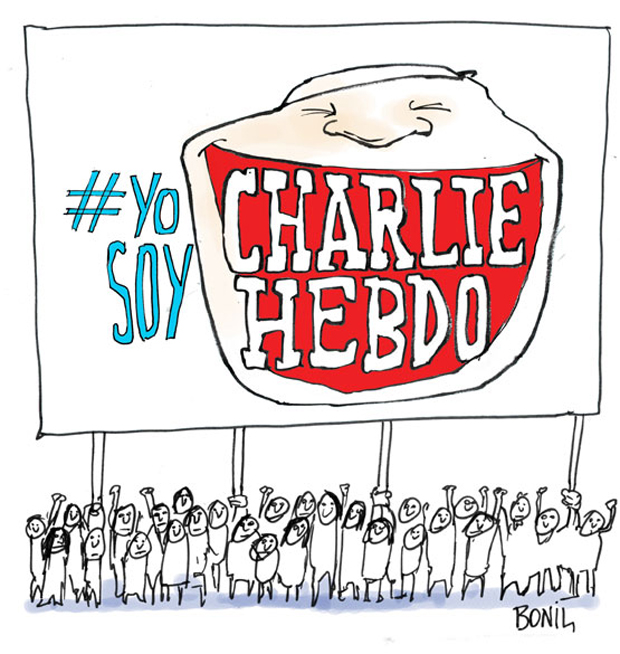

The decision by six authors to withdraw from a PEN American Center gala in which Charlie Hebdo will be honoured with an award once again emphasises the dangerous notion that some forms of free expression are more worthy than others of defending.

Charlie Hebdo was offensive to many — but as PEN points out — it was also vigorous in its defence of the importance of free speech, even in the face of those who would seek to silence that view through violence.

“Free speech for all can only be protected by standing up as vigorously – if not more vigorously – for the views you disagree with as those with which you agree,” said Index CEO Jodie Ginsberg. “If we don’t do that, freedom becomes something only for the favoured and powerful.”

Below Index republishes an article from CEO Jodie Ginsberg written a week after the attacks on Charlie Hebdo that addresses the importance of a defence of free speech in all its forms.

If you said “I believe in free expression, but…” at any point in the past week, then this is for you. If you declared yourself to be “Charlie”, but have ever called for an offensive image to be removed from public viewing, then this is for you. If you “liked” a post this week affirming the importance of free speech, but have ever signed a petition calling for a speaker to be banned, then this is for you.

Because the rush to affirm our belief in free expression in the wake of Charlie Hebdo attacks ignores a simple truth: that free speech is being eroded on all sides, and all sides are responsible. And it needs to stop.

Genuine free expression means being able to articulate thoughts, feelings and ideas without fear of harm. It is vital because without it individuals would be subject to the whim of whichever authority dictated what ideas and opinions – as opposed to actions – are acceptable. And that is always subjective. You need only look at the world leaders at Sunday’s Paris solidarity march to understand that. Attendees included Ali Bongo, President of Gabon, where the government restricts any journalism critical of the authorities; Turkish Prime Minister Ahmet Davutoglu, whose country imprisons more journalists in the world than any other; and the UK’s David Cameron, who declared his support for free expression and the right to offend, while his government considers laws that could drive debate about extremism underground.

It is precisely the freedom for others to say what you may find offensive that protects your own right to express your views: to declare, say, your belief in a God whom others deny exists; or to support a political system that others dismiss. It is what enables scientific and academic thought to progess. As soon as we put qualifications around “acceptable” free expression, we erode its value. Yet that is precisely what happened time and again in response to the Charlie Hebdo attacks, with individuals simultaneously declaring their support for free expression while seeming to suggest that the cartoonists and anyone else who deliberately courts offence should choose other ways to express themselves – suggesting that the responsibility for “better” speech always lies with the person deemed to be causing offence rather than the offended.

“The free communication of ideas and opinions is one of the most precious of the rights of man. Every citizen may, accordingly, speak, write and print with freedom…”

French National Assembly, Declaration of the Rights of Man, August 26, 1789

Index believes that the best way to tackle speech with which you disagree, including the offensive, and the hateful, is through more speech, not less. It is not through laws and petitions that restrict the rights of others to speak. Yet, increasingly, we use our own free speech to call for that of others to be limited: for a misogynist UK comedian to be banned from our screens, or for a UK TV personality to be prosecuted by police for tweeting offensive jokes about ebola, or for a former secretary of state to be prevented from giving an address.

A project mapping media freedom in Europe, launched by Index just over six months ago, shows how journalists are increasingly targeted in this region, including – prior to last week’s incidents – 61 violent attacks against the media. Globally, the space for free expression is shrinking. We need to reverse this trend.

If you genuinely believe in the value of free speech – that all ideas and opinions must be heard – then that necessarily extends to the offensive and the vile. You don’t have to agree with someone, or condone what they are saying, or the manner in which it is said, but you do need to allow them to say it. The American Civil Liberties Union got this right in 1978 when they defended the rights of a pro-Nazi group to march in Chicago, arguing that rights to free expression needed apply to all if they were to apply to any. (As did charity EXIT-Germany late last year, when it raised money for an anti-fascism cause by donating money for every metre walked during a neo-Nazi march).

Countering offensive speech is – of course – only possible if you have the means to do so. Many have observed, rightly, that marginalisation and exclusion from mainstream media denies many people the voice that we would so vociferously defend for a free press. That is a valid argument. But this should be addressed – and must be addressed – by tackling this lack of access, not by shutting down the speech of those deemed to wield power and privilege.

Voltaire has been quoted endlessly in support of free expression, and the right to agree to disagree, but British author Neil Gaiman, who discusses satire and offence in the winter Index magazine, also had it right. “If you accept — and I do — that freedom of speech is important,” he once wrote, “then you are going to have to defend the indefensible. That means you are going to be defending the right of people to read, or to write, or to say, what you don’t say or like or want said…. Because if you don’t stand up for the stuff you don’t like, when they come for the stuff you do like, you’ve already lost.”

This article was originally posted on 12 January 2015 and reposted on 27 April 2015 at indexoncensorship.org